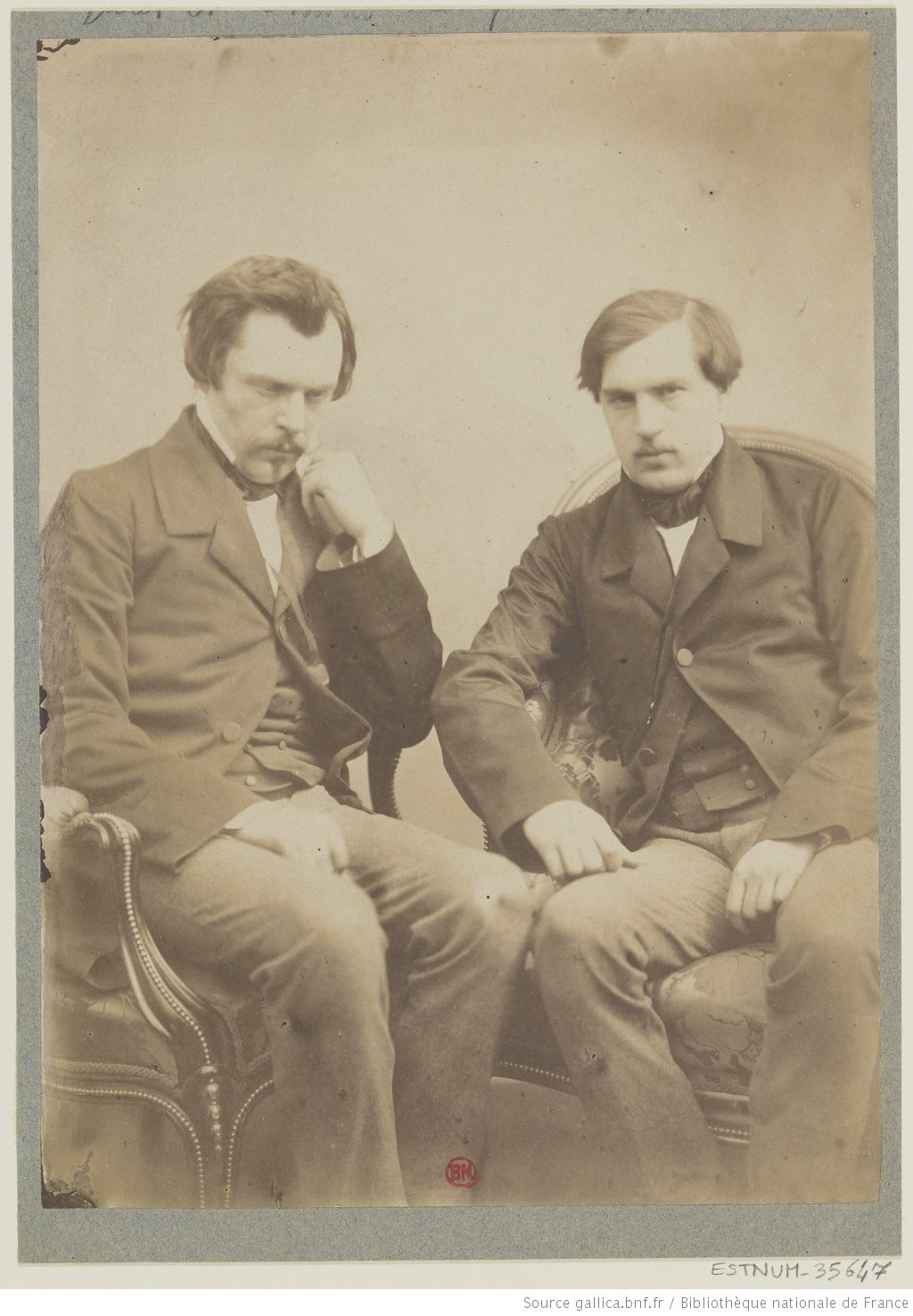

GONCOURT Edmond and Jules (EN)

Biographical Article

For a detailed biography of the two brothers, please refer to the study by Dominique Pety on Dictionnaire critique des historiens de l’art, published by the Institut national d'histoire de l'art. They were naturalist novelists, historians of the art of the 18th century, of which they were great aficionados, and were also interested in the arts of China and Japan, which was gradually accessible in Paris starting in the Second Empire. It is this second aspect that will be examined here.

They staked themselves out as pioneers in this field, at a time when Chinese objects began appearing in large numbers on the Parisian market, especially after the sack of the Summer Palace in October 1860, and the opening of trade with Japan through the treaty signed in Edo in October 1858 led to the presence from 1862 of Japanese books, prints, and objects among merchants who until then had specialised in chinoiseries.

Thus in 1884, in the preface to Chérie, Edmond de Goncourt reported his brother's remarks about their first novel En 18..., in which two Oriental bronzes are described on a fireplace, actually associated with a Tonkinese name. He also claims to have acquired an album of Kunisada and Hiroshige II (whose names he did not know) in 1852 that illustrated the miracles of the goddess Kannon, described at length in 1881 in La Maison d'un artiste, but dating from 1859 (édition Lacambre, 2018, Figs. 27 to 34).

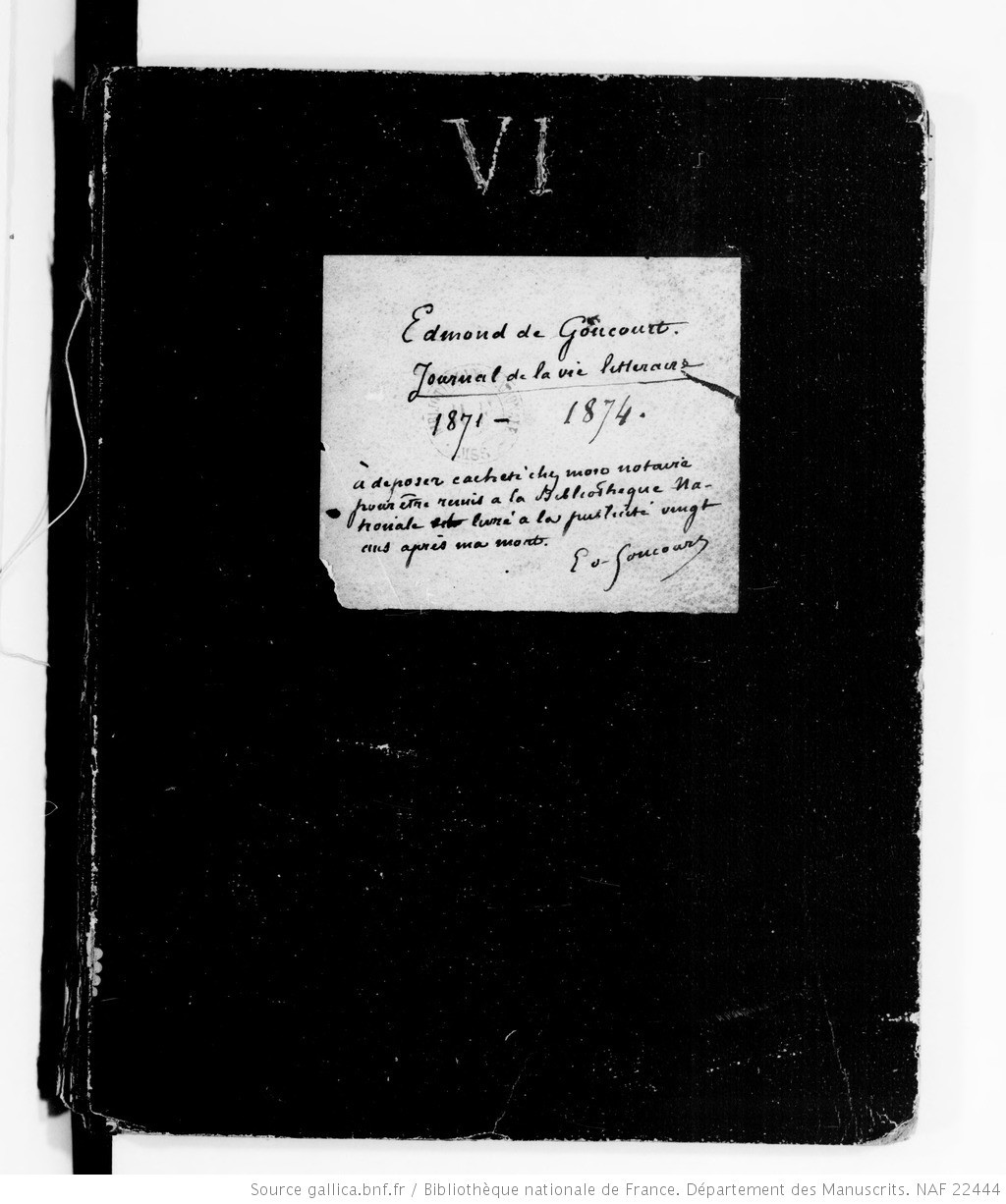

The Journal provides some information on the origins of the brothers’ collection. The entry of June 8, 1861, reports the acquisition at La Porte chinoise, a tea shop established since the Restoration at 36 rue Vivienne, of “drawings by the Japanese", whose "prodigious art" was praised. A few months later, they went to Leiden, whose museum had many souvenirs from Japan, brought back by travellers to Deshima in the port of Nagasaki.

Their acquisition of Japanese erotic prints in October 1863 tells us about the rapid development of imports, including these pieces which at the time were censored in France. These were preferred to the academicism of Greek art, a judgment shared by their friend Princess Mathilde.

Purchases of illustrated albums increased, well before the Exposition universelle of 1867 with its large Japanese section. Take for example the scene in Manette Salomon, in which the novel’s hero, Coriolis, leafs through them, as did the Goncourt brothers.

When they moved into their new home on Boulevard de Montmorency in 1868, they acquired a large Japanese bronze for 2,000 francs that was more than a meter high and adorned their living room. The bronze was probably imported during the Exposition universelle. This appears in the portrait of Edmond de Goncourt, painted in 1888 by Jean-François Raffaëlli, now in the Musée des beaux-arts de Nancy.

They were already familiar with Philippe Burty (1830-1890), a great lover of Japanese art. After the death of Jules in 1870, Edmond took refuge with Burty in the centre of Paris for a few months in 1871 since the district of Auteuil was threatened by bombing.

It was often with Burty that, in the following years, he visited the Parisian shops, both that of Mme Desoye at 220 rue de Rivoli, which specialised in objects from Japan, and those of Bing, or the Sichels, after the return of Philippe Sichel of Japan in 1874 with 450 boxes of various curiosities. In 1879, he also visited the newly opened shop of Antoine de La Narde.

The Collection

The collection described in minute detail by Edmond de Goncourt in La Maison d'un artiste, a work in two volumes, dated June 26, 1880 and published in 1881, includes many Chinese objects. He was a client of Malinet, on Quai Voltaire, where he even found some porcelain from Auguste le Fort (Frédéric-Auguste I of Saxony (1670-1697)), whose duplicates were then being sold by the museum of Dresden.

The Chinese and Japanese objects that he accumulated in his house in Auteuil occupied not only the cabinet of the Far East on the first floor, including its walls and its windows, but also the entrance and staircase, which featured some kakemonos hanging on the walls as well as some vases. The washroom walls were decorated with plates, including Chinese porcelain. In the rooms devoted to the French 18th century, the firewalls in front of the fireplaces were made of framed fukusa, embroidered or printed squares particularly from Kyoto, and were reported by Philippe Sichel to have been numerous.

During the Exposition universelle of 1878, Goncourt met several Japanese individuals who helped him decipher the signatures on his works of art, netsuke, or sabre hilts. This help allowed him to demonstrate a rare erudition praised by his contemporaries, even if he knew nothing of the artists' biographies. He did not inquire about the identities of the authors of the books, albums, and prints that he owned.

Only the name of Hokusai was known to him, and this he associated with the volumes of the Manga and the three volumes of One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji. He believed his date of death to have been much earlier than it actually was. The writer’s precise style makes it possible to attribute other works to Hokusai or to recognise pages by Hiroshige, Kuniyoshi, or Kunisada.

The description of 1880 shows that the items available in France at the time were of recent productions, at most from the foregoing 50 years.

Philippe Sichel observed in 1874, as noted in Notes d’un bibeloteur au Japon prefaced by Goncourt in 1883, that the Meiji era, upsetting the social and religious organisation of the country, introduced objects to the market that had become useless.

The Exposition universelle of 1878 made it possible to discover the most recent Japanese production. There Goncourt bought a luxurious Chinese jade vase, which he placed in the centre of the fireplace of his cabinet in the Far East. It can be seen in one of Lochard's photographs, taken a few years later possibly in view of an illustrated edition of La maison d’un artiste, which never came to be.

It was the trip to Japan in 1880-1881 of the Parisian art dealer Siegfried Bing that facilitated the arrival in France of prints from the 17th and 18th centuries, notably by Kyonaga and Utamaro, as well as the reissue of the Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji by Hokusai (without the censorship stamp, recently eliminated), a series now famous but then completely unknown in Paris.

In October 1888, Goncourt published an article in issue no. 6 of the journal Le japon artistique, founded by Bing in May 1888, in which he described and reproduced an object from his collection: "A pocket writing case made by one of the 47 ronin"; the cover is illustrated with the ronin Otsuka after Kuniyoshi (Lacambre G., 2018, p. 30-31, fig. 4 and fig. 5, and p. 126, fig. 35).

During the exhibition of Japanese engraving (or Japanese masters, as described in the two posters by Chéret) at the école des Beaux-Arts, quai Malaquais, organised by Bing from April 25 to May 22, 1890, Goncourt, who was part of the committee, does not appear as a lender in the catalogue of engravings, but only in a second volume devoted to books and collections: he is listed as the lender of no. 17 by Kitao Masanobu, nos. 133, 134, 135 by Kitakawa Utamaro, nos. 251, 252, 253 by Hokusai, no. 303 by Hokkei, and nos. 396, 397, 398, corresponding to collections by various authors.

Goncourt continued to build his collection, both at Bing, La Narde, and Hayashi. The latter, who came in 1878, was first cited in the Journal in 1883 and soon set up shop as a merchant on rue de la Victoire. In him, Goncourt found not only a supplier of prints, often old, but also a translator and an informant of the first degree. Indeed, thanks to his collaboration, he published monographs on Outamaro (1891) and Hokousaï (1896), and made plans to write many more. In the preface to Outamaro (1891), he defined his project of study, under the aegis of his beloved 18th century, of "five painters [Outamaro, Hokusai, Harunobu, Gakutei, and Hiroshige], two lacquer artists, an iron worker, a woodcarver, an ivory carver, a bronzer, an embroiderer, and a potter".

In 1896, he published, in the Gazette des beaux-arts of February and March, a kind of supplement to La maison d'un artiste, describing the two attic rooms installed in 1884 on the second floor of his house for Sunday receptions of his friends from the world of letters and the arts. Various Chinese and Japanese works of art were displayed on shelves, while on the walls or ceiling hung kakemono and fukusa; a Chinese woman's dress covered the divan and, in the recess of an attic window, were prints by Utamaro (Lacambre G., 2018, figs. 10, 11), Harunobu (fig. 12) and Hokusai.

The Far Eastern Art Sale of March 1897

Having no direct heirs, Edmond de Goncourt provided in his will for the dispersal of his collections: "My wish is that my drawings, my prints, my trinkets, my books, in short, the things of art which have been the joy of my life, do not find the cold tomb of a museum and the dumb looks of indifferent passers-by; I ask that they all be scattered under the hammer blows of the auctioneer, so that the pleasure that the acquisition of each one has given to me may be given again to an heir to my tastes".

So are the writer’s desires recalled at the beginning of the catalogue for the sale Collection des Goncourt. Arts de l’Extrême-Orient which took place at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris, from March 8 to 13, 1897. The auctioneer was M. G. Duchesne, the expert S. Bing (namely the dealer Siegfried Bing, of whom Edmond de Goncourt was a loyal customer, although a controversy about Hokusai broke out between them after 1890; Bing also wanted to write the Japanese printmaker’s biography).

The total number of lots was 1,637, of which 1,575 were European books on the Far East, leaving some 1,574 lots of works of art, books, and prints from China and Japan.

While quotes from La Maison d'un artiste published in this catalogue establish that certain objects were present at the Goncourts’ home in 1880, there is practically no mention of the pieces’ origin. For no. 258 (square cake box in Kyoto pottery, 0.79 m) and no. 690 (a bronze representing a small rooster with a long tail), the collection of Philippe Burty is referenced. But two objects that gave rise to etchings by Félix Buhot, published in the anthology Japonisme in 1883, do not bear this same indication of provenance (Burty). Among the porcelains from China (Youn Tching period [1723 to 1736]) are no. 63, "Large square-shaped tea flask", now at the Musée des Arts asiatiques-Guimet in the Grandidier collection [inv. G4257], for which a proof bears Burty's name, finally suppressed in 1883, and no. 678, a small Japanese bronze: "Bronze incense burner representing a young lord riding a caparisoned mule", without mention of owner.

For no. 686, a Japanese bronze incense burner, the collection of the Duc de Morny is cited. This burner was sold in Paris, after his death, in May 1865: the name of the Goncourts is not found among the buyers, but the merchant Malinet, of whom the Goncourts were customers, bought many lots.

Buyers from all over Europe were present at the sale of the arts of the Far East in 1897.

The main buyer, Bing, obtained 203 lots, some of which were immediately bought (no. 291, no. 424, no. 852) by Justus Brinckmann (1843-1915), who also acquired 48 lots directly. Brinckmann supervised the German version of the journal Le Japon artistique, which waspublished by Bing between May 1888 and April 1891. Moreover, he was the director of the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg, which still conserves its many acquisitions from the Goncourt collection, works of art especially, but also some prints. He also acquired various books on Japan, both that of Father Charlevoix from 1736 (no. 1597) and those of Émile Guimet (no. 1632).

Georges Hugo, painter and grandson of the poet, bought 167 lots, but his collection was dispersed before his death in 1925. A few pieces were found soon thereafter in the Raymond Huet sale of May 14-16, 1928.

The English dealer Arthur Lasenby Liberty (1843-1917) came in next, with 77 lots, and the Parisian jeweller and fanatical collector Henri Vever (1854-1942), with 71 lots.

Raoul Duseigneur (1845-1916), a collector who made donations to the musée des Arts décoratifs, obtained more than 50 lots.

Among the merchants who acquired some lots were, in addition to Bing, Hayashi Tadamasa, Mrs. Florine Langweil, and Laurent Héliot, 62 rue de Clichy, who bought 26 lots for Grandidier, donor of the collection of Chinese ceramics of the Louvre (now at the Musée des arts asiatiques-Guimet). Thus, among the thirteen Chinese porcelains from the Goncourt sale that were donated immediately by Ernest Grandidier (1833-1912), at least one dish with a chickadee and a square Chinese tea flask was mentioned in La Maison d'un artiste in 1880. These were decorated with birds on branches (inv. G 4357) and were reproduced in the sales catalogue (the only one described in La maison d'un artiste). This flask (no. 63, acquired for 700 francs by Heliot), which was the subject of an etching by Félix Buhot, came from Philippe Burty. The album of ten etchings, Japonisme, is present under the number 1586 of the Goncourt sale, with this valuable comment: "Reproduction of objects having belonged for the most part to the collections of Ph. Burty and Edmond de Goncourt".

The landscape painter Georg Oeder (1846-1931), a great collector from Düsseldorf (Delank, 1996, p. 79-92), also bought several Japanese ceramics at the Goncourt sale, and Larkin, from London, obtained 34 lots.

Woldemar von Seidlitz (1850-1922), who was familiar with Goncourt's publications and the French collections of Japanese prints, as evidenced by the illustrations in a book published in 1897, worked at the Dresden Museum between 1885 and 1916, for which he bought five lots of old Japanese prints and three Chinese porcelains at the Goncourt sale.

The Lorraine industrialist Charles Cartier Bresson acquired 31 lots. Part of his collection is in the Musée des beaux-arts de Nancy, which was bequeathed by his widow in 1936. Thus, from the sale no. 605, this museum now holds a leather smoking kit (Un goût d’Extrême-Orient, no. 60, repr.), no. 630, a portable copper writing desk (Un goût d’Extrême-Orient, 2011, no. 58, repr.), andno. 845, a sabre hilt signed by Kawaji Tomotomi (1692-1754) (Un goût d’Extrême-Orient, 2011, no 40, repr). No. 488, a lacquer box with five lobes (L'Or du Japon, 2010, no. 166, repr.: Un goût d’Extrême-Orient, 2011, p. 27, fig. 13-14), was acquired for 200 francs on December 12, 1899 by Cartier-Bresson at Fèvre et Deschamps, who must have obtained it from Mrs. Langweil, whose name is listed for this object in the minutes of the sale.

In Raymond Koechlin's bequest, in 1931, the Bibliothèque nationale notably received the Livre de dessins pour artisans. Nouveaux modèles from 1836, by Hokusai (Marquet, 2014, p. 24-25, with integral reproduction), which had been acquired at the Goncourt sale (no. 1525) by Henri Vever.

Purchases by other connoisseurs are sometimes found in subsequent public sales. According to Jude Talbot, a kosuka (sword accessory) from Goncourt was acquired by Georges Marteau at the Garié sale of March 5-10, 1906 (no. 1579). Bing bought it at the Goncourt sale (no. 882). This small object was part of his bequest in 1916 to the Louvre and was then transferred to the Musée des arts asiatiques-Guimet (inventory EO2339, currently not located). Georges Marteau had also offered to bequeath a rich little cabinet in Japanese lacquer, which he had acquired under no. 206 of Paul Brenot's posthumous sale of June 5-10, 1903 (Talbot, 2019, p. 19). The name of Brenot is well noted in the minutes of the Goncourt sale for this object, described at length at no. 439, but it was not among the pieces selected in 1916 by the Louvre. Its trace was lost after its appearance under no. 60 of the sale, on February 25-27, 1924, of the remainder of the Japanese collection of Georges Marteau by Ferdinand Seiler, his universal legatee.

The Pincé museum in Angers has a sake cup (no. 503), decorated with cranes and bamboo on a golden background that was acquired much later, in 1948 (L’Or du Japon, 2010, no. 165, repr.).

Despite the prestige of this 1897 sale, mention of which is sometimes still found on a miraculously preserved label, many objects remain to be located. These would allow us to truly assess the taste of the Goncourts, these key witnesses to the evolution of the Parisian market for Chinese and Japanese art at the end of the 19th century.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une famille

Personne / personne

Personne / personne