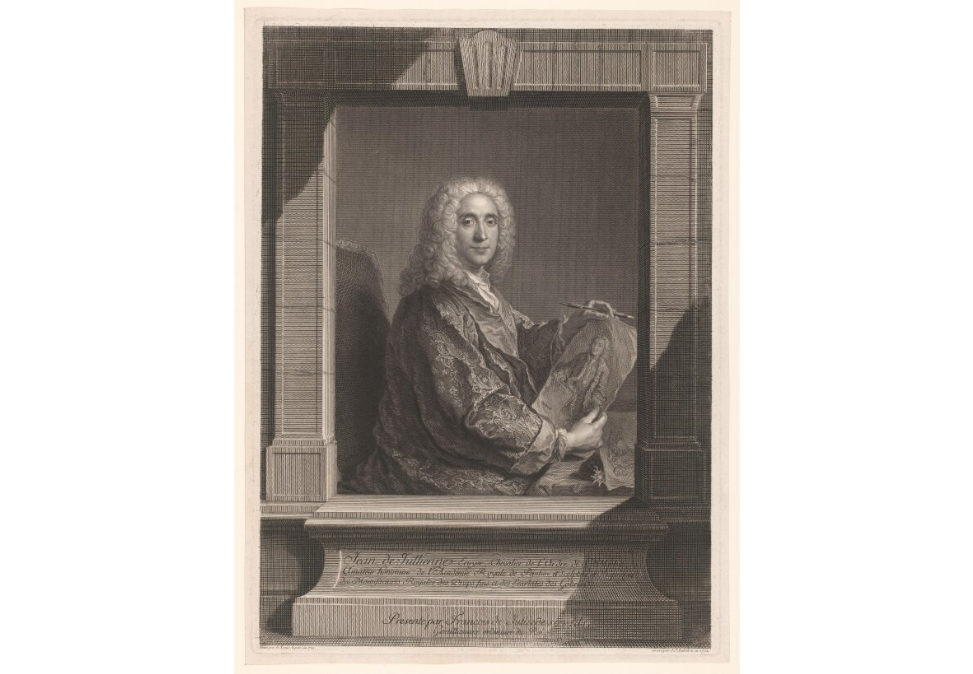

JULLIENNE Jean de (EN)

Biographical article

Jean de Jullienne was born in Paris on 29 November 1686, as the son of Claude Jullienne de Francœur, a linen merchant (died before 1720), and Anne Daniel (birth and death dates unknown). His godfather was Jean Glucq (?-1718), who in 1674 married Jullienne’s father’s sister, Marie-Charlotte Jullienne (?-1723). Born in Amsterdam, Jean Glucq moved to Paris in 1667, when Colbert (1619-1683) called on him to found a dyeing manufactory at the Gobelins, thanks to a privilege granted for the bleaching of woollen fabrics and dyeing cloth scarlet, red, crimson, purple, and green in the Dutch style. François Jullienne (1654-1733), his wife’s brother, joined him shortly afterwards at the Gobelins, and was granted the privilege of establishing the Manufacture Royale de Draps Fins, specialising in fine linen in the Spanish, English, and Dutch styles. The two manufactories specialised in two complementary métiers and their success enabled Jean Glucq to retire from the textile trade. When he died in 1718, his two sons, Claude Glucq (?-1742) and Jean-Baptiste Glucq (1674-1748) de Saint-Port, transferred the privileges endowed to them to François Jullienne.

The history of Jullienne’s relatives is that of exceptional social mobility in the eighteenth century. Jean Glucq’s two sons held high positions in public office, and his son-in-law, Montullé, became head of Prince Louis-François de Bourbon’s council. When he went to live with his uncle Jean Glucq, probably circa 1700, Jean de Jullienne entered the world of the Gobelins, where he remained for the rest of his life. He received his journeyman’s certificate in dyeing on 6 April 1712, and was received into the guild as a master dyer on 9 August 1719, at a time when the Law System made it possible to obtain this type of certificate by means of a payment, without going through any training. It is also difficult to imagine that Jean Glucq did not provide his nephew with any general training in the métier. The highly prised seven hundred volumes in the inventory made after his death provide a more nuanced image of the merchant and collector, and make it possible to refute any assumptions that the collection was assembled by someone who was not interested in literature (AN, MC/ET/XXIX/529).

In 1721, his uncle François Jullienne associated him in the privileges granted to him and retired from the business in 1729, leaving him to manage the manufactories. In 1738, Jean-Baptiste Glucq de Saint-Port, who acquired his brother Claude Glucq’s share of the inheritance for cash, sold the two manufactories, houses, and inheritance to Jean de Jullienne, who then renounced his right to work as a master dyer on 22 October and reserved the right to exercise the privileges granted by the king. The success of the manufactories was such that Jean de Jullienne was knighted in September 1736 (AN, Z 1A.597; BNF. Cabinet des Titres, Nouveau d’Hozier, 196). The granting of letters patent — they conferred an inalienable legal status on a person or corporation — was the highest form of honour, the crowning achievement of a career and reputation as a merchant. Sixteen years earlier, on 22 July 1720, Jullienne had married Marie-Louise de Brecey (1697-1778) (AN, MC/ET/XXIX/349).

Although the marriage was financially advantageous, it was not a noble marriage. They had four children, three of whom died at a young age. The signatures of Louis de Bourbon, the Comte de Clermont, and Victor Amédée de Savoie, Prince of Carignan — princes of royal blood — on documents relating to the marriage of his son François de Jullienne (1722-1754) with Marie-Élisabeth de Séré de Rieux (1724-1799), confirm Jullienne’s elevated social status. François de Jullienne passed away on 21 June 1754 without an heir; his widow died in 1799 and, with her passing, Jean de Jullienne’s direct line ended at the end of the century. Although Jean de Jullienne owed his career as a merchant at the Gobelins to his uncles Jean Glucq and François Jullienne, he owed his entry into the nobility to his cousins, Jean-Baptiste Glucq de Saint-Port and Claude Glucq, and, by marriage, Jean-Baptiste de Montullé (?-1750), who in 1714 married Jean Glucq’s last daughter, Françoise Glucq (?-1730). In 1764, Jean de Jullienne transferred the ownership, management, and running of the manufactories, as well as his property, to their eldest son and his nephew, Jean-Baptiste François de Montullé (1721-1787).

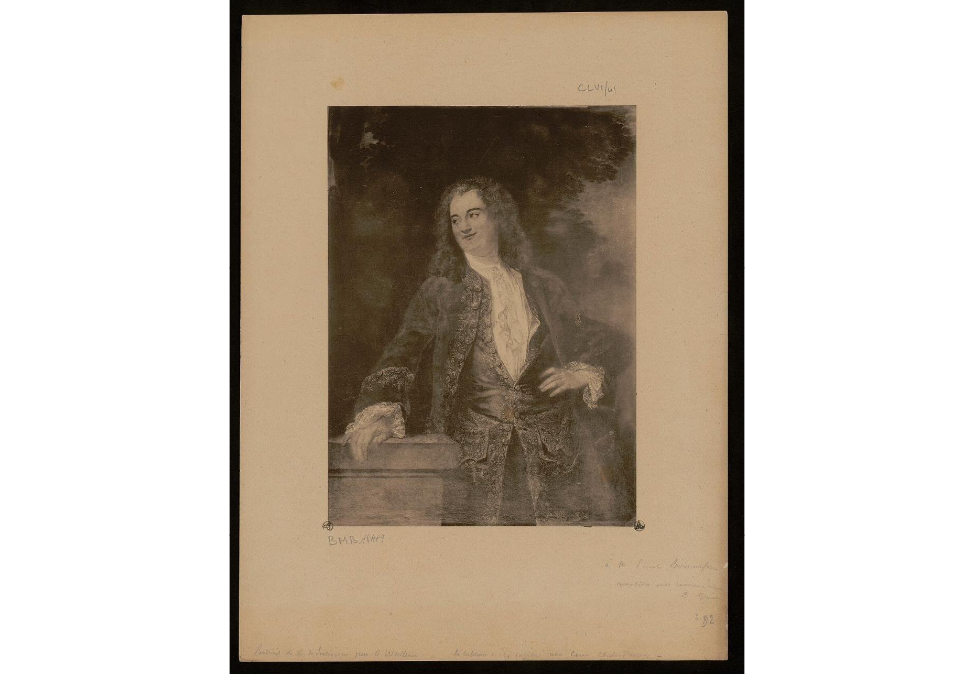

The Gobelins was a bustling centre for research and learning that inspired emulation, and a place where people met, bringing together the painters and draughtsmen who worked at the Gobelins, as well as the artists and engravers who worked for the king and who were members of the Académie, and who lived there. Most of the painters whom Jullienne commissioned, whose works he collected, and whom he involved in his projects, worked there. By working with them, he acquired knowledge that was unique for a collector in the eighteenth century. At the same time, he became acquainted — thanks to his cousins Claude Glucq, Jean-Baptiste Glucq de Saint-Port, and Jean-Baptiste de Montullé — with the circle of enthusiasts and collectors surrounding the Comtesse de Verrue (1670-1736), her son-in-law, Victor Amédée de Savoie, Prince of Carignan (1690-1741), and her friends Armand Léon de Madaillan de Lesparre, the Marquis of Lassay (1652-1738), Louis Auguste Angran, the Vicomte de Fonspertuis (dates? 1669-1747), Antoine de La Roque (1672-1744), Jean-François Leriget de La Faye (1674-1731), Germain Louis Chauvelin (1685-1762), and Charles Jean-Baptiste Fleuriau, the Comte de Morville (1686-1732). It was in this pioneering circle that he became acquainted with Dutch and Flemish art, forged close ties with the artists of the Académie, and proceeded to have engravings made of Antoine Watteau’s drawings and paintings. On 31 December 1739, Jullienne offered four books of prints made after Watteau’s drawings and paintings to the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, which in turn appointed him Conseiller Honoraire et Amateur (Montaiglon A., 1875-1892, Vol. V, pp. 264-265). His career as a collector is relatively unique, because he moved from the private to the public sphere of art. The origins of Jullienne’s collection are thus multiple and complex. However, there are two reasons for the collection’s distinctiveness: he was the first collector who wished to enter the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, before this was seen as prestigious or socially desirable, and his collection became famous enough for it to be sold at auction at the Salon Carré, between March and May 1767. (Rémy, P., Julliot, C.-F., 1767.)

The collection

According to Edme François Gersaint (1694-1750) and Jean-Aymar Piganiol de La Force (1669-1753), Jullienne started his collection around 1715, when he undertook translating drawings by Watteau (1684-1721) into engravings. The two volumes of Figures de différents caractères, containing the prints engraved after the drawings, were advertised in the Mercure de France in November 1726 and December 1727. He wrote an Abrégé de la vie d’Antoine Watteau, Peintre du Roy en son Académie de Peinture et de Sculpture as an introduction — the fifth biographical text devoted to the painter. In July 1727, he secured the exclusive privilege — a privilege that extended for ten years — to reproduce all the paintings by Watteau in his possession. Thirty-nine paintings by Watteau were engraved and carried the inscription ‘from the cabinet of M. Jullienne’, which only contained eight works in 1756. The two-volume L’Œuvre d’Antoine Watteau Peintre du Roy en son Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture gravé d’après ses tableaux et desseins originaux tirez du Cabinet du Roy et des plus curieux de l’Europe par les soins de M. de Jullienne was published in Paris between 1734 and 1736.

Jullienne assembled his collection gradually, and his activity as a collector endured for almost forty years, while for others it was merely an ephemeral pursuit. The evolution of forms in art throughout the eighteenth century is thus inherently linked to the development of his collection, which alone provides insight — thanks to the three sources available to us: the illustrated catalogue, the inventory of his estate, and the sales catalogue — into the movement of the works of art in a collection. In its various forms, Jullienne’s collection contained around five hundred paintings from the French, Italian, Spanish, Flemish, and Dutch schools, and 2,300 drawings, gouaches, and pastels, bound volumes of studies and sketches, and prints and sculptures. The quality of a collection depends on its capacity to be disposed of. It is not a question of scaling down the assembled ensembles, but renewing them, like reworking a canvas. The collection’s heterogeneity stems from a continual process of development, which is sometimes linked to earlier works, but above all to works from the period to which it is devoted, and from which it draws its significance, as Jullienne’s collection was assembled through his close contacts with living painters. The Catalogue de tableaux de M. de Jullienne, a handwritten inventory, of which a single copy was drawn up circa 1756, presents the collection during its author’s lifetime, at a time when it was available to be viewed and visited, and was constantly evolving. The forty-two plates of pencil drawings, watercolours, and gouaches show the arrangement of the works, as they were presented to visitors, from one wall to the next, according to their location in the various apartments of his house at the Gobelins.

Upon Jullienne’s death in 1766, Claude-François Julliot (1727-1794), a jewellery merchant at the Curieux des Indes, was responsible for evaluating his curiosities and advertising them in the sales catalogue published after that of the paintings, drawings, and prints compiled by Pierre Rémy (1715-1797). The curiosities, sold one by one at auction, in the same way as the paintings and according to Jullienne’s wishes, were dispersed and are now rarely identifiable. Boulle furniture, bronzes, Egyptian vases in green basalt, porphyry, and Sicilian marble vases, busts and antique marbles, contemporary terracottas, objects made of amber, ivory, crystal, and silver from the Indies were combined with 107 pieces of European porcelain, from the Saxe, Sèvres, Chantilly, Saint-Cloud, and Villeroy manufactories, 750 oriental porcelains from China and Japan, of which only 209 were mounted, that is to say less than a quarter of them, lacquered objects from Japan and Coromandel with a black ground, girandoles, coloured hard- and soft-paste porcelains from the Indies, beautiful purple Persian ceramics, and two Chinese lanterns. The porcelains included very fine ancient single-colour pieces, in celestial blue, light turquin blue, antique Japanese white, and celadon, as well as coloured pieces, in blue and green on a grey ground, yellow and splashes of brown, red or marbled green, mottled green or gilded, on a crackled grey ground with jasmine blue and white or jasmine white in relief, blue and gold with cartouches with a white ground, decorated with dragons, farmland criss-crossed by hedges and trees or foliage, pagodas, porcelain wares adorned with decorations inspired by Chinese vases, and so on.

The number and diversity of the assembled works made it more difficult to define them and identify any links between them. Jullienne grouped pieces and works together according to perceived characteristics, insofar as he identified links and similarities, and highlighted comparisons. Exhibiting objects of Asiatic and European origin in a specific setting gave them a market and symbolic value, and thus contributed to changing people’s perception of them, and, as a result, their appraisal. Transforming an object also changes the sensation it gives rise to through the two senses that are stimulated: vision and touch. Exhibiting paintings, sculptures, furniture, and curiosities that are intact or that have been transformed in the same room makes them all equally interesting as objects of contemplation and interest, and which promote reflection. In reality, this ensured that the objects conveyed meaning and held appeal. The sale of the collection took place at the Salon Carré in the Louvre. This had never happened before and never occurred again. For the first time, the king agreed to allow the area that had been reserved for Académie Royale exhibitions since 1725 to be used for an auction. ‘Never has it been so furious’, wrote Johan Georg Wille (1715-1808). Bringing together ‘Tout Paris’, the upper crust of Parisian society, and European royal officials, it was the only collection that was dispersed in a royal palace, which shows how Jullienne had succeeded in increasing the symbolic value of pieces whose status was still uncertain in the world of design — oriental pieces that were henceforth more than just exotic objects or ornaments of convenience. Although the sale of his collection endowed the objects he had assembled with a certain prestige, it also highlighted his accomplishment as a collector. Jullienne’s uniqueness lies in the fascinating fact that the collection was dispersed after his passing. Herein lies all the ambiguity of the paradigm he embodies.

Domaine public / CC BY-SA 3.0

Related articles

Oeuvre / objet civil domestique

Oeuvre / objet civil domestique