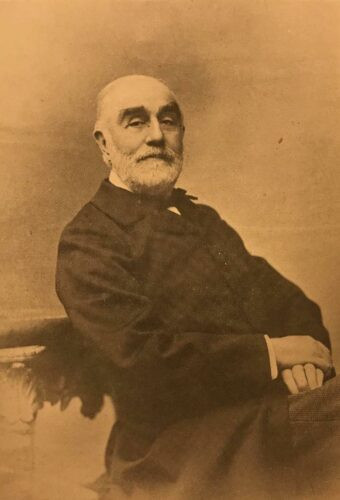

GRANDIDIER Ernest (EN)

Born in Paris on 2 December 1833, it was here that Ernest Grandidier grew up, studied, and spent most of his life. Living with his father, François-Napoléon Grandidier (1802–1870), his mother-in-law, Zoé Cardon, and his younger brother, Alfred (1836–1921), the young Ernest was brought up in the Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré. His mother, Marie-Ange Delalevée (1813–1838), died when the two brothers were still children. Ernest Grandidier came from a wealthy family: her father was a notary and had many annuities and properties. The children benefitted from a good education and frequented the capital’s haute bourgeoisie, particularly through the intermediary of the Cardon family. The years spent in Paris were interrupted by travels on the Mediterranean coast and in Italy. The absence of Ernest Grandidier’s memoirs or private correspondence make it difficult to gain a better understanding of his youth. All the same, the study recently undertaken by Jehanne-Emmanuelle Monnier (2017) about Alfred Grandidier’s life and geographical ventures gives some indications about his life. Very close to one another, Ernest and Alfred attended the same lessons, whether instructed by their father, or a tutor, before Ernest decided to study law and Alfred the natural sciences.

Youthful travels: two years spent in the Americas

In 1856, at the age of twenty-three, Ernest Grandidier finished his legal studies. He wanted to become an auditor in the Conseil d’État, but no admission competition was scheduled. He decided instead to accompany his brother and his tutor, Jules Janssen (1824–1907), on a trip to the Americas, which was quite common amongst wealthy young individuals at the time. Ernest set out to assemble ‘collections of natural history and, above all, mineralogy’ (MNHN, MS. 2807), whilst Janssen and his young pupil focused mainly on physics and astronomy (Monnier, J.-E., 2017, p. 51). The Grandidier brothers embarked in October 1857 (Grandidier, E., 1861, p. 4), and travelled to the United States from Liverpool. When they returned in 1859, their journey had lasted just over two years.

Their trip commenced in North America. They were helped by the many letters of recommendation they had been given, and the first part of their sojourn primarily consisted of a series of social calls and visits. At the beginning of 1858, they travelled to the southern part of the continent and joined up with Janssen who had come from France (Monnier, J.-E., 2017, p. 54). Before leaving, the two brothers were entrusted by the French Minister of Public Instruction with a ‘free scientific mission’ to assess ‘certain of the planet’s physical aspects’ (Grandidier, E., 1861, p. 269) in association with the studies undertaken by Janssen. But illness prevented the latter from staying more than several months in South America and he eventually returned to France with the astronomical equipment required for his experiments (Monnier, J.-E., 2017, p. 55). Hence, a new phase in the trip began, during which Ernest and Alfred crossed the Andes several times in search of unexplored lands. From Amazonia, they went to Peru (in particular the cities of Cuzco and Puno), Bolivia, Argentina (Buenos Aires), and Brazil. They returned to Le Havre in November 1859. In addition to the experience gained during this first trip, the two young men brought back several species of reptile, grains, and geological and mineralogical samples. And they donated ethnographic objects to the Musée des Antiquités Impériales in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, the Invalides, the Louvre, and the Trocadéro (Monnier, J.-E., 2017, p. 63). The Grandidier brothers’ trip was well received by Parisian scientific circles, which praised the quality of the information brought back and the courage of the two young men. Following their adventures, Ernest wrote Voyage en Amérique du Sud. Pérou et Bolivie, which was published in 1861, and it was in his role as ‘the author of scientific studies about America’ that he was made Chevalier de le Légion d’Honneur the following year. This first trip was highly instructive and was decisive for Alfred’s subsequent career, as he continued with explorations in India, then stayed in Madagascar, where he mapped out the island. He subsequently became a respected member of the Société de Géographie.

His life in Paris, where he compiled his collection

When he returned to France at the age of twenty-five, Ernest Grandidier became an auditor in the Conseil d’État. His career, about which little is known, came to an end just before the fall of the Empire in 1870 (Annuaire-almanach, 1870, p. 316). The exact date he began his collection is to this day unknown, but his collections did grow in the 1870s. He seemed to be primarily interested in books (Kœchlin, R., 1914, p. 9) and objets d’art. He devoted himself to collecting Chinese porcelain, which gradually became the preferred specialisation for his collection. He assiduously frequented the Parisian market, and in particular the Parisian dealers Siegfried Bing (1838–1905), Philippe Sichel (1841–1899), Laurent Héliot (1848–1909), and Florine Langweil (1861–1958) (Chopard, L., 2020). He was also in contact with other collectors, such as Henri Cernuschi (1821–1896).

Alfred Grandidier wrote in his Mémoires that Ernest’s love of Chinese porcelain came from Eugène de Vandeul, the nephew of his mother-in-law, whom both brothers were close to: ‘he was a great art lover and had beautiful furniture, including a charming “tronchin” (a writing table), which Albert left to me in his will, pictures, and, above all, Chinese porcelain pieces that inspired my brother with a taste for them’ (MNHN, MS. 2807). A widower and childless, Ernest Grandidier had a large fortune at his disposal, enriched by his inheritance from his father and his properties. He inherited, in particular, from his father’s estate, the Château de Fleury-Mérogis. This was the famous ‘property near Corbeil (…) “converted” into porcelain’, which Raymond Kœchlin referred to in 1914 (Kœchlin, R., 1914, p. 10). Nothing formally indicates that the collector sold it with the intention of buying new porcelain objects; however, Alfred Grandidier did mention the same anecdote in his Mémoires (MNHN, MS. 2807).

Ernest Grandidier made many donations to the French State in his lifetime (Les Donateurs du Louvre, 1989, p. 222), but the most important of these was the donation of his collection of Chinese porcelains to the Musée du Louvre in 1894. He did set out a number of conditions, which specified that he would be the sole curator of the collection until the end of his life, that every year a sum of money was to by granted by the museum for it growth, and that an ensemble of rooms should be created to house his porcelain objects. This was the first collection consisting solely of Chinese porcelain wares to be integrated into the museum. Although it was naturally incorporated into the Department d’Objets d’Art du Moyen Âge, de la Renaissance et des Temps Modernes, Grandidier was relatively autonomous compared with the other curators.

Inaugurated in June 1895, the rooms that housed his collection were located on the mezzanine floor adjoining the Grande Galerie (Joanne, P., 1912, p. 9). The porcelain items were arranged in large showcases and this presentation is attested by two photographs dating from 1909 (Geffroy, G., 1909, Plates inserted after pp. 102 and 104). In a second donation made in 1895, Ernest Grandidier’s second collection was added to that of the Louvre: this was a donation of Japanese ceramic wares. These two donations were very significant, both in terms of the number of donated objects and their financial value. Right up until the end of his life, Ernest Grandidier constantly watched over his collection and continued to enrich it with donations and acquisitions. He died on 14 July 1912 in his home, at 8 Bis Avenue Percier in Paris, at the age of seventy-eight. After his death, his collection continued to form a unique and important entity in the Louvre’s Far-Eastern collections. In 1932, it was integrated into the Department of Asian Arts, which had just been created and which was directed by Georges Salles (Bresc-Bautier, Fokenell, and Mardrus, 2016, p. 457). It was then transferred to the Musée Guimet in 1945, on the initiative of the museum’s curator, who assembled the national Asian collections there (Bresc-Bautier, Fokenell, and Mardrus, 2016, p. 459).

The collector’s approach and aims

It is still difficult today to precisely ascertain the total number of items in Ernest Grandidier’s collections. The 1894 donation mentioned 3,135 Chinese objects, with the addition of almost 800 Japanese ceramic wares in 1895, as well as successive additions to the collection made by the collector until 1912. According to Jean-François Jarrige, Grandidier collected a total of almost 8,000 objects (Les Donators du Louvre, 1989, p. 108). This number means that his collection of Chinese porcelain was the largest in France. The collection was also remarkable due to the quality of the objects, and it included porcelain pieces with rare decorations and techniques.

The two collections—Chinese and Japanese—comprised a great many forms, types of decoration, sizes, and periods. The collector ceased to collect Japanese ceramics in 1899 (Chopard, 2020, p. 3), and some of these items were sent to the Musée de la Céramique in Rouen in 1900. The remaining collection was still as impressive as those of other Parisian collections. Grandidier bought pieces that he identified as coming from ‘Kioto’ (this appellation encompassed very diverse provenances at the time), Hizen province, Imari, and Satsuma. This matched the general tendencies of the Parisian collectors and dealers of Japanese ceramics from this period, in particular Siegfried Bing (Gonse L., 1900, pp. 306, 308, and 312). The latter was one of the main suppliers of Japanese ceramic wares, along with Antoine de La Narde (1839–19?).

Grandidier mainly focused on collecting Chinese porcelain, and in the year he made his first donation he published a book entitled La Céramique chinoise. In the introduction, he stated that he wished to write about the history of Chinese porcelain (Grandidier, E., 1894, p. 6), which he illustrated with items from his collection. Reproduced by rotogravure, they were inserted as plates at the end of the book. The latter was in line with the studies published in the middle of the nineteenth century on the history of Chinese porcelain (d’Abrigeon, P., 2018, Chang, W.-C., 2008, and Chopard, L., 2018a).

The tone adopted by Grandidier in his writing was intended to be persuasive: he considered Chinese porcelain superior to other Western and Eastern ceramics (Grandidier, E., 1894, p. 4). His collection is also a useful ensemble, both due to its role in the study of porcelain per se and its inspiration for French industry (Grandidier, 1894, pp. 5–6).

The polychrome pieces, which he primarily defended in his work (Grandidier, E., 1894, p. 73), represented the vast majority of the collected pieces. The monochrome items were less present, although the collector did collect several series of flamed, turquoise, and blanc de Chine objects. Grandidier mainly acquired porcelains from the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), notably dating from the reigns of Kangxi (1662–1722) and Qianlong (1735–1796). He also bought several hundred objects dating from the Ming Dynasty and just over one hundred from the Song (960–1279) and Yuan (1279–1368) Dynasties (Chopard, L., 2020, p. 3). Grandidier stuck to these major orientations throughout the compilation of his collection. Hence, he regularly collected objects from the Song, Yuan, Ming (1368–1644), and Qing Dynasties, without prioritising one or other of these periods throughout his life. He also acquired a terracotta object that he dated to the Han Dynasty (inventory no. G5604), which is curiously a one-off item in the ensemble.

The current view of the collections

Although Ernest Grandidier set out to collect only Chinese porcelain, he did occasionally buy stoneware and terracotta pieces, deliberately or not (Grandidier, 1894, p. 134). A current view of the ensemble primarily highlights variations between the dating and the identifications suggested by the collector and those now commonly accepted as accurate. For example, the first piece inventoried (inventory no. G1) is identified as being a stoneware bottle with slip decorations from the Yuan Dynasty. It was, however, bought as a Korean piece before being attributed to Japan by the collector. Likewise, a vase with dragon-shaped handles, which has now been dated to the seventh century (inventory no. G5002; Besse, X., 2004, pp. 32–33), was dated to the Song Dynasty when it was bought in 1902.

Although the collector focused on porcelain from the Qing Dynasty, certain old pieces are highly remarkable. A small coffee pot with phoenix heads (inventory no. G5119) is remarkable by its very high quality. This is made from carved stoneware with a translucent green glaze, and came from the kilns of Yaozhou 耀州, and is now dated from the end of the period of the Five Dynasties (907–979) (Zhou Zhengxi, 2017). According to Grandidier, this piece dated from the reign of Kangxi.

Another exceptional piece is worthy of mention: a meiping vase 梅瓶 from the Yuan Dynasty (inventory no. G1211), which Grandidier dated from the Ming Dynasty (Chopard L., Deléry C., and Gardellin R., 2021). Its cobalt blue decorations feature a white dragon, left in reserve. Very few pieces with these kinds of decorations, whose technique is exceptional, have been found to date (Besse, 2004, pp. 48–49; Chopard L., Deléry C., and Gardellin R., 2021). The presence of these ancient ceramic wares in the collection is noteworthy, because the ‘archaic’ pieces—as they were called at the time—were rare in French collections in the second half of the nineteenth century. However, it is worth noting that the collector dated them to later dynasties. It was not until the 1920s and ‘30s that there was an increase in interest in these ceramic objects, which became more common in France, as did the knowledge about them. With the regard to the Qing pieces, Grandidier collected many series of polychrome enamelled objects, including one of the imperial bowls (for example, inventory nos. G913 and G2890; Besse, 2004, pp. 126–127), and an imposing fifty-centimetre-high jar with a ‘thousand flower’ design (inventory no. G3344). The technical quality of this rich design, comprising a multitude of coloured flowers, is once again remarkable. The application of the enamels created subtle tonal gradations and different thicknesses that increased the definition of each species (Besse, X., 2004, pp. 138–139). Grandidier presented this piece as one of the most important objects in his collection when he first acquired it, and reproduced it in his book, in which it is presented on Plate XXXVI. He also inserted a rotogravure of a white statuette of the Guanyin bodhisattva (inventory no. G535), made from Dehua porcelain 德華, dating from the Kangxi period (Grandidier, E., 1894, pl. X). The quality of the sculpture and the glaze on this object are remarkable, as is the subtlety of the pose.

The Japanese collection was entirely assembled several years ago, as the objects placed in the Musée de la Céramique in Rouen joined the rest of the collection in the Musée National des Arts Asiatiques - Guimet. Rarely published, the Japanese pieces collected by Ernest Grandidier form a high-quality ensemble, originating from the many kilns on the Japanese archipelago. It is now believed that the collected objets were produced between the beginning of the seventeenth and end of the nineteenth century.

The extent of Ernest Grandidier’s donation to the Louvre made him one of the most important donators to French public collections. The extent of his collection, his generosity, and devotion were echoed by his contemporaries. Raymond Kœchlin devoted part of his text to him; this was read out at the general assembly of the Société des Amis du Louvre on 16 January 1914, which paid tribute to the donators of the museum’s Far-Eastern collections. During his speech, he declared that Grandidier was ‘certainly the most generous donator to our Far-Eastern museum, and thanks to him the art of Chinese porcelain produced over the last centuries is represented in all its profusion by magnificent examples’ (Kœchlin, R., 1914, p. 13).

Related articles

Collection / collection d'une personne

Personne / personne