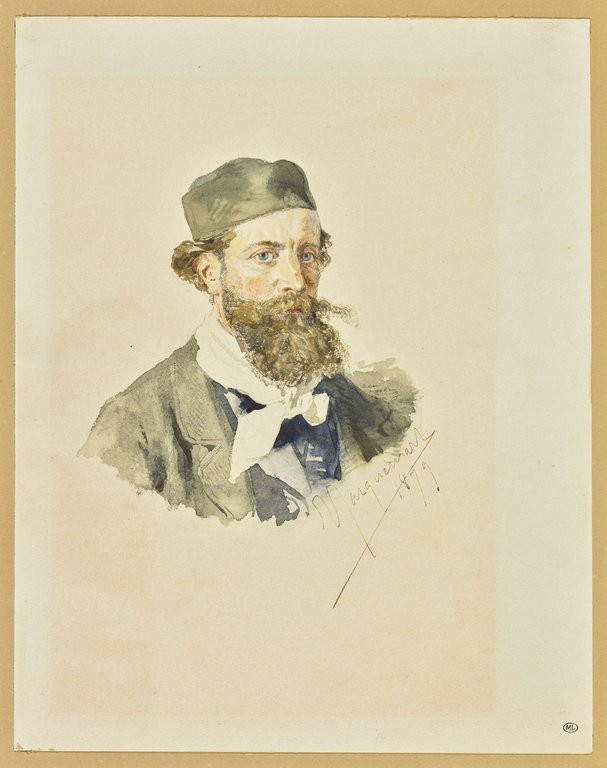

JACQUEMART Jules (EN)

Biographical Article

Jules Ferdinand Jacquemart (1837-1880) was one of the most renowned etchers of his time and a talented painter of watercolours. He was also recognised for his unique collection of shoes.

Early Years

Jules Jacquemart was born on September 8, 1837 in Paris (AP, V3E/N 1193). Son of ceramics collector and scholar Albert Jacquemart (1808-1875) and Louise Émilie Labbé (1813?-1884), he was the third of four siblings, his sisters Louise Pauline (1834-1885), Marie Louise (1835-?) who probably died young, and Marie Augustine (1844-1912) (D'Abrigeon P., 2019, p. 82).

The question of Jules Jacquemart's training remains mysterious. His artistic consciousness was certainly influenced by his father who may have studied at the École des Beaux-Arts and likely in the studio of Claude-Marie Dubufe (1790-1864) (D'Abrigeon P., 2019, p. 82), and his mother who, in her youth, executed drawings inspired by the works of Dubufe. According to Alfred Darcel (1818-1893), the father's works, in particular his watercolours painted for the Musée d’histoire naturelle, shared certain qualities with the etchings of his son: “There is the same precision in the drawing, the same accuracy in tone and the same feeling for the material” (Darcel A., 1875, p. 477). The student, however, exceeded his instructor, to the point of having Georges Duplessis (1834-1899) say that "in reality he had no master" (Duplessis G., 1880, p. 5).

Another important element of Jules Jacquemart's apprenticeship was his training in the uses of industrial design. His career would indeed have begun by drawing several compositions for a wallpaper (Duplessis G., 1880, p. 5) or carpet (Burty P., 1862, p. 2) company, although no work of this type has so far been found.

It was only then that Jules Jacquemart began to engrave, offering plates to his father who was struggling to find an illustrator of the artistic, industrial, and commercial history of porcelain (Jacquemart A., Le Blant E., 1862) (Duplessis G., 1880, p. 6). We do not know how he would have been introduced to etching, a technique still little used at the time (Bailly-Herzberg J., 1972 a., p. XIII-XIV). On the other hand, one finds in his library the Traité des manières de graver en taille douce by Abraham Bosse (1645), a technical reference manual which he would probably have used.

In 1859, Jules Jacquemart published his very first illustrations in the Gazette des Beaux-arts, first by providing a drawing for an article on the decoration of Chinese porcelain written by Albert Jacquemart and Edmond Le Blant (Jacquemart A. et Le Blant E., 1859, p. 65-75), then an etching for an article on Medici porcelain (Jacquemart A., 1859, p. 285). Probably introduced to publishers by his father, he worked for the magazine all his life.

His way of representing works of art, quickly noticed for its finesse and accuracy (Darcel A., 1861, p. 218), would make him a particularly appreciated illustrator and regularly solicited by several magazines: L'Art, the Gazette archéologique, and the Annales archéologiques.

Jules Jacquemart, Etcher

Alongside his contributions to the artistic press, Jacquemart produced various series of engravings, such as his Compositions de fleurs or old bindings for the Histoire de la Bibliophilie (Paris: J. Techener, 1861-1864).

He also regularly exhibited some of these plates at the Salon. For his first participation in 1861, he presented – in addition to two gouaches, Canard sauvage (Paris, musée du Louvre, inv. RF 2713) and Courlis (Paris, musée du Louvre, inv. RF 2392) – the etchings Les joies de la vie, three plates illustrating the Histoire de la Bibliophilie, and twenty etchings of porcelain from China and Japan taken from the Histoire de la Porcelaine (Sanchez P., Seydoux X., 2004, Salon de 1861, no 1617 -1618 and 3756-3758).

In 1865, the first part of Gemmes et Joyaux de la Couronne by Henri Barbet de Jouy (1812-1896) was published. These engravings of precious objects from the Galerie d’Apollon at the Louvre demonstrate an impressive virtuosity, systematically rendering of the texture, brilliance, and density specific to each material. This series, on which Jacquemart worked between 1864 and 1868, was hailed as one of his major works (Duplessis G., 1880, p. 7), and two of his plates which he exhibited at the Salon of 1864 were awarded a medal. (Sanchez P., Seydoux X., 2005 a., Salon of 1865, p. XIV). Jacquemart was also asked by the Superintendent of Fine Arts, the Count of Nieuwerkerke (1811-1892), to illustrate part of his collection of weapons in twelve plates (1868). He was becoming distinguished as the “creator of a new genre, the rendering of art objects,” succeeding in “creating, from engravings that would ordinarily be considered merely “explanatory plates”, prints that are truly admirable, sometimes pure marvels, which themselves will one day be objects of curiosity.” (Béraldi H., 1885-1892, p. 192).

As a member of the Société des Aquafortistes, which was founded in 1862 by Auguste Delâtre (1822-1907) and Alfred Cadart (1828-1875), he engraved the frontispiece of the Society's first publication (Société des Aquafortistes, 1862, n.p.). Medalist at the Salon in 1866 and again in 1867 (3rd class medal), he was made chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur in 1869 (Sanchez P., Seydoux X., 2005 b., Salon de 1870 p. XVII), although his Legionnaire record, like that of his father, is missing. Jules Jacquemart became a member of the jury for admission and awards at the Salon for the engraving and lithography section from 1869 to 1873, then in 1880 (Sanchez P. and Seydoux X., 2005 b., Salon de 1869, p. XCVIII and CI; Sanchez P., Seydoux X., 2006 b., Salon de 1880, p. CXVIII). In 1873, he was sent to Vienna as an international member of the jury for the Universal Exhibition (Liste der Mitglieder der internationalen Jury, 1873, p. 29). As a Knight of the Order of Franz-Joseph, he became a correspondent of the Academy of Vienna in France (Enault L., 1880): his reputation was international.

His reputation even crossed the Atlantic when the Metropolitan Museum of Art entrusted him with the creation of its first portfolio in 1871, Etchings of Pictures in the Metropolitan Museum New York (London: P.&D. Colnaghi & Co., 1871), including ten etchings of paintings newly acquired in Europe by the museum, or when the American Joseph-Florimond, duc de Loubat (1831-1927), asked him to illustrate The Medallic history of the United States of America with 170 plates, 1776-1876 (New York: The author, 1878).

In 1878, Jules Jacquemart participated in the Salon after four years of absence and received a medal of honour as part of the Universal Exhibition (Sanchez P., Seydoux X., 2006 b., Salon de 1880, p. LXXXIII ). In 1879, he exhibited for the last time at the Salon by presenting Mona Lisa after Leonardo da Vinci (Sanchez P., Seydoux X., 2006 b., Salon de 1879, no 5690) and died in Paris on September 27 1880 (AP, V4E 4696). Despite the great talent of this engraver who was mainly illustrated by reproductions of objects, the change in public taste in favour of original artists' prints gradually caused the name of Jacquemart to be forgotten (Ganz J. A., 1991, p.3).

Jules Jacquemart, Watercolourist

The earliest known watercolours by Jules Jacquemart are the coloured versions of the plates from the Histoire de Porcelaine (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, inv. 21.10742 to 21.10745). It is difficult to know the function of these works, whether they were preparatory studies, or whether they were finished projects intended to convince the publisher of the talents of a young artist who was then unknown. Still, watercolour remained a medium little used by Jules Jacquemart until the last part of his life. In the early 1870s, Jacquemart occasionally used this medium for very personal works such as the Portrait en pied of his sister Marie-Thérèse, later called Mme Émile Masson (Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. RF 4194) or La chambre d’Henri Regnault après sa mort, le lendemain de Buzenval (Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. RF 5187), two works dated 1871.

During his trip to Vienna in 1873, Jules Jacquemart contracted a lung disease from which he would never fully recover. His failing health led him to spend his winters in the South of France, in Menton, until his death. These stays were an opportunity for him to produce many watercolours, to capture the landscapes and the light of "this splendid noon, [which he] love[d] so much" (INHA, Autographs 94/82490-82492; letter from M. Bailly to Jules Jacquemart of February 17, 1878). He employed a fairly limited number of tones and an abbreviated technique, which allowed him to obtain dazzling light effects, by leaving the white of the paper in reserve (Gonse L., 1881a, p. 222), as in Le Pont Carrei à Menton (?, Paris, Musée du Louvre, inv. RF 2709).

Despite a refusal of the first two watercolours presented at the Paris Salon (Dreyfous M., 1880), his works were met with great success by the public and his peers. In 1872, 1875 and 1877, he took part in the Exposition de la Société Belge des Aquarellistes in Brussels (Doc. Orsay – Boîte Jacquemart/Dépouillement des Salons Belges 1851-1900). We know that he also exhibited watercolours around 1877-1878 in Nice (INHA, Autographs 94/82490-82492; letter from M. Bailly to Jules Jacquemart dated February 17, 1878). An innovative watercolourist, he was a founding member of the Société des Aquarellistes in 1879. He was also considered a master in this field (Hôtel Drouot, 1881, p. VI). The Musée du Louvre now has a large number of watercolours made in the vicinity of Menton thanks to a bequest from Baroness Nathaniel de Rothschild (1825-1899), executed in 1899.

Jules Jacquemart and Japonisme

In his retrospective article "Japan in Paris - I", Ernest Chesneau (1833-1890) mentions Jules Jacquemart as an early Japanese enthusiast who had started collecting Japanese objects before the vogue for Japan became established among the broader public (Chesneau E., 1878, p. 386-387). It is true that Jules Jacquemart was able to become familiar with the collections of Chinese and Japanese ceramics of his father very early on and was therefore ableto get to know the collectors whose works he represented in the volume of Histoire de porcelaine that appeared in 1862.

Jules Jacquemart was well integrated in circles of Asian art lovers. He worked with Philippe Burty (1830-1890), with whom he became a great friend, then Louis Gonse (1846-1921) at the Gazette des Beaux-Arts. Around 1868, he also regularly frequented the engraver Félix Bracquemond (1833-1914), the art critics Philippe Burty and Zacharie Astruc (1833-1907), the painters Henri Fantin-Latour (1836-1904) and Alphonse Hirsch (1843- 1884), the ceramist and director of the Manufacture de Sèvres Marc-Louis Solon (1835-1913), Jules Nérat (?-?) and an unidentified person, "Prudence", with whom he formed the Société du Jinglar, a group of Republican friends who were fond of Japanese art, who met once a month, at least between August 1868 and March 1869 (Bouillon J.-P., 1978, p. 110) at Solon's in Sèvres, to have fun and drink a sour wine from the countryside called ginglard, whose name they jokingly transliterated into the mock-Japanese “Jing-lar” (Lacambre G., 1988, p. 80).

Jules Jacquemart's interest in the Far East is also evident through his artistic creations: Une exécution au Japon, also called Le supplicié Mamija Hasimé (1867), depicts a contemporary Japanese news item and was made from a photograph (Gonse L., 1876 a., p. 479). The etching Un éclat d’obus (date and location unknown) is a picturesque anecdote, which is intimately linked to the events of the Commune and presents works from his collection. Jules Jacquemart and his family were indeed in Paris at the time; he had joined the Tirailleurs de la Seine (Darcel A., 1872, p. 425). A projectile hit his home and damaged the place where his collection was supposed to be: the artist immortalised this scene where a few Chinese figurines seem to approach the rubble and look reproachfully at the intruder. Among his painted works, Jules Jacquemart produced in particular Bibelots japonais (date and location unknown), which he sent to the Exhibition of the Belgian Society of Watercolourists in 1872, under number 88 (Doc. Orsay – Boîte Jacquemart/Dépouillement des Salons Belges 1851-1900). In 1879, he made "two fans on skin decorated with Japanese objects which [he] managed to make into masterpieces of taste and originality" (Gonse L., 1881 a., p. 222) (location unknown), then, in 1880, "the delightful fan with a peach branch belonging to Mrs. Georges Petit" (location unknown). (Gonse L., 1881 a., p. 223)

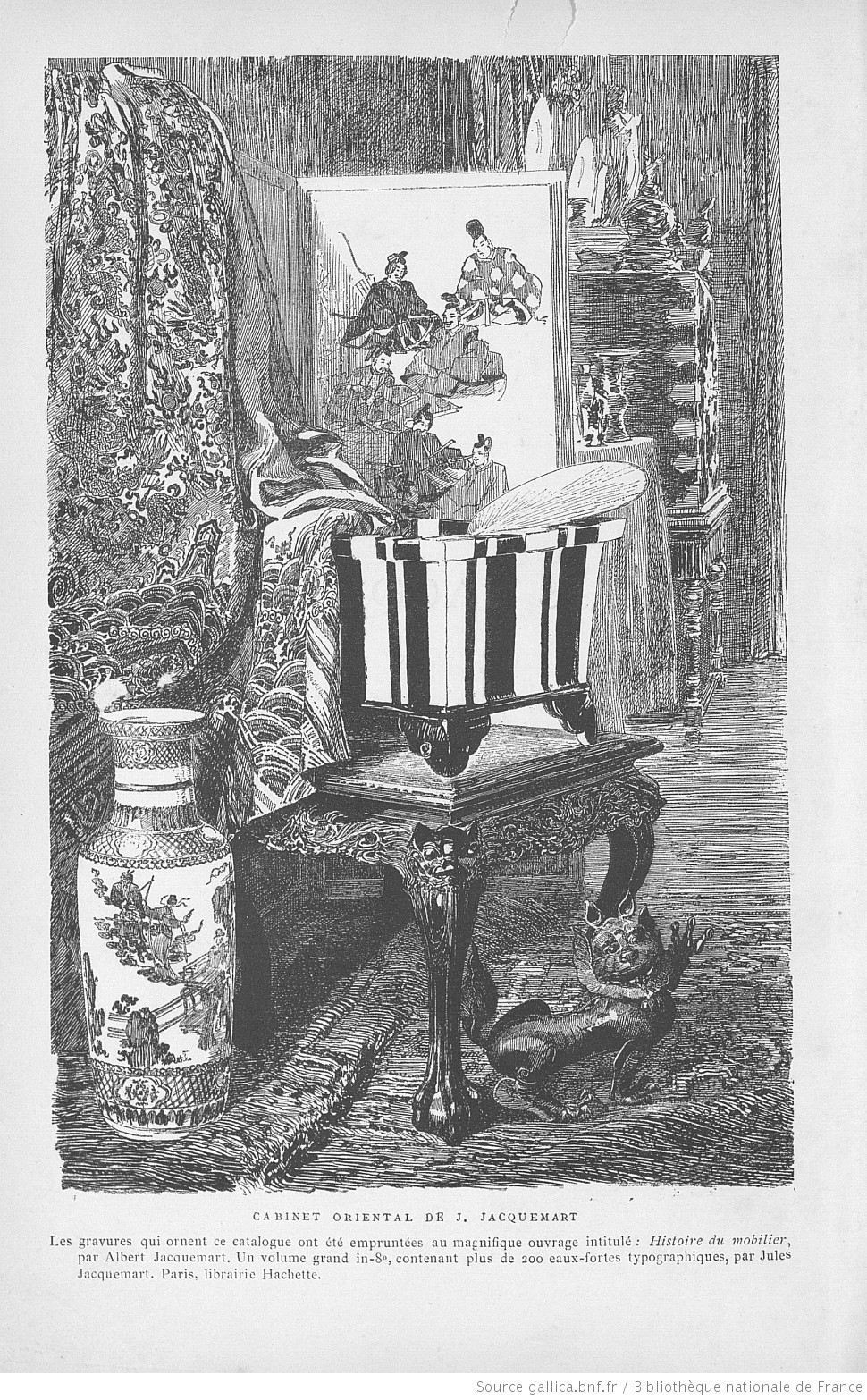

Another dimension of Jules Jacquemart's artistic Japonisme was linked to commissioned prints, which illustrated objects from Asian collections for various publications. Jacquemart thus participated very early on in the scientific dissemination of knowledge related to the countries of the Far East, not only in the press, but also at the Salon where he occasionally presented them. The vast majority of these engravings present an object in isolation, with no other staging than the slight shadow cast at their base, like the Vase chinois en émail cloisonné (1863) from the collection of the Duc de Morny (1811- 1865) that illustrates an article in the Gazette devoted to this collector (Jacquemart A., 1863, p. 411). This etching is one of those that Jules Jacquemart presented at the Paris Salon of 1863 (Sanchez P., Seydoux X., 2004., Salon de 1863, no 2655). Other prints present the works in a staged setting, like the Cabinet oriental de M. Jules Jacquemart (1875-1876?). This engraving, made for his father's Histoire du Mobilier, was captioned "Imperial robe in yellow satin embroidered with five-clawed dragons, Anam." (Cabinet oriental de M. J. Jacquemart)" (Jacquemart A., 1876, p. 219), but the composition, far from being centred on the robe, features Chinese ceramics, including a Fô dog and a part of a Japanese screen.

Jules Jacquemart also participated in the dissemination of this visual culture by lending certain works from his collection to the retrospective exhibitions of the Union Centrale des Beaux-arts appliqués à l’industrie, in particular his collection of shoes (see Commentary on the Collection, below).

According to Chesneau, Jules Jacquemart can therefore be considered an early scholar of Japan in France; however, the moniker "japonisant" should not distract from the fact that through his collection, Jacquemart was interested in a cultural space broader than Japan alone.

The Collection

Jules Jacquemart's collection encompasses three main areas: a collection of shoes from all countries and all eras; a set of "objects of art and curiosities" (especially from the Asian continent); and finally, echoing his career as an etcher, a collection of prints by artists from Western Europe. Alongside these three large ensembles, there are in particular a few works by his contemporaries, such as Femme assise (unidentified work) by his friend Giuseppe De Nittis (1846-1884) (Moscatiello M., 2008, p. 115-118) and three paintings by Antoine Vollon (1833-1900), Paysage (unidentified), another Paysage (unidentified) and Bords de rivière (c. 1860-1869, private coll.). These paintings all appeared in the posthumous sale of the artist's collection (Hôtel Drouot, 1881, p. 12).

The Shoe Collection

In the directory of collectors published by the Gazette des Beaux-Arts, Jules Jacquemart is above all described as a collector of "shoes of all periods" (Annuaire de la Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 1869, p. 279). This set was patiently put together by the artist for "more than thirty years of his life" (Du Sommerard E., 1883, p. 529); it has been demonstrated that Jules Jacquemart had been collecting shoes at least since 1863 and that he was fascinated by this research, as he mentions in a letter to his friend Armand Queyroy (1830-1893) (Gonse L., 1881 b , p. 434).

This collection consists of 310 numbers that correspond either to pairs or single shoes. It offers a great typological and cultural variety, from the "stilts of Taïtï [sic]" to the "high woman's skates" of Venetian origin from the 16th century, passing by the Egyptian sandals "of ancient origin", the "papooses from Pondicherry", "old American Indian war moccasins" and "women's shoes with small feet" brought from the Summer Palace in Beijing (Du Sommerard E., 1883, p. 553, 530, 539 , 547, 551, 550). Africa, Asia, America and Oceania are represented, although more than half of the shoes come from Europe — nearly 130 pieces. The collection of shoes from Asia still has 111 numbers: many of them are of Indian (34) and Chinese (30) origin, others are described as "Persian" (11) or "Arab" (5), and others finally come from Turkey (14), Japan (6), the Philippines (5), Singapore (2), Syria (2), Java (1), and Vietnam (1) .

Many of these shoes were featured in the 1869 Musée oriental at the Union centrale des Beaux-Arts appliqués à l’industrie (UCBAAI, 1869 c, pp. 8 and 30-31). Showcase No. 5 in Room A, dedicated to the arts of China and Japan, and Showcase No. 40 in Room E, dedicated to the "Indies", both displayed part of the shoe collection of Jules Jacquemart (UCBAAI, 1869 c, p. 8 and 30-31).

The collection was shown again at an exhibition of 1875 at the Union central that was dedicated to the history of costume. Albert Jacquemart’s article for the Gazette des Beaux-Arts about the Eastern section of this exhibition describes many pieces, and many of these shoes are also highlighted by engravings after drawings by Jules Jacquemart (Jacquemart A., 1875, p. 45-69). He is not, however, the only lender of shoes who receives mention: Eugène-Victor Collinot (1824-1889) also exhibited finds from his travels in the Near and Middle East (Persia, Ottoman Empire, etc.) with Adalbert de Beaumont (1809 -1869). But unlike the Collinot collection, Jacquemart's is centered on this type of object that is the shoe, rather than on one given region or culture. This also distinguishes it from other collections of its time: “because, at Cluny and in the private collections, unusual shoes only appear in exceptional condition and in small numbers.” (D’Hervilly E., 1880). The substantial quantity of shoes, as well as the wide variety of periods and origins represented, render Jules Jacquemart's shoe collection exceptional.

This collection was acquired in November 1880 by the Musée des Thermes et de l'Hôtel de Cluny for the sum of 10,000 F (Archives du musée de Cluny, s.c.), thanks to the involvement of Edmond du Sommerard (1817- 1885) who considered the collection "of capital interest for the history of costume in France and abroad" and for which “there was a serious interest in preventing its dispersal and preventing offers which could not fail to come from foreign museums.” (Du Sommerard E., 1883, p. XXX).

This collection is currently on deposit at the Musée international de la Chaussure in Romans-sur-Isère, with the exception of two works deposited at the Musée du château de la Malmaison and at the Musée des Arts décoratifs de Paris.

Works of Art and Curiosities

If shoes were the collector’s great passion, Oriental objects constitute a second centre of interest for Jules Jacquemart. The part of the "objects of art and curiosities" of the sale catalog (Hôtel Drouot, 1881, p. 13; Lugt no. 1395) brings together 311 lots, to which were added 16 lots corresponding to European objects. We thus find a majority of oriental weapons (63), ceramics (48), bronzes and coppers (47), a few pieces carved in wood (15), goldsmiths or precious materials (14), works in lacquer (9), cloisonné and painted enamels (6), and furniture from the Orient (13). There is a large number of textile, cloth (37) and carpet (5) works, as well as numerous miniatures, paintings, scrolls or albums from various Asian countries (54). The geographical origin is regularly indicated (for 237 numbers out of the 311 non-European considered), a feature that makes it possible to note the great variety of the origins of the objects: 76 numbers are associated with India and Kashmir, 57 with the Near and Middle East (corresponding to "Oriental", "Arab", "Persian", "Asia Minor" and Syrian objects) to which are added some objects from the Maghreb (Morocco, Tunis, and Kabyle), 43 lots for Japan, 31 for China and Mongolia and 29 for the countries and regions of Southeast Asia (Tonkin, Siam, Malaysia, Annam, Java, Cochinchina).

Jules Jacquemart lent some of these objects to the Musée oriental in 1869 (Archives du musée d’Arts Décoratifs). Some are mentioned in the visitor's guide that accompanied this exhibition, which thereby testifies to their quality, their rarity, or their remarkable picturesque aspect. In addition to the showcases of shoes, the loans from the room of the Indies are particularly underscored, with the theatre accessories (two masks from Siam, an Indian puppet), Indian and Persian miniatures, a teapot in painted enamel with two porcelain cups, and, among the various weapons, a "rhinoceros-skin rondache" (UCBAAI, 1869 c, p. 30-32).

Jules Jacquemart's collection of oriental objects was dispersed after his death. The extremely luxurious sales catalog pays a final tribute both to the talent of the artist and to the beauty of the works, through numerous illustrations engraved by Jacquemart or from his drawings, found in Histoire du mobilier or other publications.

The sale took place from April 4 to 8, 1881 at the Hôtel Drouot and attracted buyers, including Siegfried Bing (1838-1905) and Philippe Sichel (1840-1899) (AP, D48E3 69). The highest price paid was 1710 F, for a "cabinet in old Japanese lacquer with a black background and gold decoration, with copper trim, engraved and gilded [which] rests on its cut-out wooden table" (lot no. 308). The weapons category, quite popular among collectors, saw great success with the sale of a Persian sabre (lot no. 174), an Indian spearhead (lot no. 159) and an Indian spear (lot no 160, illustrated) to a certain M. Grandmonge for 700, 600 and 650 F. That of Indian and Persian miniatures, less common, was also popular; a "volume containing thirty-four very fine Indian miniatures with binding of the time in red, embossed and gilded morocco" (lot no. 363) was acquired by Georges Petit (1856-1920) for the sum of 800 F, and the specialist Alfred de Lostalot (1837-1909) was able to acquire many miniatures.

The Collection of Prints

Jacquemart's collection of prints and albums includes 206 numbers in the catalog for the 1881 sale. It primarily includes works of his contemporaries or near contemporaries, mainly etchings or lithographs but also examples of older artists, dating back to the Renaissance.

Having apparently had no master in engraving, Jacquemart had to find a repertoire of forms and graphic solutions through these plates and his own reflection. He was thus able to carefully observe proofs of old etchings by Jacques Callot (1592-1635) and Giovanni Battista Piranèse (1720-1778) as objects of study.

This set was also the subject of enjoyment: the presence of rare proofs, complete series, prints at various stages (many prior to the final version), or prints on Chinese and Japanese paper, or even on vellum, testify to the particular care that Jacquemart put into composing his collection. He thus possessed a test proof of Kensington-Gardens, petite planche (lot no. 712) by Francis Seymour-Haden (1818-1910), as well as its counter-proof; he also has eleven etchings by James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) on which is indicated "very rare proofs, first printing, several on Chinese paper" (lot no. 734).

The high proportion of works by contemporary engravers and lithographers invites us to speculate upon the social dimension of this collection. Jacquemart knew, or had managed to befriend, certain artists whose works he collected. He thus had a certain number of works by colleagues from the Société des Aquarellistes, such as Bracquemond (48 works), Jules Michelin (1817-1870) (42), Léon Gaucherel (1816-1886) (30), Charles François Daubigny (1817-1878) (22), and Alphonse Legros (1837-1911) (15). Other works were by his friends Armand Queyroy (9 works) and Hector Giacomelli (1822-1904) (3). He also owned works by Belgian etchers, such as Félicien Rops (1833-1898) (17 works), who came to Paris to study etching with him (Lemonnier C., 1908, p. 83). Several proofs are signed. Thus, these prints collected by Jacquemart also testify to social ties and types of mutual recognition among artists.

Related articles

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne