VAN GOGH Vincent (EN)

Biographical article

Vincent Willem van Gogh was born on March 30, 1853 in Groot-Zundert, a village in western North Brabant (Netherlands). He was the son of Theodorus van Gogh (1822-1885), pastor of the Reformed Church, and Anna Cornelia Carbentus (1819-1907), daughter of a bookbinder from the court of the Duchy of Brabant. The family had six children (apart from a first child, stillborn, named Vincent Willem I): Vincent Willem —the future painter—, Anna Cornelia (1855-1930), Théodore (Théo) who supported him morally and financially, then Elisabetha Huberta (1859-1936), Willemina Jacoba with whom he corresponded (1862-1941) and Cornelis Vincent (1867-1900). A first child, named Vincent Willem I, was stillborn.

He was torn between the family’s religious tradition with his father and his grandfather Vincent Van Gogh (1789-1874) being Protestant ministers - and the art trade in which his three paternal uncles, including Vincent dit Cent (1820-1888), were active art traders . The latter was associated with the Parisian firm Goupil & Cie, an art and print dealer. Vincent left home at the age of 16 to join the branch in The Hague as a clerk; where he began to collect photographs, photo engravings and prints sold at Goupil.

Between art trade and religious vocation

In May 1873, Vincent was hired to work at Goupil’s London store. He visited the South Kensington Museum where it presented its collection of Japanese objects at the Universal Exhibition of 1862, under the impetus of Rutherford Alcock (1809-1897) one of the first British diplomats in Japan.

Between 1874 and 1875, he was first sent to the Paris headquarters of Goupil & Cie, back again to London and finally returned to Paris. Thanked by Goupil & Cie in April 1876, he returned to London where he became involved in religion as a master and then an auxiliary preacher. Between January and April 1877, he studied theology in Amsterdam staying with his uncle Johannes van Gogh (Jan), a rear admiral of the Dutch navy, who had traveled regularly to Japan in the 1860s.

In 1878, Vincent lived in Brussels and began training as an evangelist. He failed in his studies and traveled the Borinage region as a lay preacher supporting the miners and peasants cause against their living conditions that he captured in his drawings.

A life devoted to art

In August 1880, he decided to devote himself mainly to art, enrolling at the Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels on the advice of the painter Willem Roelofs (1822-1897). When he moved to The Hague - between 1882 and 1883 - he received painting lessons from his cousin by marriage, the painter Anton Mauve (1838-1888) and visited museums.

In the meantime, Théo had found a permanent job at Goupil & Cie in Paris at 19 boulevard Montmartre. In 1881, he was appointed manager of the store and began to provide for the needs of his older brother.

Between December 1881 and September 1883, Van Gogh lived with Sien Hoornik (Clasina Maria Hoornik, 1850-1904) and his child, and practiced various drawing processes including Sorrow chalk, lithographs and oil painting. He collected hundreds of magazine illustrations.

Between September 1883 and October 1885, he stayed in Drenthe (Holland) and then in Nuenen (Netherlands) with his parents where he set up a workshop. He produced a series of some two hundred paintings representing weavers and peasants. The dark palette and expressive brushstrokes revealed his skills as a skilled draftsman and painter.

After the death of his father at the end of 1885, he settled in Antwerp, studied art in churches and museums and enrolled in the local Academy for drawing and painting until February 1886.

From Paris to Arles

In March, he joined Théo in Paris sharing his apartment located at 25 rue Laval in Montmartre. He frequented the studio of Fernand Cormon (1845-1924) and discovered the works of the Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists. In Paris, he met Émile Bernard (1868-1941), Louis Anquetin (1861-1932) ; Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901); Camille Pissarro (1830-1903); Paul Signac (1863-1935) and Paul Gauguin (1848-1903).

His painting changed radically: his palette became clearer and brighter, his repertoire evolved with motifs in cafes, public gardens or places of entertainment. He exchanged his works and acquired Japanese prints.

