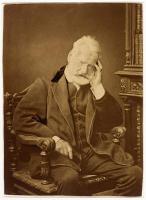

HUGO Victor (EN)

Biographical article

Born in Besançon, France, in 1802, Hugo spent most of his youth in Paris, where he published his first poems, Odes et ballades and his first novel, Han d’Islande, in his early twenties. The two publications initiated a meteoric literary career that quickly propelled Hugo to international fame. They were also the beginning of a prodigious literary output, including poetry, novels, and plays, many of which, likeLes Misérables and Notre Dame de Paris, are popular to this day. A royalist by upbringing, Hugo subsequently turned republican. He played an active political role during the Revolution of 1848 and the Second Republic. But when the president of the republic, Louis Napoléon, seized power in 1851 to create the Second Empire a few months later, Hugo left France in protest. He traveled to Brussels and Jersey before settling in Guernsey, where he would live in self-imposed exile from 1854 to the end of the Empire in 1870. By the time he returned to France, Hugo had become a national hero. He was elected to the Senate in 1876 and his eightieth birthday in 1882 was a national celebration. He died three years later, in 1885, and was interred in the Pantheon. Hugo was not only a writer but also an artist, well-known for his thousands of ink drawings as well as for the unique interiors he designed, especially in his family home in Guernsey, Hauteville House, and in the nearby cottage of his mistress Juliette Drouet (1806-1883), Hauteville Fairy (Decaux A., 2000).

CC0

Hugo as collector

Hugo’s collecting practice was intimately related to his activities as interior decorator, which may have begun in 1832 when, together with his wife Adèle Fouchon and their four children aged 2 to 8, he moved to a large apartment at 6 Place Royale (now the Maison de Victor Hugo on the Place des Vosges). Unusually for that time, Hugo furnished the entire apartment with antique furniture and objets d’art (Eudel P., n.d., p. 296). Upon a visit in 1847, Charles Dickens described it as a place filled with “old armour, and old tapestry, and old coffers, and grim old chairs and tables, and old Canopies of state from old palaces and old golden lions going to play at skittles with ponderous old golden balls” (https://libwww.freelibrary.org/digital/item/32286). The theatrical character of the interior was confirmed by Eugène de Mirecourt (de Mirecourt E., 1854, pp. 24-27), who drew special attention to the “marvelous museum” in Hugo’s cabinet de travail, which was filled with Renaissance furniture and tapestries, medieval manuscripts, and Far-Eastern ceramics, lacquerware, and figurines. Hugo’s poem “A des oiseaux envolés” (22 April 1837), likewise evokes this cabinet with its “Chinois ventrus, faits comme des concombres,” a reference, no doubt,to the kind of Chinese export porcelain figurines that were popular in the nineteenth century. After the 1848 Revolution, Hugo moved to the rue de la Tour d’Auvergne, where he would remain until his departure from France in 1851. Théophile Gautier (1874, passim) would later give a description of this apartment, his memory triggered by the chance discovery of the catalogue (not extant today) of the auction of the contents of Hugo’s apartment. According to Gautier, it was filled with antiques and furniture of all periods and geographic areas, including Chinese water dispensers, tapestries, and bamboo chairs, as well as Japanese lacquer cabinets and porcelains.

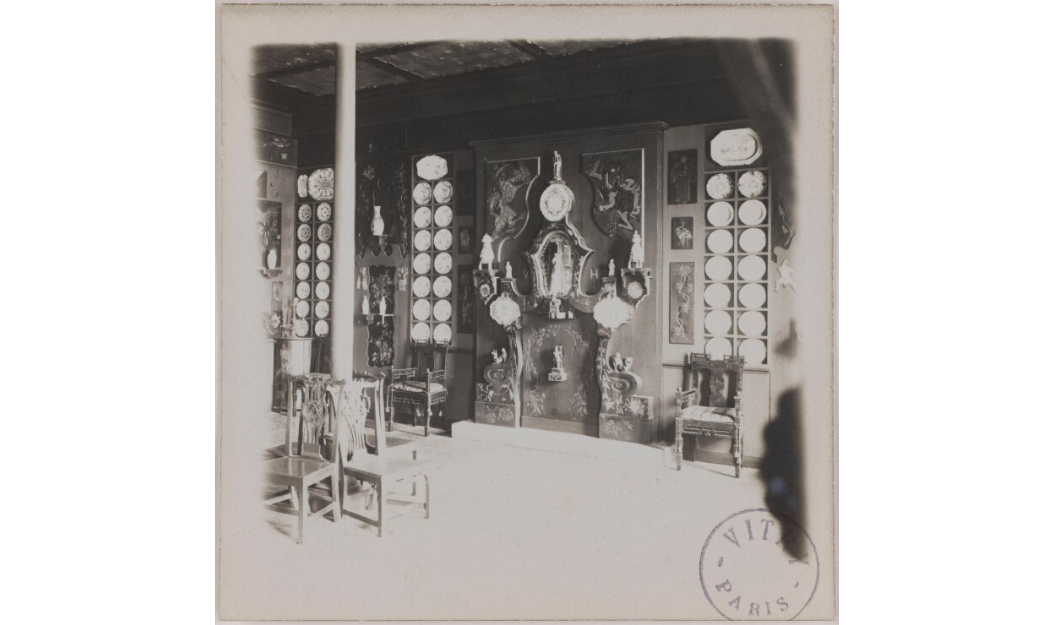

AfterHugo moved to Guernsey, he bought a family home in spring 1856, which he called Hauteville House, after the street on which it was located. He decorated the home in two phases, 1856-59 and 1861-62, furnishing it with antiques of all periods, as he had done before. But while in the apartments in Paris, antiques were freely mixed up, in Guernsey Hugo came to prefer greater (though never complete) stylistic unity, creating some rooms that had a medieval or Renaissance character, others that looked more baroque, and others again that had a Far-Eastern flavor. The latter was especially outspoken in the Blue and Red Salons on the first floor, named after the coloration of their silk wall coverings soie (Hauteville House Guide 2010 et 2019).

Provenance

Where did Hugo obtain the countless antiques used to decorate Hauteville House—either whole or taken apart and often given new purposes (Chu P., 2020)? His agendas from Guernsey (Hugo V., 1969, 1327-1492), in which he noted events of the day as well purchases and expenses, give us some information as to where, when, from whom, and for how much he bought certain items, though it is generally difficult to match his cursory descriptions with the actual objects in the house. It appears that Hugo was an opportunistic collector, who bought when and where he could. A few objects were brought over from France; others were purchased from, or exchanged with, other French exiles living in Guernsey or Jersey. Others, again, were acquired in London or on the European continent, either by Hugo himself during short trips, or by friends and relatives on his behalf. It is possible that some objects were gifts. Hugo also appears to have scoured the local brocanteries in Guernsey, often together with his mistress Juliette Drouet for whose nearby house he designed and helped furnish two rooms in Chinese style. Unlike Hauteville House, which has remained intact, Drouet’s Hauteville Fairy was gutted but the Chinese drawing room, designed by Hugo, was preserved and transferred to the Maison de Victor Hugo in Paris (Chu P., 2019). Among the Far-Eastern objects in Hauteville House whose provenance are known is the bronze peach-shaped incense burner in the Blue Room, which once belonged to Alexandre Dumas. The writer gave it to Hugo’s wife Adèle to be sold in a charity bazar benefiting indigent Guernsey children ((Hauteville House Guide, 2019, p. 34). According to his agendas, Hugo bought the object at the bazar on June 25 for 100 francs Hugo V., 1969, p. 1334). The agendas also tell us that he bought the small statuette of a, “idole chinoise sur son throne” in Guernesey for “32 sch.” but the seller is not known (Hugo V., 1969, p.1340).

Far-eastern collection in Hauteville House

Before discussing Hugo’s collection of Far-Eastern objects in Hauteville House, two introductory observations are necessary. First, not all the objects in the house date from Hugo’s time. Detailed cataloguing of the contents of the house in currently underway (the results are published on https://www.parismuseescollections.paris.fr/fr) and when completed, it will give a clearer idea of which objects were collected by Hugo himself and which were added after his death. Second, Hugo was an unsystematic collector with little in-depth knowledge of Asian art, who seems to have valued the objects he acquired primarily for their decorative possibilities. Many of the objects in the house, especially among the ceramics, are Western imitations. Hugo was certainly aware that this was true for some, but perhaps not for all. The systematic study of all objects, part and parcel of the cataloguing of the collection, will shed more light on the place of origin of many of the objects of the house. A current curatorial estimate is that the objects manufactured in the Far East may number only around fifty.

Porcelains and ceramics, generally, form an important part of the décor in Hauteville House. They comprise mainly tableware, such as plates and tureens, but also numerous vases and figurines. Many pieces are found in the first-floor couloir aux faïences, where they are fixed to the walls and the ceiling; in addition, tureens, vases, and figurines are placed on tables and cabinets all through the house, but especially in the red and blue salons on the second floor, where, together with Chinese painted wallpapers, lacquered cabinets and silk upholstery they contribute to creating an outlandish and festive atmosphere suitable to the rooms, which were used for parties. A pair of famille rose medallion vases, currently in the blue room are typical of the 19th-century Chinese export art that Hugo collected. Around the neck are animal and plant motifs modeled in relief while painted “medallions” on the body depict narrative scenes. Another pair of famille rose vases, also in the blue room, is decorated with dragons and auspicious patterns. Such vases were often created as blanks in Jingdezhen, then transferred to Canton, where the decoration was added according to foreign customers’ request, hence the alternative for such wares, Guangcai (Cantonese Color). Hauteville House features several Japanese Imari pieces, including a large round dish in the dining room. Named after the port through which it was exported, Imari ware was made in Arita from the end of 17th century onward and widely exported in the first half of 18th century at a time when the Chinese exported little porcelain due to political turmoil. Painted in underglaze blue, with overglaze enamels and gold, Imari ware was so popular that even the potters in Jingdezhen often copied it after they restarted manufacturing. Among the Chinese-inspired pieces made in 19th-century Europe are some Willow Pattern plates created by 19th-century English potters using transfer-printing in underglaze blue (Portanova J., [n.d.]). A set of early 19th-century Mason ironstone dishware (Roberts G., 1996, passim), including two tureens (billiards room) and plates (corridor aux faïences), is another example of Chinoiserie. It is copied after Chinese Mandarin ware, famille rose export porcelain created at the end of 18th century, depicting joyful Chinese family life, often with a man in official mandarin costume of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) accompanied by his wife and, sometimes, his children. The set in Hugo’s collection was obviously not made in China judging by the European faces, the incorrect depiction of the costumes and the perspective rendering of the railing in the background. In addition to dishware and vases, Hauteville House also features numerous ceramic and porcelain figurines, such as the pair of turquoise Foo dogs in the Red Salon, four women holding vase above the door of the dining room, and a blanc de chine Guanyin holding a boy, indicating she is a son giver, in the billiards room.

A period photograph shows that the Guanyin figure originally stood (as it still does today) between the two Mason tureens of family life (see above) and a pair of famille rose vases with scenes of the Taoist deity Magu giving offerings to Longevity (Hauteville House Guide, 2019, p. 28). Such a combination would have had visual resonance in Chinese culture, where family, sons, and long life were highly desirable. This raises the possibility that Hugo was not merely interested in the decorative aspects of the objects he collected but also in their cultural meaning. Another popular form of East Asian export art was lacquerware. Hugo’s collection comprises a set of red lacquer doors, see below) brought over from his apartment in the rue de la Tour d’Auvergne in Paris (Hauteville House Guide, 2019, p. 35), several lacquer cabinets of different sizes, a folding table, lacquer boxes, and a lacquer version of an ancient bronze Fang (wine vessel). Most lacquer pieces appear to have been made in China though some may be Japanese. These pieces show several specific lacquer techniques, such as painting, carving, and inlay.

The Red Salon side of the double doors connecting the Red and Blue Salons is paneled with two sections of a red lacquer screen delicately painted with gold and silver. One of the most elaborate pieces in Hauteville House is a Coromandel lacquer cabinet in the billiard room. Like many cabinets of its kind, it may have been fabricated in Europe out of lacquer screen panels originally made in Yangzhou or Canton for export via the Coromandel Coast of India. Coromandel lacquer is characterized by the use of many coats of lacquer, which may be incised, painted, and/or inlaid with other materials. Various forms of Chinese paintings are found all over the house. Painted bamboo blinds are fixed on the wall near the entrance as decoration while hand-painted (ink and watercolor) wallpaper with flowers and birds decorates the ceiling. Translucent panels printed on silk are found in the atelier-fumoir, where they are used to dim the light coming through the windows. On the first floor, part of the Blue Salon features more hand-painted Chinese wallpapers, showing figures in landscapes or gardens painted in saturated colors and showing an obvious interest in Western perspective. Such papers were key elements in 18th-century “Chinese rooms”. The same artists who painted wallpapers also painted on silk, panel or canvas. The Blue Salon side of the double doors connecting the two Salons appears to be painted in oils on panel and shows scenes that are similar in style to the wallpaper. Large scale textiles are used to decorate the Red and Blue Salons rooms in a magnificent style, such as the, probably European damask on the walls (restored) and the oriental style beaded tapestries made in Europe, which cover the walls and ceilings. In the Red Salon, there are two sets of Chinese embroidered silk: one is the canopy over the fireplace, another set covers a set of doors and an elaborate lambrequin above it. The latter is embroidered with small figures wandering among willows and flowering trees. To date, no trace has been found in Hauteville House or elsewhere of the “lot de soieries de Chine vendu par un officier anglais qui était de l’expédition et qui l’a pris au palais d’été de l’empereur de la Chine,” mentioned in Hugo’s Agendas on March 23, 1865 (Hugo V., Œuvres complètes, vol. 12, 1969). Not all the pieces in Hauteville house are Chinese export art, strictly speaking. The egg-shaped brass incense burner (see above) enveloped by peach branches and fruit seated on a carved wooden base in the center of the Blue Salon was not especially made for export, though objects of this kind did find their way to Europe regularly. The same is true for the carved and gilded Buddha (see above) seated on a wooden throne, likewise in the Blue Salon, which demonstrate that Europeans were not only interested in export art but also bought objects made for the Chinese market.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne