The financial and monetary aspect of the spoliation of artworks during the Occupation

One of the lesser known aspects of the looting of artworks during the Occupation concerns goods “freely” exchanged on the art market.1 Although the question of objects transferred unilaterally, confiscated or taken by force, has been relatively well researched,2 the same is hardly true for purchases at market prices from private consenting sellers. During this period, the art market in France, as in other occupied countries, was extremely lively, involving numerous actors, both German and French.3 In theory, the price of a work of art that results from the free play of the market reflects the free and non-constrained agreement between parties.4 There would thus be no criticism of the sale of a work of art by a French person to a German. However, as André Istel observed in 1944, this appearance of contractual normality is deceptive and such acquisitions should be considered looting:

“The scientific looting method developed by Germany […] consisted in having the Banque de France credit the Occupation authorities, for the so-called benefit of the troops, an amount of francs way above the needs of the latter. These francs served the purpose of undertaking a huge roundup of all goods available: food, machines, shares, objets d’art, buildings, etc. Even consciences did not escape it; nor was the daily roundup of 500 million francs enough. Franco-German compensation agreements were manipulated in such a way as to create a deficit in Germany’s favor of thirty-odd billion francs in 1942 and 50 in 1943. The sums of money paid to Germany in 1943 were four times the total budgetary revenue of France before the war; taxes during the Occupation, while increased, hardly covered a third of State expenses; monetary circulation, which was approximately one hundred billion francs before the war, is today six hundred billion; Public debt, which was approximately 400 billion before the war, is now 1,500 billion.”5

If money has always driven the war for the art market, this was all the more true during the Occupation. In fact, a limited number of works were exchanged for a virtually unlimited amount of money.

In order to understand the commerce of looted artistic works, it is necessary to analyze the mechanisms by which the Occupation was financed. Three instruments can be identified for that purpose: the Reichskreditkassenscheine (RKKS), the Franco-German clearing house of the Deutsche Verrechnungkasse (DVK), and the costs of the Occupation.

The RKKS system

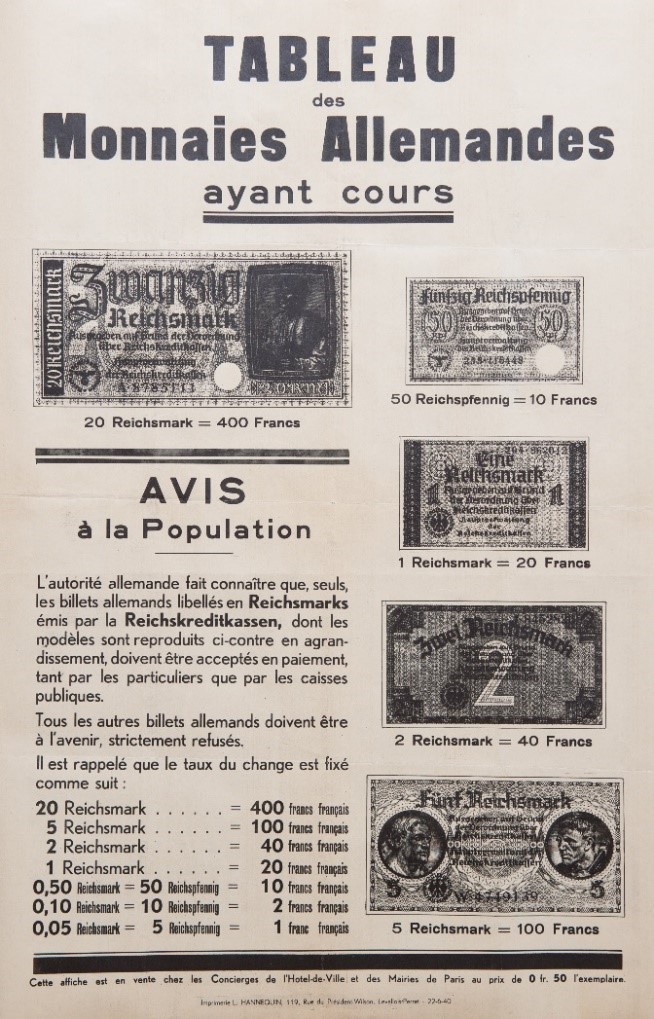

The Reichskreditkassenscheine (RKKS or scrips) were special bills printed in Germany and labeled in marks. They were used by the German troops for their expenses in the enemy zone. They had a single rate of exchange and were used to pay expenses in conquered territories.

These bills were “progress” compared to orders of requisition in kind. From an economic point of view, the occupied party who accepted a bill in exchange for goods or services theoretically possessed credit with the occupier. The creation of RKKS is in conformity with the law of war and the 1907 Hague Convention signed by all the European countries including Germany.1 The Convention stipulates that looting is a war crime2 and that private property cannot be confiscated (article 46). However, it specifies that “if […] the occupant takes contributions in money in the occupied territory, this can only be for the needs of the army or the administration of the territory” (article 49): “Requisitions in kind and services can be demanded only […] for the needs of the occupation army. They will be related to the country’s resources […]. Benefits in kind will be paid for in cash, when possible; if not they will be stated in receipts, and payment of the sum owed will be made as soon as possible” (article 52). The principle of the RKKS is therefore not at fault, since the Allies used occupation currencies of that type in 1944 and 1945. Looting only resulted from the abuse of them.

Originally, the RKKS in Germany were meant to replace coins in strategic metals (silver and nickel) when the country went to war. They had only been printed for small amounts, from 50 Reichspfennigs to 5 Reichsmarks.3 It was finally decided not to put them in circulation but to increase the use of Rentenbank bills of a low denomination,4 to issue a new 5 mark Reichsbank bill5 and to strike coins in zinc and aluminum. Because of their rapid military success in Poland, the German authorities decided that in occupied territories they would use not the Reichsbank bills used in the Reich, but the RKKS. For this reason, the issuing authority, the Reichskreditkasse (RKK), was created in Berlin6 on 23 September 1939 under the control of the Reichsbank.7

The RKK made it possible confine the use of Reichsbank marks to German territory, avoiding the import of inflation suffered inevitably by the occupied countries, and to provide resources to the Reich. As explained by Emil Puhl, president of the RKK and vice-president of the Reichsbank: “by transferring the financing of German needs to occupied territory, the RKK economize the corresponding funds for the Reichsmark account and benefit German money. These discreet banking means and techniques with which these moneys insinuate themselves into a country and integrate it into our war economy have in the past proved their great efficiency.”8 A considerable advantage, RKKS were in addition an efficient means of pressure on occupied countries: “The issuing of RKK-Scheine ensure that when we enter foreign territory we are able to immediately cover the financial needs of German troops in the occupied territory itself. In addition, the RKK immediately take care of the temporary financing of clearing operations between the Reich and the occupied country. From the monetary point of view, that allows us to force the national issuing bank into submission until, by means of its own money and advances on clearing operations, it gives in and puts the necessary money at the disposal of German troops. If the issuing bank refuses or if it cannot be returned to working order, we found a new issuing bank that takes over.”9

The German ordinance (Verordnung) of 3 May 194010 specified (article 1) that “to supply German troops and German administrative authorities in Denmark, Norway, Belgium, France Luxemburg and the Netherlands with means for payments and to maintain transactions and economic life in these territories, Reichskreditkassen bills and moneys will be issued.” The text was revised by a decision of the army commander on 18 May 1940, which stipulated in addition that “the ordinance is in force from the moment of occupation.” A note (Bekanntmachung) of 19 May 1940 by the commander in chief of the army, indicated that “in the occupied territories of Belgium, France, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, Reichskreditkassen bills will be issued in the same manner [as in Denmark and Norway].” Additionally, the use of Reichsbank and Rentenbank bills was formally prohibited in France. The exchange rate was overvalued at one mark for 20 French francs.11 This rate, very favorable for Germany, enabled it to supply itself cheaply in the occupied zones. The population was informed by the press and by posters. (see Fig. 1)

To avoid bypassing the exchange rate, the decree of 20 June 194012 blocked all prices, threatening offenders with prison sentences and high fines.13 The RKK had a quasi-unlimited issuing power, in the sense that their counterparts were virtual.14 The economist René Sédillot observed that RKKS were “paper [that] covered paper,”15 adding that “in reality a money like that one was only backed by the Wehrmacht’s machine guns.”16

The reimbursement of these bills between 1940-1944, charged to the costs of occupation, (see below) amounted to something like 50 billion francs.17

Source : Collection of the Banque de France.

The DVK Clearing house

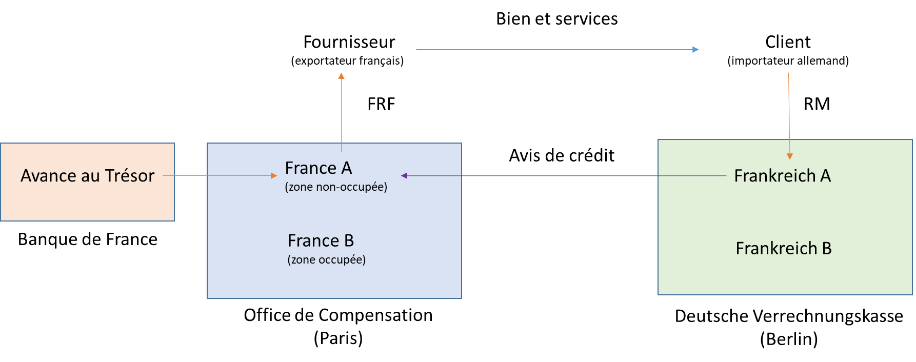

A new clearing system was put in place for distance payments between France and Germany – that is, for compensation. This type of agreement allows two countries to trade without exchanging currency or having recourse to barter. It is useful if there is a shortage of currency or inconvertibility of moneys. Commercial operations are subject to the authorization of the compensation entity. Each entity receives the payments that are to be made in favor of the other country and notes them in an account. If the trade balance is in equilibrium, the two accounts in each of the entities are equal and can begin again at zero. Each compensation office uses the money received from its importers to pay its exporters. The difficulty lies in cases of disequilibrium: the country whose exports exceed its imports, in which case it can either grant the other country credit, or cease any new exports.

In trade agreements before the war, France was in a better position regarding Germany, which was leading an autarchic policy.1 The 1940 defeat reversed the balance of power and in the new agreement of 14 November 1940, France was obliged to finance a surplus in the trade balance, contrary to Germany, which was not. Since German exports were caped and subject to administrative authorizations, the French authorities were quasi unable to use their France A and B accounts (corresponding to occupied and non-occupied zones) mark balances to obtain German goods and services, with the exception of raw materials, which would be transformed (by the French) into finished products to be used by the Reich.

In December 1940, it was decided that payments between France and Belgium would be made through the DVK in Berlin.2 Other countries were also bound by clearing agreements passing through Berlin – Belgium (11 January 1941), the Netherlands (17 February 1941), Norway (9 October 1941) and the Anglo-Normand Islands (15 January 1943). Accounts for Luxemburg and Alsace-Lorraine were also opened in the DVK books.3

This mechanism led to the unlimited financing of German imports by the French Treasury. In addition, numerous abuses and frauds were committed concerning the nature of the goods traded, notably on the art market.4

Occupation expenses

The expenses involved in the Occupation were the main tool of spoliation. They were conceived as a useful expedient while awaiting the peace treaty, which seemed imminent – in fact the armistice signed on 22 June 1940 provided (article 18) that “the expenses of German occupation troops will be borne by the French Government”. A little more than two months later, Hans Richard Hemmen, who was in charge of the economic and financial aspects of the armistice in the Wiesbaden Armistice Committee (Waffenstillstandskommission or WAKO), specified the terms (note of 8 August 1940):1

- According to article 18 of the Franco-German Armistice Convention of 22 June 1940, the maintenance costs of the German occupation troops on French territory are the responsibility of the French Government. […]

- Considering the impossibility of evaluating the exact amount of these costs at the present time, until otherwise specified, it is necessary to pay in installments of 20 million RM per day. [ …] The conversion into French francs will be made in the basis of 1 to 20, unless a different rate is later set. […]

- Payment by installments will begin on 25 June 1940. Payments must be made each time in advance for ten days. […] Payments must be made to an account named “occupation expenses” at the Banque de France, in Paris, at the free disposal of the Head of the Military Administration in France.

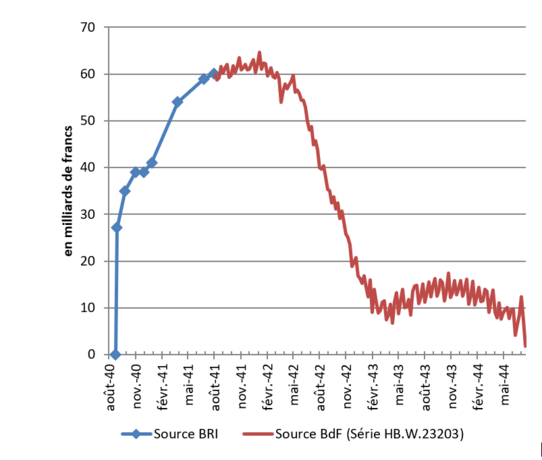

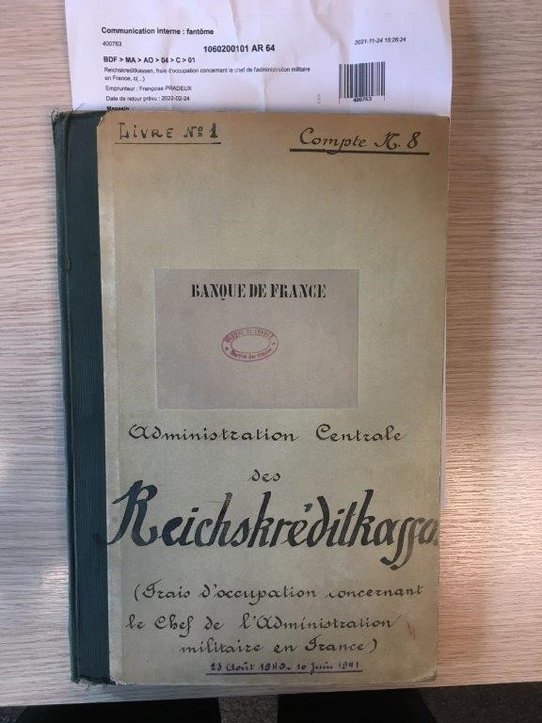

The exorbitant choice of 20 million marks per day, or 400 million francs, had no relation to the maintenance costs of occupation troops. The figure was meant as a reminder of the amount of reparations provided for in the Versailles Treaty (20 billion gold marks). To pay these costs, the Vichy government called on the Bank of France, which opened an account to the RKK in its books. The balance on the account literally exploded (cf. Graph 1 and Figure 2), its resources greatly exceeding its expenses – at least until the construction of the Atlantic wall. The manna was distributed among the various German services by the Militärbefelshaber in Frankreich (MBF), whose economic affairs section (Abteilung Wirtschaft) was directed by Elmar Michel.

There seem to be no specific studies of the functioning and internal mechanism of this scheme. However, it is possible to infer that the decisions regarding its use depended both on the sums engaged and the German authorities, which had limited budgets. Berlin only intervened in cases of larger sums. To this day, it is not possible to know, when Carl Schaeffer, commissioner at the Bank of France (Deutsche Kommissar bei der Bank von Frankreich), decided to buy artworks for the Reichsbank,2 whether he bought them on his own operating budget or whether he had to solicit funds and a specific payment authorization from Paris or Berlin.

Source : Demand obligations – Current credit accounts – Central administration of the Reichskreditkassen in

Patrice Baubeau, The Bank of France's balance sheets database, 1840–1998: An introduction to 158 years of central banking, Financial History Review, 2018 25(2), 203-230. doi:10.1017/S0968565018000070 (supplemental material) for the BdF source and Annual Report of the Banque des Règlements Internationaux (International Payments Bank (years 1940 et 1941).

Source : Paris, Archives of the Banque de France, boxes 1060200101/64 and 1060200001/460 on the follow-up of payments and expenses on current account n°8 (Occupation costs concerning the Chief of the Military Administration in France).

Artistic Spoliation

With the extension of the war, the main objective of the Reich was to exploit conquered economies without causing their fall (Kriegswirtschaftliches Optimum). Money was the basis of this aim, as stated by Knapp in his Staatliche Theorie des Geldes.

The combination of RKKS, clearinghouse, and overvalued occupation costs enabled large scale spoliation. Disposing of unlimited free resources, the occupier could buy at market price (or under) artworks from sellers in need who lacked other resources. The system turned out to be all the more perverse and inexorable, as it set in motion a spiral of inflation that lowered the real value of most other financial assets (pensions, bonds, etc.), forcing those who possessed real liquid assets (gold, precious stones, furniture, paintings, etc.) to part with them in order to pay for basic needs. A second advantage of this arrangement was its creation of a unified monetary space that functioned for the benefit of the occupier.1 The recycling of liquid assets allowed for the laundering on the scale of “Greater Europe” (see fig. 2) of both artworks and gold: “Certain army paymasters […] fraudulently introduced coupons they had bought for Reichmarks in Russia from soldiers on leave, for a less than the official rate.2 The French bills they got in exchange for these RKKS were then used to buy gold in France3 or were introduced fraudulently into Switzerland, via Berlin, to be exchanged for Swiss francs.4 The best informed observers of the time5 had noted the “peaking” of gold-moneys following the introduction in France of RKKS issued in the Balkan countries or exchanged for French bills. “The francs thus obtained were used for the purchase of objects in gold which would then follow the path of oriental countries, Greece in particular, where gold pieces were among the most sought after.”6

The history of the financial and monetary aspect of artistic spoliation in France remains to this day relatively little known.