TASSET Jacques (EN)

Biographical Article

Burgundian through his mother, Élisa Euphrasie Maillet (1839-1888), Parisian through his father, the artist and medal engraver Paulin Tasset (1839-1921), Jacques Alphonse Tasset spent the first part of his life in Paris, until 1901, before retiring as a "man of letters" in Molosmes then in Tonnerre, the respective locations of his mother’s death and birth.

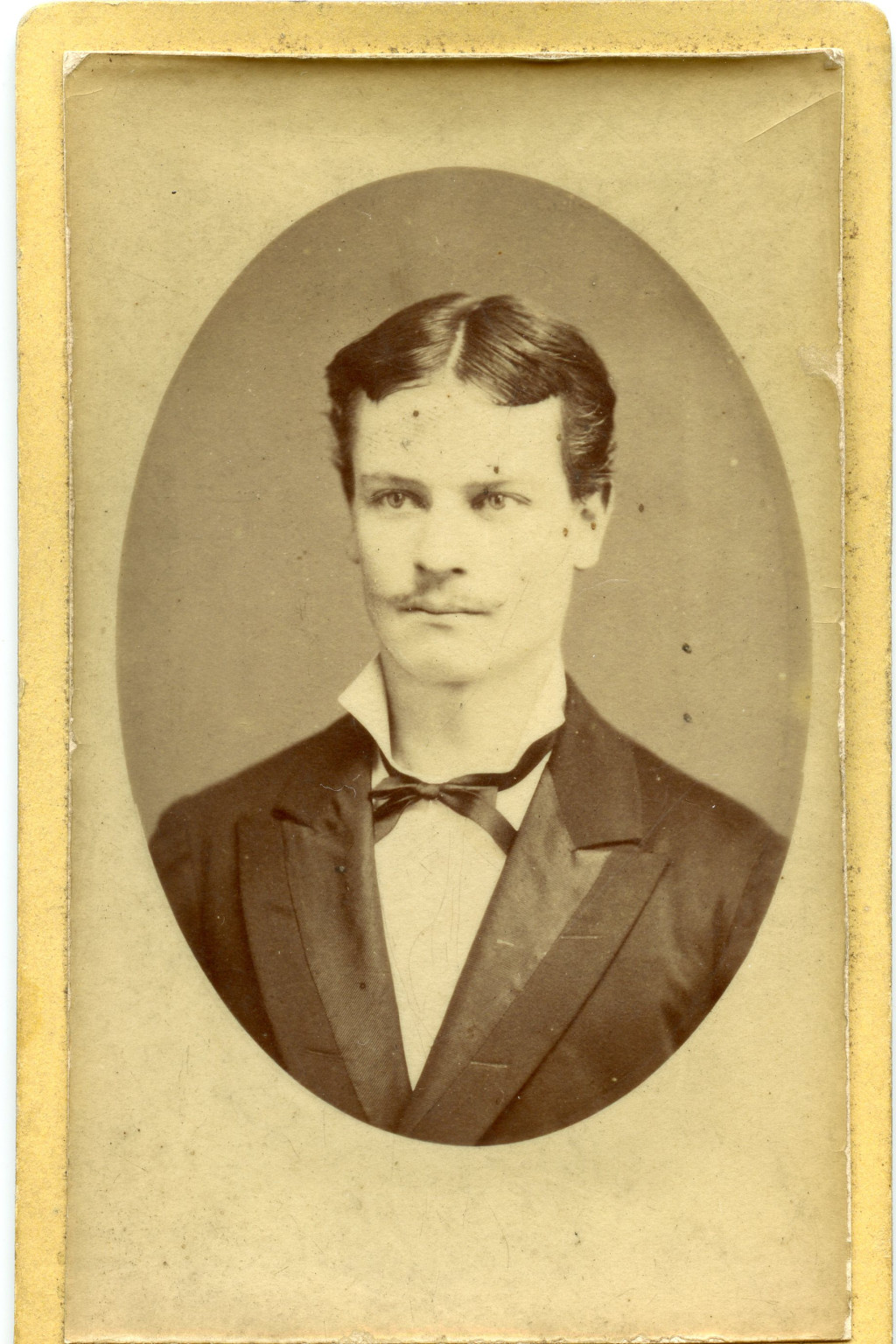

The Parisian period was marked by engagement in not only the ethnographic and orientalist scientific milieu, but also the artistic and spiritual circles. Jacques Tasset obtained his baccalauréat in letters at the Collège Sainte-Barbe on May 24, 1889. It was there that he befriended Émile Bernard (1868-1941) who would become one of the representatives of the Pont Aven group. (Laporte M., 2021). In 1890, Bernard painted the only known portrait of Tasset, apart from a photograph (illustrating this notice) that was recently discovered by Martine Laporte. The painting, dedicated to Tasset, was acquired at auction for 26,880 Euros.

Jacques Tasset then enrolled in the faculty of law from November 1889 to May 1891 and took his last exam in July of that same year (AN, AJ16/21/87). In the same autumn of 1889, Jacques Tasset enrolled at the École des langues orientales in the Japanese course (AN, 62/AJ/23), where Motoyoshi Saizau (元吉清蔵) (1866-1895), editor of the Revue bouddhique du Japon and promoter of jōdo shinshū Buddhism in France (Saizau M., 1891 and Tasset J., […]), officiated as a tutor. He obtained the title of graduate student there in 1893. At the same time, Tasset enrolled in the École Pratique des Hautes Etudes (EPHE) and attended lectures on Chinese, then on religions of the Far East and American Indians, until 1894 (AN, 20190568212). His Orientalist career was entirely under the direction of Professor Léon de Rosny (1837-1914), who had initiated Japanese studies in France in 1863. As part of Rosny's course on the "history of the origins of Taoism" in 1892, Tasset presented a memoir on the religious ideas of the Taiping sect (太平道) (Annuaire de l'École Pratique des Hautes Etudes, year 1892-1893). From the start of his studies at the École des langues orientales, Jacques Tasset joined as an active member the various groups gathered around Rosny in various learned societies and in particular: the Société d’ethnographie, the Sinico-Japanese Committee in 1889 and the Committee of Comparative Religions, the École du bouddhisme éclectique in 1892 (his name appears among the signatories of Lawton F. et al., 1892), and finally in 1896 the Alliance scientifique universelle. Jacques Tasset's meeting with Léon de Rosny probably took place within the family, as Paulin Tasset had been in contact with Léon de Rosny for a long time within the Société d’ethnographie de Paris, which the latter had founded in 1859 (the Société d’ethnographie d’Amérique et orientale became the Société d’ethnographie in 1864). Paulin Tasset had managed the Society's library since 1885, located not far from their home at 28 rue Mazarine. Furthermore, Jacques Tasset's father had since 1884 been a member of the Sinico-Japanese Committee of the Alliance scientifique universelle, an association also founded by Rosny. Finally, we find the name of Paulin Tasset in 1898 in the registers of the EPHE, since he was enrolled in Léon de Rosny’s course on the religions of the Far East that year. In parallel with his studies of Chinese and Japanese, Tasset learned Sanskrit (AN, F/17/3008), either with Sylvain Lévi (1863-1935) at the EPHE who had taken over the teaching of Abel Bergaigne ( 1838-1888) in 1884, or by following the courses of Philippe-Édouard Foucaux (1811-1894), which the latter had given at the Collège de France since 1858.