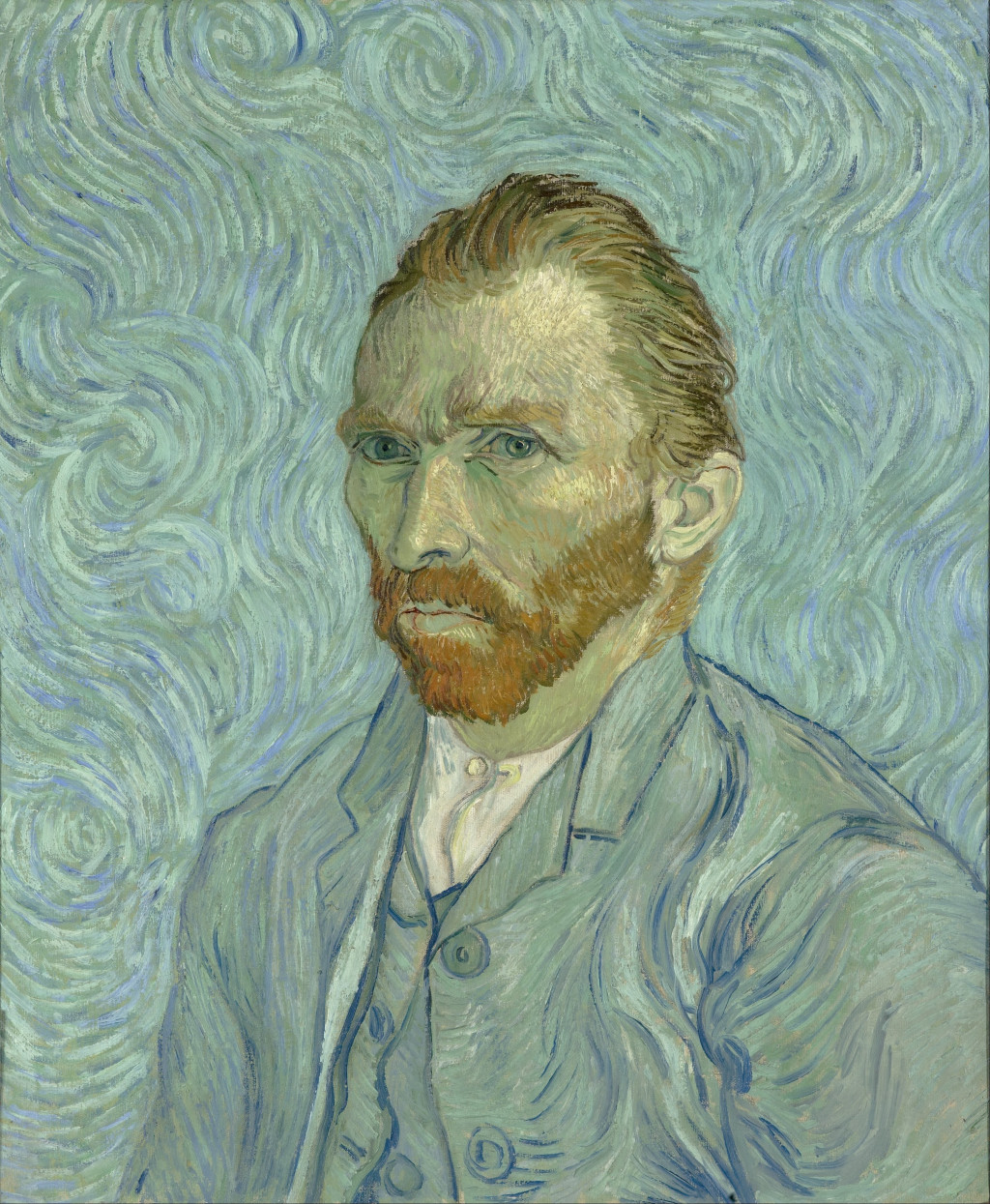

In February 1888, he left for Arles, moved into the Maison Jaune in September and dreamed of making it an "artists' house". Gauguin stayed there between the end of October and December. The episode of the cut ear becomes the subject of his painting a Autoportrait à l’oreille bandée, dit aussi L’Homme à la pipe(private collection) where Vincent represents himself in front of his créponGeishas dans un paysage.

After the 1889 crisis, he decided to be interned and entered the mental asylum of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. In May 1890, after passing through Paris, he went to Auvers-sur-Oise, lived at the Ravoux Inn and was cared for by the doctor-painter, engraver and collector Paul Gachet (1828-1909). He attempted suicide on July 27 and died on July 29, 1890.

A Japanese styled culture

Immerse yourself in Vincent's correspondence written between March 1872 and July 1890 and you will find more than 800 letters, including 658 letters to his brother Theo. These allow you to better understand the complex personality of the man and the artist. His literary writings reveal an ever-awakening curiosity and appreciation of foreign authors. As a young man, he learned English, German and French and read fashionable novels peppered with the Japanese style including Au Bonheur des Dames by Émile Zola ( 1840-1902) in 1884 and Chériby Edmond de Goncourt (1822-1896) in 1885. In Paris in 1886 he discovered (October 10, 1885, letter 534), Bel Ami by Maupassant (August 18, 1886, letter 568) and Madame Chrysanthème by Pierre Loti, whom he mentioned on several occasions (letters 628, 637, 639, 642, 650, 657, 685, 707, 718, 804). He takes Manette Salomon by Edmond and Jules de Goncourt with him to Arles.

As for his (introduction to Japanese art and culture) artistic culture, he first approaches it by reading articles such as in La Nouvelle Revue to which his family subscribes. In 1883, he read a detailed text by Ary Renan (1854-1900) on Japanese art where the author compares Japan "to Holland, Savoy and Provence" (Van Gogh and Japan, 2018, p.167). In his correspondence, he quotes Félix Régamey, whose illustrations he praises as “very strong in Japanese scenes” (letter to Anthon Van Rappard, Monday March 5, 1883, letter 325); and he admired Regamey’s drawings in The Illustrated London News magazine. He also owned several of his woodcuts with Japanese subjects.

He previously had mentioned La Gazette des Beaux-Arts, most prominent in the promotion of Japanese art, and in Arles, isolated from the capital, he read Le Figaro, L'Intransigeant and La revue des Deux-Mondes. Later, he will thank Theo for sending him Le Japon Artistique, and how much he appreciates the quality of the reproductions.

L’estampe as a model

The influence of Japanese prints on Vincent is affirmed by the artist himself: “My work is based on Japanese art” (to Théo, July 15, 1888, letter 640). For many years, art historians have been studying and updating this movement, so it is not useful to mention it unless to provide a summary of conclusions. Van Gogh wanted to be a “modern” painter and recognized as such by his peers. When he arrived in Paris in 1886, his painting changed radically in view of the discussions, exhibitions and contacts with Impressionist and Neo-Impressionist painters. The latter have already done their "revolution" -- clear palette, renewed subjects, original compositions with different points of view, close-up elements, high horizon -- through the "teachings" they collect from Japanese prints. For Van Gogh, this results in (manifests itself in) a nourished and constantly evolving reflection based on his observation of créponsjaponais.

In 1887, he used two prints by Hiroshige from the series of One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, The Sudden Downpour on the Great Bridge near Atake and The Blossoming Plum Grove, to transform them into paintings. To “look more Japanese”, he replaced the white margin of the print with a frame embellished with fanciful ideograms. He did it again with the Courtisane directly inspired by Paris Illustré: Le Japon (no. 45-46, May 1, 1886) whose cover is a reproduction of Keisai Eisen (渓斎英泉, 1790-1848). He let his imagination run wild by adding motifs in the margins taken from four of his prints kept at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. These include bamboos from Hundred Views of Fuji by Hokusai from an illustration of cranes appearing in the plate of Geishas dans un paysage by an anonymous artist, and finally a feuille by Utagawa Yoshimaru (1844-1907) devoted to “Insects and small creatures” including a voluminous frog sitting on a lotus leaf.

Unlike the Impressionists, lovers of 18th century ukiyo-e with soft colors, Vincent admired the garishly colored crépons which have a dazzling effect on the eyes, such as the painting Bateaux de pêche sur la plage aux Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer (Saint-Petersburg, Hermitage Museum). He now uses the pure colors of red, yellow, blue, and complementary ones, creating various trends of the beginning of the 19th century.

His study of Japanese prints encompasses graphic art and, like Hokusai, he draws with dots, small strokes and hatchings of which the expression "shorthand drawing" sums up his technique (Van Tilborgh L., 2018, p. 65) . He even employs an aniline ink of a vivid mauve, now faded, reminiscent of the synthetic-based purple of late prints.

The collection

When, Vincent Van Gogh moved to Antwerp in November 1885, he was already familiar with Japanese art, comparing the docks of Antwerp to a “famous Japanese culture, capricious, characteristic, unheard of – at least we can see them that way.” He reported to his brother, “My studio is quite bearable, especially since I have pinned to the walls a collection of Japanese engravings which amuse me a great deal. You know those little figures of women in the gardens or on the beach, horsemen, flowers, gnarled hawthorn branches” specifying the “black & white” effect of these reproductions in black, gray and white. And to endorse Edmond de Goncourt's expression " japonaiserie for ever " (letter to Théo, November 28, 1888, letter 545).

Acquisition and daily environment

When did Vincent and his brother Theo start buying Japanese woodcuts in quantity? No doubt when Vincent arrived in Paris in February 1886 and lived with his brother at 25 rue Laval (currently rue Victor Massé). Two years later, he announced to his sister Willemien “Theo and I have hundreds of these Japanese prints” (March 30, 1888, letter 590).

From Antwerp to Auvers-sur-Oise, Vincent decorated the walls of his studios. In Paris at 54 rue Lepic, he hung prints, as a souvenir of his brother before leaving for leaving for Arles.

In the Maison Jaune, which was first considered workshop, he thought of "putting ukiyo-e on the wall" (May 1, 1888, letter 602). He installed "all the Japanese items" sent in "packages" by Théo (23 or September 24, 1888, letter 686), and at the beginning of May 1889, he described the works hanging on the walls of his room, in particular the illustrations taken from Japon artistique: " une mandarine de Monorou” [sic] and “ le brin d’herbe” (May 3, 1889, letter 768).

Finally, in Auvers-sur-Oise, at Doctor Gachet's, the painting Marguerite Gachet au piano (Basel, Kunstmuseum, inv. 1635), hung in the young woman's bedroom. It is surrounded by the Courtisane after Eisen and a CourtisaneParadant by Katsukawa Shunsen; these three works in a kakemono type format.

This lot from the estate of the Van Gogh brothers (Théo died in 1891) has been kept since 1973 at the Van Gogh Museum Foundation in Amsterdam. The catalog of the Van Gogh Museum's Collection of Japanese prints lists 482 pieces or 549 sheets (depending on the different counting method for the diptychs and triptychs) including three sets of illustrated books and two small albums of flowers and birds. Additional sheets were added later by donation or acquisition following the offering of 44 prints by the Tokyo Shimbun in 1986 to complete the series of the 53 Tokaido stations (above).

Analysis

If, for reasons of proximity of dates, the chronological breakdown established by S. Bing for the catalog of the exhibition of Japanese Engraving at the School of Fine Arts in 1890 is applied, Van Gogh's collection can be classified as follows:

For the period 1765 to 1806, the date of the death of Kitagawa Utamaro (喜多川歌麿, c. 1753-1806) representing the golden age of polychromy, Van Gogh has only two prints; one by Toyokuni and the second by Eizan . Eighteenth-century prints, in particular by Utamaro, were becoming scarce on the market and therefore not very accessible for modest budgets.

The second period, from 1806 to 1865, marked by the death of Utagawa Kunisada (歌川国貞 1786-1865), 300 sheets are including 2/3 of the collection being 48 prints by Utagawa Hiroshige (歌川広重, 1797-1858 ); 204 Kunisada; 49 Kuniyoshi (歌川国芳, 1797-1861); and 26 Kunisada II (歌川, 1823-1880). No original print is signed by Hokusai despite Vincent's wish to obtain the "300 views of the holy mountain [...]" (to Théo, July 15, 1888, letter 640) i.e. the three black and white volumes of the Hundred Views from Fuji, Fugaku hyakkei by Hokusai; he did have the second volume that was reprinted in 1860.

Finally, the last period, 1865-1905, brings together around 50 plates. They are recognizable by the use of modern inks, aniline and ecoline, producing a colorful and shimmering appearance, much appreciated by Van Gogh. "But whatever people say, the more vulgar crépons colored with flat tones are admirable for me […] I can't help but find these 5 cent crépons admirable – It is more than likely that the other [a SERIOUS amateur] would be a little shocked and would have pity on my ignorance and my bad taste (September 23-24, 1888, letter 686). The main designers are Toyohara Kunichika (豊原国周, 1835-1900) and Utagawa Yoshitora (active around 1836-1907), to which are added Yoshikazu (安彦良和 and Utagawa Toyokuni (1769-1825). These designers "accompanied" Vincent with their "free sheets" on his last trip to Auvers-sur-Oise.

The majority of the prints representing 40 percent of the collection and dating from 1806 -1865, 40 percent of the collection, is devoted to female beauty, sometimes together in triptychs, and to actors in their roles; the publishers thus responding to the wishes of the their customers; these representations belong to the period 1806-1865. Then the landscapes appear with Hiroshige who popularized this theme around 1830. Vincent, sensitive to Japanese nature, favors irises, sakura cherry blossoms and trees either isolated trunks or trees in alignment that structured his compositions.

Between a stock of merchandise and personal collection

The term "collection" henceforth attached to this grouping, belongs neither to the vocabulary nor to the mentality of Vincent who uses, most frequently, "depot" [sic] sometimes that of "heap" or "packages of prints”. Émile Bernard evokes the “crepon bundle” (Bernard E., 1994, p. 313) as does Goncourt the “image bundle” taken from Bing (Goncourt de E. et J., April 4, 1891, t. III, p. 569).

Between "together" and "collection" the ambiguity stems from the fact that Van Gogh himself pursued several goals, oscillating between building a "dealer's stock and [an] artist's collection" (Uhlenbeck C., 2018 , p. 147) and the desire to keep some remarkable pieces, as evidenced by his correspondence with Théo during his stay in Arles between February 1888 and May 1890. He invites him to choose from among the most beautiful sheets "what we like best in the heap remains with us” (July 15, 1888, letter 642), being the foundation of the current collection.

In Paris in 1886, the Van Goghs lived in the district of artists and galleries. On the ground floor of 54 rue Lepic, Alphonse Portier traded in modern paintings, dealing with the Impressionists and collectiing Japanese prints. The galleries of Siegfried Bing (1838-1905), collector, publisher of the magazine Le Japon Artistique, main supplier – with Tadamasa Hayashi (1853-1905) – of Japanese prints and objects, were not far from the home of the Van Gogh brothers, at the corner of 22 rue de Provence and 19 rue Chauchat. Vincent frequents his home at 9 rue Vézelay and more assiduously his "attic" where he stores large batches of second-rate prints. Bing has a reputation for leaving artists for hours to leaf through, study, compare, acquire - or not - Japanese sheets, a way for him to penetrate the circle of artists. "There is a pile of 10,000 crépons [sic ], landscapes, figures, old crépons” confides Vincent to Théo on July 15, 1888 (letter 640). Van Gogh does not use the term print or xylography but only that of "crépon", i.e. a type of woodcut printed on mechanically pleated paper and sold cheaply in Parisian department stores. This term will be taken up by the Nabis such as Vuillard and Bonnard. Strictly speaking, Van Gogh has around ten “real” crépons.

Vincent (first in line) massively acquired Japanese prints to benefit his friends, the artists of the "petit boulevard" including Louis Anquetin (1861-1932), Émile Bernard (1868-1941) and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864 -1901). He declared to his brother "I myself learned a lot there and I made Anquetin and Bernard learn with me" (to Théo, July 15, 1888, letter 642). He considered Japanese prints as a source of regeneration for the world of art of in the second half of the 19th century.

Building up a stock of merchandise to distribute it is not devoid of the need of certain sense of business , especially since Vincent is, through his uncles, involved in the art trade and also having worked at Goupil & Cie in The Hague and Paris. This despite the "disaster" of the exhibition and sale of Japanese prints organized at the Café du Tambourin in February-March 1887, a Montmartre restaurant-cabaret run by his partner Agostina Segatori (1841-1910) and frequented by artists (July 15 1888, letter 640).

This approach is not out of the picture to serve as currency because Théo is manager of the gallery Boussod, Valadon & Cie, successor of Goupil & Cie since 1884. As an elder brother, he advises Théo: “ that will get you a Claude Monet and other paintings because if you take the trouble to unearth crépons, you have the right to trade with painters for paintings” (July 15, 1888, letter 642). And to value their efforts in this way, "Make him [Bing] point out, however, that we gain nothing from it, that we go to great lengths for the business, that finally we are sometimes the cause of sending people to him" (July 15 1888, letter 640).

Several letters addressed to Théo deal with the negotiations envisaged by Vincent and the profits to be made “how I would like to sell all that heap. There's not much to be gained from it, that's why no one cares. Nevertheless, after a few years all this will become very rare, will sell for more. That is why we must not despise [sic] the small advantage that we currently have of rummaging through thousands to make our choice”. He also mentions “a new stock of 660 crépons” (July 15, 1888, letter 642).

Decryption: Portrait du Père Tanguy

A double decryption is necessary on reading some paintings such as the Portrait du Père Tanguy (1825-1894) from 1887 painted in two copies, one acquired by Rodin and kept in the eponymous museum (inv. P.07302); the second in the Niarchos collection. The two have some differences in the background decor. In the first painting, Hiroshige appears with three landscape prints including a view of Fuji in the upper band, the courtesan of Kunisada and to the right of the character, a counterpart to the courtesan of Eisen interpreted by Van Gogh; and then below figures a bouquet of flowers.

The second painting and sketched more summarily is the Portrait du Père Tanguy, that shows a courtesan by Yoshitora (top right) and the two Kunisada with the portrait of an actor and again the Courtesan of Eisen. The bouquet of flowers still appears, and all the prints belonged to Van Gogh with the exception of the ipomées which have not been found. But, as with Eisen's Courtesan, Van Gogh contrives to cover his tracks by inserting in his paintings quinces, lemons, pears and grapes in place of Hiroshige's print. These "wallpapers" work like a kaleidoscope.

Conclusion

This East/West crossing, this mixing of prints and oil paintings are an admission of association and the recognition of Japanese art by Van Gogh which inspires him, nourishes him, and strengthens him. It is not surprising that the Midi, metamorphized into a fantasized Japan, that it was there that he evolved towards a cultural primitivism where he portrays himself as a “monk, simple worshiper of the eternal Buddha” (October 4 or 5, 1888, letter 697).

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne