VEVER Henri (EN)

Biographical article

Henri Vever was born in Metz on 16 October 1854 into a family that had worked as gemstone artisans and jewellers (bijoutiers-joailliers) for two generations. The family moved to the capital in 1871, where Ernest bought the collection owned by the bijoutier Baugrand, located at 19, Rue de la Paix. In 1871, Henri Vever began an apprenticeship with the bijoutiers-joailliers Loguet, then Hallet, and attended courses at the École des Arts Décoratifs. Two years later, he was admitted to the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts and joined the studio of Jean-Léon Jérôme (1824–1904).

In 1881, Ernest Vever transferred the management of the family business to his two sons, Paul and Henri Vever, with whom he had been collaborating since 1874. The eldest of the two, Paul, having graduated from the École Polytechnique, took over the administrative management, while Henri was in charge of the company’s artistic orientation, which he managed until 1921. The Maison Vever began to participate in the Expositions Universelles in 1878, and in 1889 was awarded one of two major prizes attributed for jewellery. In 1891, it participated in the French exhibition in Moscow and was regularly awarded prizes for its many participations in national and international exhibitions (INHA).

In 1885, to satisfy his passion for French painting, Henri Vever purchased works from Paul Durand-Ruel (1831–1922). They included canvases by painters from the School of 1830: Jean-Charles Cazin (1841–1901), Jean-François Raffaëlli (1850–1924), and Corot (1796–1875), including Wounded Eurydice (cat. no. 20) and Route ensoleillée(cat.no. 26); and the Impressionist masters, comprising nine works by Monet (1840–1926), including Sainte-Adresse (cat. no. 79) and La Berge, à Lavaucourt (cat. no. 83), Alfred Sisley (1839–1899), and Camille Pissarro (1830–1903), as well as Ludus pro Patria (cat. no. 92) by Puvis de Chavannes (1824–1898). His collection, comprising 188 pictures and sculptures, was sold in February 1897 by the art dealer Georges Petit (1856–1920), complemented by a richly illustrated and luxurious catalogue.

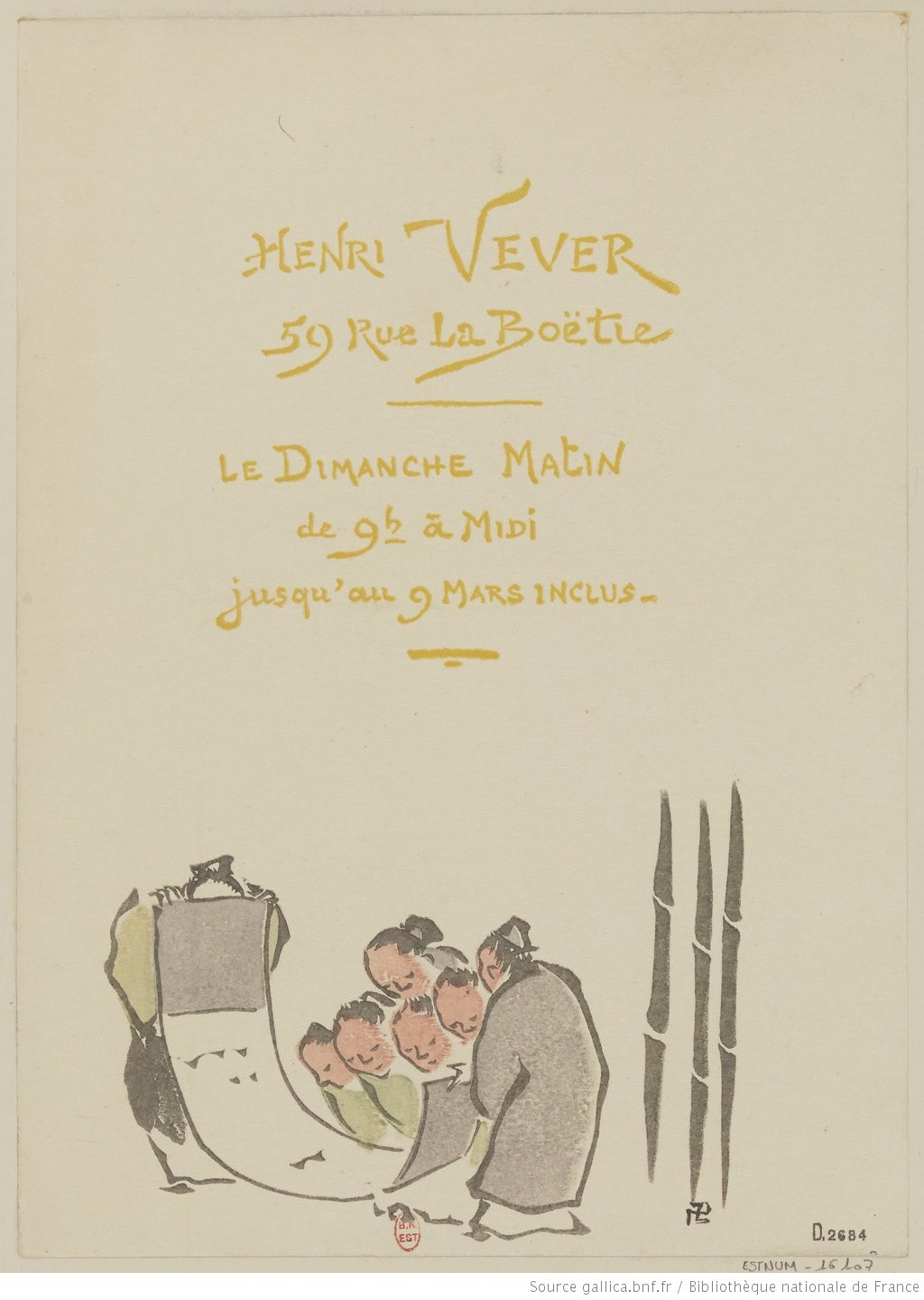

In 1892, Henri Vever began to regularly attend the almost monthly dinners held by the Amis de l’Art Japonais, established by the art dealer Siegfried Bing (1838–1905) as part of his campaign to promote Japanese art (Koechlin, R., p. 21). Here, he met fervent Japanese ‘bibeloteurs’ (collectors of knick-knacks)—to borrow the expression of Edmond de Goncourt (1822–1896)—, such as Charles Gillot (1853–1903), Hayashi Tadamasa (1853–1906), Hagiwara (?–1901), Michel Manzi (1849–1915), Gaston Migeon (1861–1930), Raymond Koechlin (1860–1931), Raphaël Collin (1850–1916), Lucien Lévy-Dhurmer (1865–1953), and Camille Groult (1832–1908), who would meet at the Café Riche, the Café Cardinal, or at Véfour’s. The invitation cards for these diners were illustrated—at least until 1914—by the likes of Jules Chadel (1870–1941), Prosper Alphonse Isaac (1858–1924), and George Auriol (1863–1938), who created engravings resembling Japanese woodblock prints, with hand-printed colours on Japan paper (Département d’Estampes et Photographie, BnF,); these gatherings lasted until 1942, thanks to Henri Vever, who took over Bing’s role upon his death in 1905. In 1892, he had also become a correspondent member of the Japan Society in London through the intermediary of Siegfried Bing.

In December 1897, Henri Vever was made a Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur. And the following year, he presided over the sub-committee responsible for organising the Exposition Centennale Rétrospective, in anticipation of the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. The Maison Vever was also awarded a Grand Prix at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900 (AN (French national archives) 19800035/260/34601), where twenty pieces of Art Nouveau jewellery—created in collaboration with Eugène Grasset (1845–1917)—attracted much interest. He was a member of the Conseil de la Société Franco-Japonaise when it was established in 1900.