Either through his association with artistic circles or his career in Asian studies, Jacques Tasset became a member of the Theosophical Society in 1891. Journalists and public opinion at the time assimilated theosophists, whose head office had been established since 1879 in Adyar (on the outskirts of Madras, today Chennai) in India, to "neo-Buddhism" in Europe and even to the vogue of "Parisian Buddhism" which was then emerging (Thévoz S., 2017). The press echoed what it called Jacques Tasset's "conversion to Buddhism" (Le Rappel, June 17, 1891): "Until now, our Parisian neo-Buddhists have stuck to the philosophy of religion. […] M. Jacques Tasset, the son of the famous engraver of medallions, and one of the passionate disciples of M. Léon de Rosny, has just declared himself to be a downright practicing Buddhist. Every evening he will examine his conscience; he will feed only on vegetables, carefully filter his drinking water to avoid swallowing flesh in the form of microbes, etc, etc. […] La Tour d’Auvergne was the first grenadier of France; Mr. Jacques Tasset will be the first monk. It's always like that! (“Un future prêtre bouddhiste,” Le Petit Moniteur Universel, June 16, 1891). In July 1892, Tasset went to the second annual European convention of the Theosophical Society in London as a member of the French delegation (The Theosophist, vol. 13, no. 12, September 1892, p. xciv). He also attended the ninth Congress of Orientalists with Léon de Rosny, held in London in September of that same year (AN, F/17/3008).

It was during this period that he met the Swedish painter Ivan Aguéli (1869-1917), who had come to Paris to study under the direction of Émile Bernard. Bernard and Tasset, who was perhaps at the origin of the painter's pseudonym (Aguéli's real name was Moberg), or his cryptic interpretation (Aguéli for Aulus Gelius), introduced the latter into the Ananta Lodge of the Theosophical Society de Paris (Wessel V., 2021, p. 20, according to memoirs of Tasset delivered orally in 1939 to Axel Gauffin, 1877-1964). One can only imagine the conversations between avant-garde painters in search of new artistic and spiritual forms and the student of Asian studies, who at the same time devoted two articles to Japonisme (Tasset J., 1891a and 1894a). Hailing Samuel Bing (1838-1905), Roger Marx (1859-1913), and the publication of the journal Le Japon Artistique (1881-1891), he praised the allures of the Orient: "the contemporary movement in favour of introducing the fruitful inspirations of oriental genius into Europe is not, as has been lightly put forward, a fashion. It is the continuation of a tradition, whose duration can be numbered in centuries, and which is now beginning to bear fruit. […] To signal the introduction of oriental art in Europe is to announce that the spirit of another race is penetrating our lands. The East invades us; peaceful, it conquers us as much as we conquered it, formidably, with the roar of our cannons. We wanted food, but instead received a soul. […] The masterpieces of Japan and China cannot make us forget those of the Middle Ages and Greece. The introduction of the Buddhist doctrine in Europe will not lead us to misunderstand either the beautiful teachings of the pagan culture, nor all that we owe to Christianity." (Tasset J., 1894a, p. 70)

Tasset published no books, but took on editorial duties as secretary of the Sinico-Japanese Committee. In 1891, he also created the review Le Lotus : recueil pour servir à l’étude de la science des religions comparées, publié sous les auspices de la société d’ethnographie (section des Religions comparées), which was published until his departure for Asia in 1894 and in which he wrote the first article, "Le Christ et le Bouddha" (Tasset J., 1891e). He also published critical reports of lectures and small articles expressing his ideas. In 1890, in the first article bearing his name, he commented on a conference by Philippe-Édouard Foucaux on nirvāna and took note of the change in perception of Buddhism in France: "We regret, for the intelligence of the Buddhist doctrine and for the acquisition of the contingent of ideas which it brings to universal thought, the hopeless interpretation, and it is now permissible to say erroneous, which for a long time remained attached to this sublime conception of Nirvana and which does not yet seem entirely forgotten": he thus condemned the pessimistic and nihilistic conception inherited from Eugène Burnouf (1801-1852) and Jules Barthélemy-Saint-Hilaire (1805-1895) of nirvāna as "nothingness" and affirmed, according to the reading of Foucaux from the Milinda Pañha attributed to Nāgasena: "Nirvana is the cessation of becoming" not "cessation of being". To the question of Foucaux who wonders why there are Buddhists in Paris, Tasset answers, in the line of Rosny, that precisely "this is why the incredulous French accept on this nascent day the new guide which comes to them from the East, the guide they encounter in the study of the radiant doctrine of Çâkya-Mouni" (Tasset J., 1890, p. 28). In 1891, he again underlined how "the law of kindness and appeasement which is the basis of Buddhist doctrine responds justly to the feelings of compassion and pain expressed in many works of our contemporary literature" (Tasset J., 1891d , p. 84).

His contributions sometimes focus on unexpected subjects: he welcomed the law on the abolition of "horse racing and pari-mutuel", arguing that "Ethnography shows that all gain without work is ruinous by the conscience of the people" (Tasset J., 1891c, p. 57). Most of his writings, however, support the thought and projects of Léon de Rosny, of which the "conscientious method" and "eclectic Buddhism" were the most speculative developments: after individualism and the analytical attitude of the 19th century, the next century would be placed under the sign of synthesis, "as infallible as the coming of summer in our climates when the sun goes up to the Tropic of Cancer", because in politics, science, art, "religion and finally in philosophy, the reception given to Buddhism and the predilection of minds for Christianity with pantheistic tendencies [...] allows us to move forward with assurance that the future will prefer a kind of monism more or less pantheistic and a god whose attributes we will not hasten to specify, to the atoms and monads which form the starting point of our materialist and spiritualist schools still in force, as well as to the anthropomorphised god who looks too much like a deification of the individual” (Tasset J., 1891b, p. 86).

At the Theosophical Society, Tasset distinguished himself with his opening speech at the January 1894 session featuring Toki Horyu (1854-1923) (Le Lotus bleu, 1894, p. 324), a Shingon priest passing through France at the end of the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893 and who celebrated a Buddhist ritual at the Musée Guimet in November 1893 (Boussemart A., 2002). Tasset also translated Toki Horyu's speech (Tasset J., 1894c). Another significant meeting took place at Ananta Lodge with Alexandra David, the future Alexandra David-Neel (1868-1969), with whom he maintained an epistolary relationship until at least the start of the First World War (Archives of the MADN). It was certainly Tasset who recommended Alexandra David-Neel to Léon de Rosny and urged her to enrol in courses at the École des langues orientales and the EPHE, and to follow those of Philippe- Édouard Foucaux, whom he frequented on the editorial board of the Sinico-Japanese Society. Finally, it seems that Tasset and David-Neel met Hong Jong-u (1850-1913), the first Korean scholar to come to Paris from December 1890 to July 1893, either at the Musée Guimet, whose library they visited frequently, or at the Theosophical Society (on this meeting and on Hong, see Thévoz S., 2019, pp. 41-42). Hong participated, along with other Asian scholars from India, Indochina, China and Japan, in the program of translations of Asian texts that Émile Guimet (1836-1918) had associated with the life of his museum.

The meeting with Hong was as decisive for David-Neel who planned to join the Korean scholar in his country (Myrial A., 1903), as for Tasset. On June 2, 1893, Tasset sent a request for a mission to the Ministry of Public Instruction to "study Korea from an ethnographic, linguistic point of view and everything related to its civilisation". He justified his request as follows: "An exceptional circumstance now urges me to request this mission to Korea. Bonds of friendship, linked with the only Korean man of letters to come to Europe so far, make me hope to greatly facilitate my introduction into the Korean literary milieu, if I make my departure coincide with the forthcoming return of this Korean to his country. My task, after my introduction among the natives, would be to initiate myself as completely as possible into the language, the ideas, the knowledge, in a word, into the civilised life of the Koreans, into what is most remarkable and most likely to interest the intellectual and learned world of Europe. A stay of three years seems necessary to push this enterprise far enough." (AN, F/17/3008) Émile Guimet added a word of recommendation at the request of Tasset, who left on February 15 from Toulon for Saigon from where he continued to Seoul, then Japan where he stayed in particular in Kobé and Nagasaki, from where he returned via North America (Bernard M.-A., 1927). We also know that Louis-Édouard Bureau (1830-1918), of the Muséum d’histoire naturelle, contacted Tasset about botanical collections, but it seems that Tasset did not contribute to the museum’s collections. He did, however, bring back some grains, especially beans, still grown after him by the family under the name "yache".

On his return, Rosny credited Tasset with having "provided [his] lecture with very valuable assistance in the interpretation of the sacred terms used in the ancient sacred books of China and Japan" (Annuaire de l'École Pratique des Hautes Études, 1896). In 1897, he enrolled again at the EPHE for a year in the course of Léon de Rosny; on his registration form, signed April 18, 1898, Tasset boasts of "a few memoirs in the publications of the Société d’ethnographie" and of a "three-year stay on mission in the Far East" (AN, 20190568214). Tasset evidently continued his research with a view to writing a thesis (Annuaire de l'École Pratique des Hautes Etudes, 1900); little is known, however, of the state of progress of his work, the latter having doubtless been abandoned around 1900.

In 1897, Tasset had addressed, with the support of Rosny, a new request for a mission to the Minister of Public Instruction in order to travel in the spring of that year to the British Museum in London to copy ancient Shinto texts unavailable in France. Rosny mentioned Tasset's plan to make a new trip, at his own expense, "in eastern Asia": if we have no proven trace of this second trip to Asia, it seems possible to affirm that Tasset had by his thesis project sought to contribute to finding "the solution of one of the greatest problems of ethnography in the Asian world", as Rosny put it in his letter of April 22, 1897 (AN, F/17/3008). What was this problem? One might assume that Tasset's lecture to the Société d’ethnographie, upon his return from London, on the Japanese origin of Korean writing and its precedence over the Indo-European systems, followed by a lecture on the same subject in 1904, the last we know of him in the learned circles of Rosny, provide significant clues to the response (Le Libéral, March 16, 1897, L'Ordre de Paris, March 16, 1897). It was a lecture on the Yi king, the result of research undertaken during his mission, in which Tasset argued that the Chinese term yi ("to become") translates the Sanskrit of Buddhist samsāra and corresponds in Greco-Latin culture to the myth of Janus (La Dépêche coloniale, March 9, 1904). Other contributions evoke ancient philosophical doctrines (Tasset J., 1898), esoteric Buddhism in Asia (Tasset J., 1897) or tai-chi (La Souveraineté nationale, April 4, 1897).

Within the framework of the Alliance scientifique universelle, Tasset contributed to a reflection on universal scientific language (Tasset J., 1900). It was during this period that Tasset became active in neo-Latinist circles around Émile Lombard and the review Concordia (Le Rappel, March 21, 1899) and is committed to the conservation of the conservation of languages and patois (Le Rappel, December 26, 1899). This inflection towards "classical" culture, whose importance to Tasset is evident in many of his contributions, regardless of his interest in Asian cultures, seems to have left a lasting mark on the rest of his life’s course; it is the subject of his last known article (Tasset J., 1927). Michel-Ange Bernard, son of Émile Bernard, described his departure from Paris for the Yonne in the portrait dedicated to him in 1927, "Jacques Tasset, théosophe latiniste et provincial":

"He first adhered to theosophy, in which he thought he found the benefits of Eastern wisdom, but soon he turned to Latin, the receptacle of Western traditions, and devoted himself entirely to the study of this overly despised language. Leaving aside the Orient, whose motionless wisdom had seduced him at first, he turned to the Catholic Church, the last incarnation of Mediterranean civilisation. […] Withdrawing to a small town in Burgundy, Jacques Tasset never abandoned the task he had undertaken. Solitude, on the contrary, was a fruitful source of activity. Reading and meditating, being interested in all the movements of his century, he bends his erudition and his mind to the needs of the latter. He currently lives in the small town of Tonnerre where he seems, by his refusal to travel, to have decided to settle down. He does not view things from the perspective of a devotee, but of a philologist and an admirer of the social order. Since then, his activity has taken a definite direction; and, led by the spirit of generalisation, he seeks to gather ideas into synthetic groups in which human aspirations, both present and secular, will be reconciled" (Bernard M.-A., 1927). In regards to him, Élémir Bourges is said to have written to Émile Bernard: "He has a very 16th century spirit, symbolic, bizarre, and subtle, like a Gérôme Cardan or a Calabrian Pythagorean. It is really only in the provinces that we have time to know something." (Bernard M.-A., 1927).

Since 1901, Tasset lived as a "man of letters" in Burgundy, at Molosmes, where on September 24, 1904 he married Aline Fèvre (1858-1924), before the couple moved to Tonnerre (Archives municipales de Tonnerre, Marriage Act; Tasset G., 2021 and Laporte M., 2021, see these references for more details on the end of Tasset's life in Tonnerre). Like many of his contemporaries, attracted by the Orient in the 1890s, he turned away from it at the beginning of the new century. It seems that Tasset did not withdraw entirely into solitude, not only because Émile Bernard visited him often and also settled in Tonnerre, but also because he went with his wife to visit Alexandra David-Neel and her husband in Tunis, probably in 1906 (Le Rappel, March 13, 1906 and MADN archives). On her return from Asia, David-Neel also noted in her diary that she had visited Tonnerre from 11 to 14 May 1927, and again on 4 May 1934. Little is known of his late literary activities.Tasset co-founded the Société artistique et historique de Tonnerre in 1938 after probably published in the local press, as evidenced by a review in 1911 of a book by Alexandra David-Neel (Tasset J., 1911) also published in a French journal in England (Tasset J., 1912). Two letters from Jacques Tasset preserved in the archives of the Maison d’Alexandra David-Neel not only retrospectively document their relationship, 20 years after their meeting at the Theosophical Society, but also give their perception of their respective trajectories. Thus Tasset, in his letter of February 24, 1912 (the other is dated December 22, 1914 and gives his reflections on the war), goes back to his "Buddhist" years and to the Orientalist career which he abandoned and which, for his part, David-Neel continues:

“I cannot share your hatred of Catholicism, to which I owe the same justice as to other religions. I realise that it is very different from the picture of it that was given to me. It is the most tolerant and broadest of doctrines, the most indulgent to human foolishness, the most exacting to the gifted and responsible soul. But Catholicism is very poorly known, priests are often wrong, and must be called to order. As for the profane, they are as ignorant of the doctrine as of Latin. I completely agree with you that practice is necessary. It takes 15 years of school to prepare an attorney, a sixth grade teacher, or a country priest. Do you believe it takes less time to make a Monk or a Brahmin? I renounced Orientalism for this reason. I didn't want to repeat in Japan the eight years of study that I had to do in high school before entering science: elementary. One cannot begin university studies until one has received the mental training of the gymnasium. A true oriental master will ask you, before instructing you, if you possess the Indian culture of his students: what are the çâstras [sic] that you can recite and explain in the original language? The Orientals listen with curiosity to a European. Our students would have some success with a Chinese woman who came to teach them, in Russian, Roman law, or Greek philosophy. Would they be convinced? I do not pretend to know either the Hinayana or the Mahâyâna. I don't prefer either one. I leave them to those who have studied them all their lives: to the Buddhists of Asia. But I fight atheism in its oriental disguise. I defend my fellow citizens against the poison which has already done so much harm to France" (Archives of the MADN).

In some unpublished letters to her husband (Archives de la MADN), David-Neel openly comments on the letters of "the ineffable Tasset", whom Philippe Néel met, recalling their years together in the Theosophical Society (Monastery of Lachen, letter of February 8, 1915) and their discussions on the causes of paranormal phenomena, such as that of the "quick foot" of which she finds an equivalent in Tibet in the form of rlung sgom (or rkang gyogs, Rungpo [Sikkim], letter of February 13, 1914). She paints a deliberately caustic portrait of this "only child of a very well-to-do father" who "kept crying misery" (De-chen Ashram [Sikkim], letter of October 7, 1915) and who speaks Latin. It is again with a halftone evocation that she comments on Tasset's view of the war: "This extraordinary being speaks of the great debacle announced by the Iliad, the Mahabhārata and the Prophets of Israel. He sees it in the current war. His letter is a poem! Although he is one of my very old friends, a companion of youth and university, I cannot help but find him zany to the highest degree" (letter of February 8, 1915).

In chiaroscuro effect, this exchange reveals two trajectories that crossed very closely before diverging, despite the bonds of friendship, in opposite directions. The discretion and singularity of a character like Tasset should not, however, allow us to forget how instructive his career is on the multiple aspects under which France's relations with Asia were considered and reflects its historical shifts.

The Collection

It seems unlikely that a learned and well-to-do traveler like Jacques Tasset brought nothing back from his trip to Asia. In fact, on his return, the press echoed his trip and its material results: "Mr. Tasset […] brought back many original documents on the native religions of China, Korea and Japan" (La Souveraineté nationale, April 4, 1897, p. 1). We can therefore be justified in assuming that the collection consisted essentially of manuscripts and works lacking in French and European collections. In the absence of any Tasset collection, perhaps this bibliophilic assemblage joined the collection of Léon de Rosny. Jacques Tasset does not seem to have left his family an Orientalist library, which nevertheless must have existed and certainly contained works of interest. The inheritance file, found by Gérard Tasset in the archives of the town of Tonnerre, only mentions his assets in real estate, without mentioning a collection of Asian objects or of any art whatsoever (the portrait that offered Émile Bernard was perhaps the only painting in his possession). In the family, interviewed by Martine Laporte, there are only a few Japanese or Chinese vases transformed into lamp bases.

Nevertheless, there is a reference to Japanese objects offered by Jacques Tasset to Alexandra David-Neel in her correspondence with her husband. On 21 December 1928, asking her husband to send her objects left in North Africa to "Samten Dzong", her newly acquired house in Digne-les-Bains, David-Neel mentions "the little Buddha that was once sent to me by Tasset, when he was in Japan". On December 21, 1928, asking her husband to send her objects left in North Africa to "Samten Dzong", her newly acquired house in Digne-les-Bains, David-Neel mentions "the little Buddha who was once sent by Tasset when he was in Japan." This statuette of a standing Amida (MADN, DN-150), visible in numerous photographs showing David-Neel surrounded by Asian objects at different stages of her long trajectory (DN-23 around 1898 in Paris, DN-19 in 1901 in Tunis, DN-204 in the 1960s in Digne), is to this day the only proven vestige of the collection of Asian art gathered by Jacques Tasset during his unique and studious trip to Asia.

Tasset, whose Orientalist heritage has today been greatly erased by time, had certainly hardly foreseen that this gift sent from Japan would link him as closely as possible and well beyond his own disinterest in Asia to the construction of the public image of his "dear and good friend", whom he knew by the changing names and faces of Alexandra David, Mitra, Alexandra Myrial, and Alexandra David-Neel, a figure so close to him by his contradictory aspirations and so distinct by the development of his viatic and literary trajectory.

A final trace of Tasset's collection, still much more tenuous, survives elsewhere in the archives of Alexandra David-Neel: it is likely that before his departure for Asia, Tasset entrusted or offered to Alexandra David some works from his Orientalist library in European languages that would have been useful to her. In any case, this is what is suggested by some of the oldest books on Asia kept in the library of Alexandra David-Neel, which present annotations in sinograms. This hypothesis is supported by a copy of Guillaume Pauthier's work, Chine ou Description historique, geographical et littéraire de ce vast Empire, d'apres des documents chinoises (Paris: Firmin-Didot, 1837): on the title page, Alexandra David-Neel notes that the work was acquired in 1893. A sheet was slipped between two pages of the book on which the calligraphy in ideograms of Tasset's name is written in ink; in the margin in pencil is its transcription in katakana. The characters 達世were obviously chosen by (for?) Jacques Tasset in view of their auspicious character, the first meaning "accomplished, to reach" and the second "world (of existence), life, time..." These traces of his collection testify at once to its virtual existence, the reasons for its disappearance, and possible modes of survival of the objects.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne