DARD Marie-Henriette and PICHOT L'AMABILAIS Henri (EN)

A Discreet Art Lover from Dijon

Henri Pichot L'Amabilais (1820-1869) was born in Dunkirk on October 12, 1820 (AD 59, 5 Mi 027 R 032) and was the son of Pierre Jean-Baptiste Pichot L'Amabilais (1791-1847), a polytechnician and captain in Army Corps of the Duc d’Angoulême (AN, LH//2148/69), and Thérèse Virginie Justine Deschodt (1796-?), daughter of a sub-prefect from the North (Guillaume, M., 1981-1982). Henri Pichot L'Amabilais inherited the title of baron from his maternal grandfather in 1838. The young man enrolled at the Faculty of Law in Poitiers, then in Dijon. Meanwhile, his father received his appointment as Chief of Engineering at Auxonne in 1841. In 1845, Henri Pichot L'Amabilais obtained a doctorate. Although he interned as a lawyer from 1846 to 1849, he seems to have never argued a case and was thereafter referred only by his function as "landlord", collecting several estates which ensured him a comfortable existence (Guillaume, M., 1981- 1982 and Jugie, S., 2000). In 1851, Henri Pichot acquired a hôtel particulier at 9 rue Saint-Pierre in Dijon, present-day rue Pasteur (Guillaume, M., 1981-1982). There he was joined in 1868 by Lucie Liautaud (1825-1868), the mother of their daughter, Marie Henriette, born in Dijon on November 13, 1845 (AD 21, FRADO21EC 239/306), although only for only a few months, as she passed away later that year (November 15, 1868).

The baron himself died on March 8, 1869 in Dijon, at the age of 49 (AD 21, FRADO21EC 239/360), bequeathing his fortune and his collection to their daughter, whom he never acknowledged (AD 21, 3 Q 9/290). The same year, Marie-Henriette Liautaud married Doctor Paul Dard (AD 21, FRAD021EC 239/359). The couple moved into their father's hôtel particulier and cared with great discretion for the rich collection that the baron had built over nearly two decades: "during their lifetimes, out of dislike for intruders, and especially merchants and antique dealers, they kept the doors of their home strictly closed" (Chabeuf, H., 1916). Marie-Henriette Dard (1845-1916) died on February 27, 1916 (Archives of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Aa 17, copy of death certificate). Childless, she bequeathed all of her artistic collections to the city of Dijon in a handwritten will of January 30, 1911 (AM Dijon, 4R1/147), on the condition that they be displayed within the museum in a section bearing the name of "Salle du Docteur et de Mme Paul Dard" (deposited in the minutes at the office of Maître Paul Darantière, notary in Dijon, on February 28, 1916, see extract AM Dijon 4R1/147).

Beyond these slim biographical facts, the personality and social networks of Henri Pichot L'Amabilais remain mysterious, to say the least: while the museum commission paid tribute to "an excellent connoisseur" (Archives of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, C3, session of May 12, 1916) when acquiring his large collection in 1916, the amateur did not appear among the members of the Académie de Dijon or the Commission des Antiquités de la Côte-d’Or (Jugie, S., 2000). Only the few memorabilia brought back by Henri Chabeuf (1836-1925), a historian and eminent figure in regional learned societies, enable the collector to be linked to scholarly circles in Dijon. The man who "formerly visited the Pichot museum and [was] really dazzled by it" took up his pen at the time of the 1916 bequest, sketching a posthumous portrait of the baron and at the same time delivering some clues regarding the collection’s provenance: "For a long time Baron Pichot took for himself the finest pieces that flowed from all sides into the Tagini stores, and, like cousin Pons de Balzac, everything was good for him, as long as the pieces were beautiful and intact" (Chabeuf, H., 1916). Frédéric Tagini (? - 1877), an antique dealer of Italian origin, installed prominently in the former Palais des États de Bourgogne, on rue Condé (current rue de la Liberté), was thus most likely the main supplier of Pichot L'Amabilais. We do not know whether he also traveled to Paris or abroad to enrich his collection in Dijon.

The Eclectic Cabinet of Pichot l’Amabilais

In 1916, the bequest of Doctor Dard's widow provided to the Dijon museum a "collection assembled by a man of taste who did not specialise in any branch of beauty" (Chabeuf, H., 1916). The whole - which numbers 1,377 entries in an initial museum inventory (Archives of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Aa 8), out of the 2,088 numbers of the posthumous inventory of 1916 (Archives of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, Aa 9), and which may have been subject to other cuts approved by the Museum Commissions of 1917 and 1932 (AM Dijon, 4R1/147 and Archives du musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, C3) - shows an extraordinary diversity of techniques, periods, and (to a lesser extent) geographical origins. In its eclecticism, it admirably reflects the sensitivity of Baron Pichot L'Amabilais to all manifestations of art: paintings (over 170 numbers, including around 30 works by Swiss and German primitives), drawings, illuminations, miniatures, sculptures (around 70 works), ivories, pewter, bronzes, furniture (75 entries), ceramics (over 500 pieces), jewellery, goldsmithery and silverware (240 objects), enamels, various objets d'art, stained glass, glassware, and arms (115 pieces). Arms (from the Islamic world, Africa, and Oceania) as well as "various objects" (jades, cloisonné enamels, bronzes, lacquers) and especially ceramics (Iran, China, Japan, East India Company) testify to the curiosity for the faraway that contributed to the richness of this mid-19th century cabinet. In the extra-European collection, equivalent to nearly a quarter of the collection listed in the inventory (about 330 objects), Asia is represented by a significant set of 215 porcelains from China (in particular emblazoned dishes, blue and white and famille rose decorations) and Japan (mainly Imari decorations, vases and mounted cups).

The Witness of a Curiosities Market in Dijon

The thousand objects entered by the Dard bequest has the advantage of offering a remarkable overview of "the quality and variety of finds that an enlightened amateur could make on the art market of a provincial town in the middle of the 19th century” (Jugie, S., 2000, p. 281). Indeed, the scholar and chronicler of regional artistic life Henri Chabeuf explicitly associates the origin of the collection of Pichot L'Amabilais and the Dijon store of the antique dealer Frédéric Tagini (? - 1877), who was soon assisted by his eldest son Edme (1827-1903). Initially installed at no. 4 rue Chaudronnerie, this highly visible trade in curiosities and works of art then enjoyed a prime location within the Palais des États de Bourgogne, from 1852 in its western wing, along the rue Condé (now rue de la Liberté): "It was in its heyday that the Pichot collection was formed, in 1848, especially, and also in the following years" (Chabeuf, H., 1916). And it was no doubt to house and display his collection that the baron left his residence on rue Berbisey for a hotel acquired at no. 9 rue Saint-Pierre during these same years (in 1851). The testimony of Chabeuf, who frequented the Tagini shop and could be informed directly by the merchant, or by one of his sons, is further supported by the discovery on one of the paintings in the collection, a Saint Jérôme (inv. DA 105 A) of the Swiss school of the 16th century, an inscription on the back of the panel: “6 panels of old paintings [sic] for Mr Tagini Md d'Antiquités à Dijon.” (Jugie, S., 2000, p. 279). However, Chabeuf's indications and this material evidence cannot completely rule out the possibility that the collector, who neither catalogued his acquisitions nor left any account books, also supplied himself through trips to Paris or abroad, notably in Switzerland where the Retable de Pierre Rup (inv. DA 97) was in 1853 still in the hands of a certain Kuhn, art dealer in Geneva (Guillaume, M., 1981-1982, p. 177).

The Dard Bequest Enters the Museum

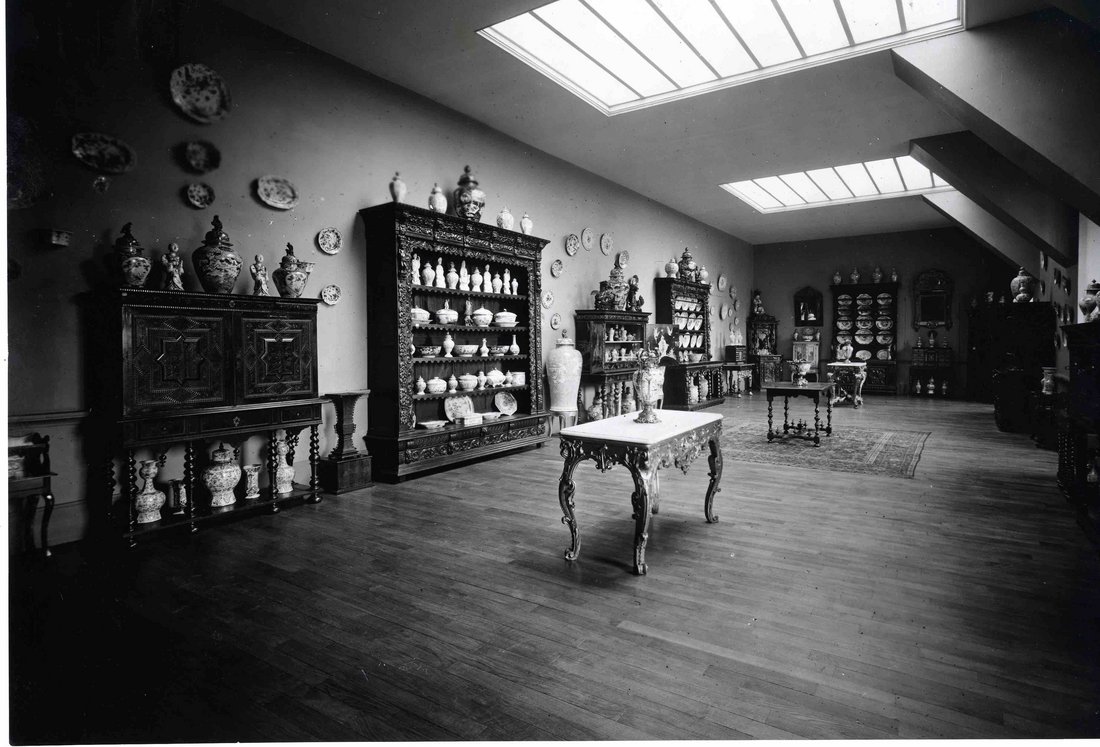

While the municipal council of the city of Dijon quickly accepted the legacy of Marie-Henriette Dard in its deliberation of March 20, 1916 (AM Dijon, 4R1/147), the presentation of the collection was delayed by disputes from heirs and the context of World War I. In March 1917, all the paintings, arms, and some sculptures were deposited in the museum as a measure of safeguard, but it was not until 1921 that the bequest was finally handed over in its entirety (AM Dijon, 4R1/147). In the meantime, the expert Paul Deveaux had been entrusted in 1917 with the selection of the objects submitted to the Museum Commission (AM Dijon, 4R1/147). The collection was then quickly, but very briefly, opened to Dijon notables on June 28, 1921, in the rooms on the ground floor of the 18th century wing of the museum (Archives of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, C3, session of May 12, 1921). It was still ten long years before the collection found its final disposition in 1931 in the course of the museum, the time to carry out the campaign of restorations required by the poor condition of the works (Archives of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, C4, session of May 22, 1930) and to resolve, for lack of space, to install it in seven specific but nevertheless dispersed rooms, thus going against the donor’s wish to have a single collection inaugurated in memory of the Dard couple. The primitives (Konrad Witz, Master of the Passion of Darmstadt, Master of the Carnation of Baden, among others), who made the Dard legacy famous from the end of the 1920s (Réau, L., 1929), were placed in first floor of the museum, in the room at the corner of rue Longepierre and place de la Sainte-Chapelle; the objects of religious art (until 1935 and a transfer to the Chapelle des Élus du Palais) and arms on the second floor, on the place de la Sainte-Chapelle; furniture and ceramics on the third floor of the 18th century wing (Jugie, S. 2000). In this latter section, a confidently eclectic mélange, were German and Nordic cabinets, French or Saxon porcelain, archaizing Chinese bronzes and a pair of large "blue and white" vases from China, Japanese mounted ceramics with Imari decoration on Rococo consoles in gilded wood, not far from a carved and engraved ivory cabinet (inv. DA 311), characteristic of the production of Vizagapatam (Archives of the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Dijon, old photographs of the rooms).

The outbreak of the Second World War, followed by a completely redesigned museum itinerary, kept a large part of the extra-European collection of the Dard legacy in reserve from the 1940s: the vast display of Dard ceramics, hung on the wall and arranged on sideboards and "stylish furniture" in a sought-after effect of strong accumulation, had thus given way to the refined museography of "modern display cases" obeying the typology of centres of creation and families of decorations. It was not until 1970 and the opening of the "Salle de l'Asie" at the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Dijon (thanks to a deposit of works from the Jacques Bacot collection of the Musée Guimet obtained by the curator Pierre Quarré ) that some Far Eastern pieces from the Pichot L'Amabilais collection became once again visible to the public.

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne

Collection / collection d'une personne