In 1904, Henri Vever was appointed Vice President of the admission committee, Group 31 (gemstones and jewellery at the Saint-Louis World’s Fair, USA).

The following year, he was elected a member of the Board of Directors of the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs, a post he held until 1919.

Between 1906 and 1908, he focused on the publication of the three volumes of LaBijouterie Française au xixe siècle.

He introduced for the first time in the West Japanese art as an artistic force in the creations of the Maison Vever, working mainly with Eugène Grasset (1845–191) and René Lalique (1860–1945). For Henri Vever, Japan represented—as it did for other connoisseurs of Japanese art such as Henri Bouilhet (1830–1910) and Charles Christofle (1805–1863)—a renewal of forms and motifs thanks to a new source of inspiration. He noted that ‘it is not as models that these [Japanese] works have been the most useful; they have, above all, the very precious advantage of encouraging us to make direct contact with Nature, which we have neglected, since the Middle Ages’ (Vever, H., 1908, p. 759); he also noted that ‘far from imitating more or less slavishly, the Japanese [artists] are solely inspired by their general composition and layout’ and maintain ‘a preponderant element of personal invention and merit’ (Vever, H., 1911, p. 111).

In 1924, he donated his collection of 350 items of jewellery—sixty of which came from the Maison Vever—to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

The following year, he was made a ‘grand donateur’ of the Musée du Louvre, then a member of the Conseil Artistique des Musées Nationaux in 1930.

He was promoted to the rank of Officier de la Légion d’Honneur in October 1938 (AN (French national archives) 19800035/260/34601). He passed away in his Château de Noyers (in the Eure département) on September 23, 1942.

The collection

An insatiable collector, Henri Vever spent his whole life indulging in his various passions for old Western paintings and engravings, coin collecting, books, Persian miniatures, Japanese and Chinese objects, and, of course, jewellery.

Henri Vever, a fanatical connoisseur of Japanese objects

‘(…) I cannot resist when it comes to objets d’art … it is my mea-culpa’ he wrote in his Journal on 21 August 1898 (Silwerman, W., 2018, p. 247).

As a member of the second generation of connoisseurs of Japanese art (Koechlin, R., 1930, p. 2), his passion may have begun during the 1878 Exposition Universelle, in which the Maison Vever participated, while Japan was represented in the retrospective section. His passion developed further in the 1880s, when—after the fashion for reasonably priced ornaments and the first brightly coloured engravings had passed—Hayashi and Bing oriented the market towards ancient woodblock prints and eighteenth-century ‘brocade’ prints (nishiki-e) directly imported from Japan. In their wake, followed curious and wealthy connoisseurs. The fashion for ‘japonaiseries’ was already underway in 1883 when Louis Gonse (1846–1921) held the exhibition ‘L’Art Japonais’ in the Galerie Georges Petit with 3,000 objects from private collections listed in the catalogue, and published L’Art Japonais.

That year, Bing opened a new shop at 19, Rue de la Paix, in the very building that housed the family and the Maison Vever.

The relations between the two men can be retraced with certainty to 1888, because an invoice dated 15 December 1888 from Siegfried Bing made out to Vever concerned the purchase of nineteen prints, an example of Hokusai’s ‘Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji’ and Hiroshige’s‘Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō’.

In his Souvenirs d’un vieil amateur d’Extrême-Orient, Koechlin wrote about the visits these connoisseurs made to Bing’s and Hayashi’s shops: ‘In a feverish atmosphere, Henri Vever made lengthy visits when he left his shop. Gonse and he were the only clients allowed to see the crates being unpacked in the basement of the shop on the Rue de Provence’, while many specialists on Japanese objects, including Vever, were invited to the diners held by Bing in his apartment on the Rue de Vézelay, where they were able to admire his private collection (Koechlin, R., pp. 21 and 22).

Forty-nine letters from Vever sent to Hayashi Tadamasa and his brother, Hagiwara, written between 1893 and 1906, mentioned the collector’s communications, purchases, and settlementssometimes with deals—relating to objets d’art. This correspondence reveals the special relations between the two men and Vever, who had an account with Hayashi, and who asked to be the first to see his discoveries, as mentioned by Edmond de Goncourt: ‘(…) Vever the jeweller, the most passionate of all and who showed us the ticket for his place on the ocean liner for the Exposition he intends to visit [the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, Chicago]. He will surprise Hayashi and will take the best of the Japanese prints, which he will bring back to France after the Exposition’ (Goncourt, E., 1956, p. 366).

He asked Tadamasa and his brother Hagiwara to help display his prints, set up his workshop, and draft the catalogues for his collections and the notes about Chinese and Japanese jewellery, and in 1898 create a Japanese cachet of his name (Correspondance adressée à Hayashi Tadamasa, 2001, p. 258). In return, Vever was Hagiwara’s testamentary executor, the ultimate proof of the reciprocal trust and respect between Vever and Hayashi’s family, not to mention the commercial links between them; they sometimes shared the same clientele.

The extent of his financial means and his relations with Bing and Hayashi enabled him to see and select—before the other japonisants (connoisseurs of Japanese art)—objects from the finest ‘arrivals’ from Japan.

In just ten years, between 1882 and 1892, Henri Vever managed to compile, both in quantity and quality, one of the largest and finest collections of Japanese prints in Paris: ‘His collection of illustrated books and colour prints is certainly the finest and largest that has ever been amassed’, wrote Henri Rivière (1864–1951) (Rivière, H., 2004, p. 105).

He frequented, amongst the most prominent connoisseurs of Japanese art, Raymond Koechlin, a foreign policy journalist at the Journal des débats (1887–1902) and a member of the Conseil de l’Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs (1899), Gaston Migeon, an assistant librarian in the Musée du Louvre (1889–1893) who subsequently worked in the Département des Objets d’Art (1893–1899), and Charles Gillot,whom he saw regularly. He appreciated the simplicity of his character and the pertinence of his choices. As a printer and engraver-lithographer, Bing appointed Charles Gillot as director of LeJapon Artistique. The latter belonged, like Vever, to a class of entrepreneurs that came from the bourgeoisie and who had an artist’s temperament, forming a group of artisans who were passionately interested in japonisme, as well as the art publisher Michel Manzi (1849–1915), and the painters and engravers Henri Rivière and George Auriol (1863–1938).

Through the diversity of his taste in ‘japonaiseries’, in the words of Champfleury, Gillot probably introduced Vever to other objects of interest: sabre guards (tsuba), vases, writing desks (suzuki bako), bronzes, lacquered objects, fans, and textiles.

In the workshop on the Rue La Boétie and the workshop established in the district of the Chaussée d’Antin as of 1895, the decor was intended to be a showcase for the Japanese and Islamic collections. A veritable place of sociability, Vever entertained his friends there, surrounded by netsukes (miniature hand-carved sculptures), pottery, bronzes, screens, and Japanese prints. A letter that he sent to Hayashi Tadamasa attests to the care with which he presented these objects, requesting that he procure him: ‘Pieces of ancient fabric for the panels in the library in subdued and harmonious tones’ (Correspondance adressée à Hayashi Tadamasa, 2001, p. 258).

Robert de Montesquiou’s dedication in Les Paroles diaprées paid tribute to the man and his collections:

‘You have bronzes, lacquered objects,

Enamels, kakemonos,

Foukousas abounding in macaques,

And albums full of sparrows.

You have wood, ivory,

Inrōs and Tchaïrés;

And your showcases, your cupboards

Are overflowing with sacred toys.

You will therefore read this book,

Which, at least, has the merit

That, in places, is brought to life,

A little of the soul of Japan’

(Wilfried Zeisler, ‘Notice Vever’, Dictionnaire critique des historiens de l’art actifs en France de la Révolution à la Première Guerre mondiale, INHA (online)).

Henri Vever, a generous lender

In 1890, he took part in the first exhibition in France devoted to Japanese engraving, organised by Bing at the École des Beaux-Arts. Vever was on the organising committee along with Philippe Burty (1830–1890), Edmond de Goncourt, the painter Charles Tillot (1825–circa 1886), a friend of Degas, E. L. Montefiore, Charles Gillot (1853–1903), Georges Clemenceau (1841–1929), Antonin Proust (1832–1905), and Edmond Taigny (1828–1905). Seven hundred prints and illustrated books were listed in the catalogue—half of the loans came from Bing—and Vever loaned seventy prints signed by draughtsmen who were well known at the time, such as Kiyonaga 鳥居清長 (1752-1815), Utamaro 喜多川 歌麿 (circa 1753-1806), Hokusai 葛飾 北斎 (1760-1849) or Kuniyoshi 歌川 国芳 (1798-1861).

Held between April and May 1890, the exhibition was praised as a complete success, even by the most sceptical of critics, such as Arsène Alexandre (1859–1937) and Raymond Koechlin, while it confirmed the artistic orientation of the Impressionist painters, which is mentioned by Pissarro in a letter sent to his son Georges: ‘I saw wonderful things at the Japanese exhibition’; and he described a kakemono by Kōrin: ‘monkeys sitting together on a branch, it is truly admirable—simply a tree branch with leaves and sitting monkeys’ (Correspondance de Camille Pissarro, 1988, letter 589).

In 1892, for the fifth ‘International Black and White Exhibition’, followed in 1902 by the ‘Exposition de la Gravure sur Bois’ (‘Exhibition of wood engraving’) at the École des Beaux-Arts, which presented a panorama of Western and Eastern work, Vever, no doubt at Siegfried Bing’s request, loaned for the first exhibition 227 Japanese woodblock prints (Bing 149 sheets) and, for the second, a collection of so-called primitive (beginning of the eighteenth century) Japanese books.

Without attempting to be exhaustive, we should mention amongst the most important exhibitions of Japanese art, those held by the Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs—under the direction of Raymond Koechlin—between 1909 and 1914, devoted to Japanese prints. Sixty-six exhibitors responded to the call, including the ever-loyal Vever as a contributor. These annual exhibitions, which never lasted for more than month, presented the general public with a century of Japanese prints, from the middle of the seventeenth century to 1850. Two thousand three hundred and eighteen sheets were displayed to the visitors, including 523 from the Vever Collection. Luxurious catalogues contained one hundred black and white reproductions and ten colour plates.

Henri Vever opened his boxes for the exhibitions and authorised the reproduction of his collection in journals and works by his contemporaries, and even drafted the prefaces in their works.

The establishment of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in 1905 provided an opportunity to celebrate Japan again and Henri Vever actively participated in the exhibitions: Japanese textiles in 1906, Japanese sabre guards in 1910, sabre and inrō decorations in 1911, Japanese lacquered objects the following year, and, in 1913, Japanese masks, netsukes, and small sculptures.

Henri Vever, a zealous donator

When Gaston Migeon decided in 1893 to create a Japanese section in the Musée du Louvre—but without the financial means to do so—, he appealed to the generosity of the faithful Japan connoisseurs, Koechlin, Rouart, Manzi, Gillot, and Vever. They gave him around fifty prints for his project. For the latter this was a consecration, an institutional recognition of amateurs and the consecration of Japanese prints as part of the cultural heritage. Prints from the collector’s cabinet were now considered works of art. Vever carefully selected around thirty prints that covered the evolution in the art of woodblock prints, from black and white works, which were relatively unknown (mid seventeenth century), to nishiki-e prints illustrated by Harunobu, Shunshō, Kiyonaga, Utamaro, Shunman, Eishi, Chōki, Shunkō, Shunei, Hokusai, Sharaku, and Hiroshige, and nineteenth-century prints by Kuniyoshi. The varied themes—a woman with child, and Utamaro’s courtesans, the views of Fuji and Hokusai’s birds—attest to the care taken by Vever to familiarise the general public with this subtle art.

And in 1905 he also made a donation of thirteen Japanese woodblock prints to the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, which was based in the Pavillon de Marsan, in complement to the 1894 donation to the Musée du Louvre, comprising prints by Harunobu (inv. no. 12121, inv. no. 12117), Kiyonaga, Shunman (inv. no. 12120), and Hokusai (inv. no. 12124), as well as eight by Hiroshige, a draughtsman whose work was almost absent in 1894, with representations of landscapes, birds, and fish. In 1912, he donated to the Musée Guimet a triptych by Shunshō (inv. no. EO 1457) and the famous Self-Portrait as an Old Man by Hokusai drawn in ink, a gift from Siegfried Bing and previously certified as having been executed by Hayashi (inv. no. EO 1456). Lastly, the right-hand sheet of the triptych A Scene on the Bridge by Utamaro (inv. no. EO 2591) and the eight-leaf screen on paper by Hokusai enriched the institution’s collection.

In 1920, Henri Vever parted with part of his collection of Japanese prints, which went to the businessman Matsukata Kōjirō (1865–1950). The son of Matsukata Masayoshi (1835–1924), twice minister between 1891 and 1896, Kōjirō was the managing director of a powerful company that specialised in industrial equipment and maritime transport (now called Kawasaki Heavy Industries). This collection compiled by Henri Vever comprised around 2,000 sheets that represented Japanese prints according to different periods, executed by the most famous draughtsmen and with a variety of subjects. It constitutes the collection of Tokyo’s Museum of Western Art, which in 1925 published a catalogue in Japanese by selecting, as was customary, 100 masterpieces; the stamps of Hayashi and Wakai feature on certain articles.

After the death of Henri Vever, his collection of Japanese and Chinese objects (inrōs, suzuki bako, various boxes, combs, various lacquered objects, weapons, netsukes, masks, ceramic wares, bronzes, cloisonné enamels, woodcarvings, helmets and masks, sculptures, screens and paintings, showcases, fabrics, books on the arts, sword guards, kozukas (small utility knife inserted in one side of the sheath), and sword fittings) was dispersed in 1948 at the Hôtel Drouot in three sales.

It was long thought that Henri Vever had sold all of his Japanese prints to Matsukata. Yet, three public sales in London, organised by his heirs in 1974 (382 lots), 1975 (284 lots), and 1976 (299 lots), and a last but slightly smaller sale in 1997, highlighted the richness and extent of this exceptional ensemble.

Benefiting from the discoveries of the first Japan connoisseurs and trained by the main actors in the market for Japanese goods, Vever—over these decades—acquired, traded, donated, and substituted prints with the aim of attaining an exceptional print quality. In fact, this contributed to the redistribution of the major collections sold in public sales around 1890–1900: those of Burty in 1891, Goncourt in 1896, Hayashi in 1902, Gillot in 1904, and so on, and in the 1920s (in 1920 and 1921, that of Manzi, in 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, and 1927, that of Haviland, and that of Gonse in 1924), which again enriched his collection. In the sale catalogue (Vever II, 1975) devoted to Utamaro were listed thirteen prints of fine facture and in excellent condition that had been presented at the 1912 exhibition in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

Vever stamped his prints as of 1894, mentioning H. VEVER in a rectangular cartouche with rounded edges (Lugt 2491bis). At his request, Hayashi provided him in 1898 with a very rare Japanese stamp that featured his name. The monogram ‘HV’ was stamped on all the sheets of the London sales, which have now been dispersed around the globe (Lugt 1781a and b). For experienced collectors, these stamps are the guarantee of an astonishing quality, with a very high print quality, complemented by an exceptional state of conservation.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne