Anquetil-Duperron, Abraham Hyacinthe

Rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin

Ancien 397 rue du Mont-Blanc.

57 rue des Blancs-Manteaux

Chez Guillaume-Louis Anquetil.

Interprète pour les langues orientales.

Bibliothèque du roi

Biographie

La biographie d’Anquetil-Duperron est connue par la description détaillée qu’il donne de son voyage en Inde dans un discours préliminaire publié en introduction à sa traduction du Zend Avesta (Paris, 1771). Ce texte indépendant a d’ailleurs fait l’objet d’une édition scientifique par Jean Deloche, Manonmani Filliozat et Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997). Des notices nécrologiques (Anquetil L. P., 1805, Dacier J. B., 1808) et des ouvrages inspirés par la figure de ce pionnier (Brunnhoffer H., 1883 ; Menant D., 1907 ; Modi J. J., 1916 ; Schwab R., 1934 ; Kieffer J.-L., 1983 ; Filliozat P. S., 2005) complètent les sources permettant de tracer ici les grandes lignes de sa biographie.

Formation

Né à Paris le 7 décembre 1731, Anquetil-Duperron fit ses études à l’université de Paris et dans les milieux jansénistes. Lecteur assidu de la Bibliothèque du roi à Paris, intéressé par les langues orientales, notamment l’hébreu, il est remarqué par l’abbé Claude Sallier (1685-1761), garde du département des Imprimés, qui l’introduit auprès des milieux savants (Filliozat P. S., 2005, p. 1262). La légende veut que sa vocation d’orientaliste naisse lorsque Michel-Ange-André Leroux-Deshauterayes (1724-1795), professeur d’arabe au Collège de France, lui montre le calque de quatre feuillets d’un manuscrit en vieux-perse conservé à Oxford (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 75). Cet événement le décide à se rendre en Inde pour apprendre les langues, chercher des manuscrits et traduire les textes permettant de comprendre la civilisation indo-iranienne encore mal connue en Europe.

Voyage en Inde

Sans attendre de mission scientifique officielle, il s’engage dans l’armée de la Compagnie des Indes et quitte Paris le 7 novembre 1754. Arrivé à Lorient, il est nommé interprète pour les langues orientales à la Bibliothèque du roi, doté d’une pension et d’une place sur le Duc d’Aquitaine qui part pour l’Inde le 24 février 1755 (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 77-79). Anquetil-Duperron arrive à Pondichéry le 9 août 1755 et cherche tout de suite à apprendre les langues indiennes, notamment le sanskrit (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 89). Pour ce faire, il part à Chandernagor au Bengale, où son état de santé, déjà affaibli par des maladies, se détériore. Au printemps 1757, il est empêché par la guerre de Sept Ans de se rendre à Bénarès pour étudier le sanskrit et assiste à la prise de Chandernagor par les Anglais. Il retourne à Pondichéry par voie de terre, après un long voyage rocambolesque, où il retrouve son frère, Étienne Anquetil de Briancourt (1727-1793) (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 95-163). Ils partent tous les deux pour Surat au Gujarat, via Mahé, Goa et Aurangabad où Anquetil-Duperron rencontre Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Gentil (1726-1799) avec qui il noue une amitié portée par une curiosité scientifique commune (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 271). Arrivé le 1er mai 1758 à Surat, il assiste de nouveau à la prise de la ville par les Anglais. L’année suivante, il rencontre les destours parsis Darab et Kaous, avec qui il étudie la riche littérature zoroastrienne en vieux-perse (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 339 et passim). En 1761, la domination anglaise l’oblige à rentrer en France. Le 15 mars 1761, il quitte Surat et l’Inde via Bombay, sur un navire de prisonniers français (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 436). Une fois libéré, il profite de sa présence en Angleterre pour examiner les manuscrits avestiques de la bibliothèque d’Oxford et rencontrer les professeurs de l’université.

Retour à Paris

Rentré à Paris le 14 mars 1762, Anquetil-Duperron dépose le lendemain dix-huit manuscrits à la Bibliothèque du roi (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 461) où il reste, engagé comme interprète pour les langues orientales jusqu’en 1792. Le 6 septembre 1763, il est élu membre de l’Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres où il siège jusqu’à sa réorganisation par Napoléon, à qui il refuse de prêter serment de fidélité, lequel, pour lui, « n’est dû qu’à Dieu, par la créature au Créateur » (AN A/A/63 ; Schwab R., 1934 ; Filliozat P. S., 2005, p. 1279). Il meurt chez son frère Guillaume-Louis Anquetil (1735-?) le 18 janvier 1805 (28 nivôse an XIII), après avoir mené une vie centrée sur son travail scientifique, privée des plaisirs du monde, se comparant à un « renonçant des bords de la Seine » (Filliozat P. S., 2005, p. 1274).

Article rédigé par Jérôme Petit

Biography

Anquetil-Duperron's biography is known through his detailed description of his trip to India in a speech published as an introduction to his translation of the Zend Avesta (Paris, 1771). Furthermore, this text was the subject of a scientific publication by Jean Deloche, Manonmani Filliozat, and Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997). Obituaries of (Anquetil L. P., 1805, Dacier J. B., 1808) and works inspired by this pioneer (Brunnhoffer H., 1883; Menant D., 1907; Modi J. J., 1916; Schwab R., 1934; Kieffer J .-L., 1983; Filliozat P. S., 2005) provide further sources that make it possible to retrace the main threads of his life.

Training

Born in Paris on December 7, 1731, Anquetil-Duperron studied at the Université de Paris and in Jansenist circles. As a diligent reader at the Bibliothèque du roi in Paris who was interested in eastern languages, especially Hebrew, he was noticed by Abbé Claude Sallier (1685-1761), custodian of the département des Imprimés, who introduced him into scholarly circles (Filliozat P.S., 2005, p. 1262). Legend has it that his vocation as an orientalist was born when Michel-Ange-André Leroux-Deshauterayes (1724-1795), professor of Arabic at the Collège de France, showed him the tracing of four leaves of a preserved Old Persian manuscript in Oxford (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 75). This event persuaded him to go to India to learn languages, search for manuscripts, and translate texts to understand the Indo-Iranian civilisation still little known in Europe.

Travel to India

Without waiting for an official scientific mission, he enlisted in the army of the Compagnie des Indes and left Paris on November 7, 1754. After arriving in Lorient in Brittany, he was appointed interpreter for oriental languages at the Bibliothèque du roi and was given a pension and a place on the Duc d’Aquitaine, which left for India on February 24, 1755 (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 77-79). Anquetil-Duperron arrived in Pondicherry on August 9, 1755 and immediately launched upon his quest to learn Indian languages, particularly Sanskrit (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 89). To this end he traveled to Chandernagor in Bengal, where his state of health, already weakened by illnesses, deteriorated. In the spring of 1757, he was prevented by the Seven Years' War from going to Benares to study Sanskrit and witnessed the capture of Chandernagor by the English. He returned to Pondicherry by land, after a long, incredible journey, during which he encountered his brother, Étienne Anquetil de Briancourt (1727-1793) (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 95-163). They both left for Surat in Gujarat, via Mahé, Goa, and Aurangabad, where Anquetil-Duperron met Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Gentil (1726-1799), with whom he formed a friendship driven by shared scientific curiosity (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 271). After arriving on May 1, 1758 in Surat, he again witnessed a city’s capture by the English. The following year, he met the Parsi destours Darab and Kaous, with whom he studied the rich Zoroastrian literature in Old Persian (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 339 et passim). In 1761, English domination forced him to return to France. On March 15, 1761, he left Surat and India via Bombay, on a French prisoner ship (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 436). Once released, he took advantage of his presence in England to examine the Avestan manuscripts of the Oxford library and meet the professors of the university.

Back to Paris

After arriving back in Paris on March 14, 1762, Anquetil-Duperron deposited eighteen manuscripts at the Bibliothèque du roi the very next day (Anquetil-Duperron A. H., 1997, p. 461) where he would remain employed as an interpreter for Oriental languages until 1792. On September 6, 1763, he was elected a member of the Academy des inscriptions et belles-lettres where he remained until its reorganisation by Napoleon, to whom he refused to take the oath of loyalty, which, for him, was "owed only to God, from the creature to the Creator" (AN A/A/63; Schwab R., 1934; Filliozat P. S., 2005, p. 1279). He died at the home of his brother Guillaume-Louis Anquetil (1735-?) on January 18, 1805 (28 Nivôse, year XIII), having led a life centred upon his scientific work, deprived of the pleasures of the world, likening himself to a "renunciant on the banks of the Seine” (Filliozat P.S., 2005, p. 1274).

Article by Jérôme Petit (Translated by Jennifer Donnelly)

[Objets collectionnés] 18 manuscrits avestiques, 2 manuscrits en turc, 7 manuscrits en arabe, 7 manuscrits en pehlevi, 80 manuscrits en persan, 3 manuscrits en ourdou, 1 manuscrit en kannada, 2 manuscrits en malayalam, 4 manuscrits en tamoul, 6 manuscrits en sanskrit.

Un premier dépôt

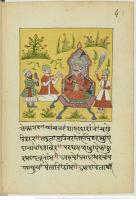

La collection des manuscrits d’Anquetil-Duperron est arrivée en deux temps à la Bibliothèque nationale. Anquetil-Duperron a déposé lui-même dix-huit manuscrits dès son retour à Paris, le 15 mars 1762. Il décrit lui-même ces collections dans le second volume de sa traduction du Zend Avesta (vol. II, p. I-XL ; Anquetil-Duperron, 1997, p. 461). Il s’agit essentiellement de manuscrits mazdéens en vieux-perse et en pehlvi, versés dans le fonds « Persan » (BnF Supplément Persan 26, 27, 29, 32, 33, 34, 39, 40, 43), de manuscrits persans (BnF Supplément Persan 37, 41, 42, 46, 47, 48, 417, 983) et d’une traduction en gujarati de l’Ardā Vīrāf Nāmag (BnF Indien 722), un conte en moyen-perse relatant le voyage de l’âme d’Ardā Vīrāf qui parcourt les paradis et les enfers décrits par Zoroastre. Ce volume présente une centaine de peintures, souvent en pleine page, dans le plus beau style de l’école gujarati.

Le testament

Quelques jours avant sa mort, Anquetil-Duperron rédige son testament et désigne Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy (1758-1838) comme légataire de ses manuscrits, comportant à la fois ses papiers scientifiques et ses manuscrits indiens : « Je donne et lègue à M. de Sacy mon ancien confrère à l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, tous les manuscrits écrits de ma main et d’autres mains contenant mes travaux sur les matières orientales, formant plus de sept à huit volumes in folio et in quarto et autres formats, ensemble les cartes générales et particulières grand et petit atlas, manuscrits et imprimés ou gravés qui y tiennent ou en font partie. Je veux et entends que tous les manuscrits orientaux écrits dans les différentes langues du pays que je possède soient remis au même M. de Sacy pour en disposer par lui ainsi qu’il avisera, à la charge pour lui d’en régler la valeur et d’en payer le montant à mes frères » (Institut, NS 375, no 47 ; cité par Dehérain H., 1919, p. 155).

L’acquisition de la collection par la Bibliothèque nationale

Sacy dresse un inventaire des collections de manuscrits orientaux (Institut, NS 375, no 46, repris dans BnF, NAF 5433, p. 21-36) et en propose l’acquisition à la Bibliothèque impériale. La collection est évaluée par les conservateurs lors de la séance du Conservatoire de la Bibliothèque impériale du 28 mars 1805 (7 germinal an XIII) : « Les conservateurs des Manuscrits annoncent au Conservatoire qu’ils ont examiné avec soin les manuscrits orientaux de feu M. Anquetil du Perron et que d’après une évaluation faite concurremment avec M. Silvestre de Sacy chargé des intérêts de la famille Anquetil, le prix de cette collection monte à la somme de 6 690 francs. Les conservateurs des Manuscrits propose[nt] de réduire cette somme à celle de six mille francs, et de faire cette offre à M. de Sacy. Le Conservatoire approuve leur proposition et les autorise à faire les démarches nécessaire[s] pour terminer cette acquisition. » (BnF, Archives modernes 55-56, p. 3). La remise des manuscrits est enregistrée lors de la séance du 2 mai 1805 (12 floréal an XIII) : « Les conservateurs des Manuscrits annoncent que les manuscrits orientaux de M. Anquetil du Perron, au nombre de cent cinquante-six, leur ont été apportés ce matin » (BnF, Archives modernes 55-56, p. 5). Ces deux procès-verbaux sont signés de Pascal-François-Joseph Gossellin (1751-1830), géographe, président du Conservatoire de la Bibliothèque, et Louis Langlès (1763-1824), conservateur en charge des Manuscrits orientaux.

Les papiers scientifiques

Sa collection de livres imprimés, largement annotés de sa main et « maltraités par les vers » selon les mots de Sacy (Institut, NS 375, no 716 ; cité par Dehérain H., 1919, p. 137), fut mise en vente et dispersée. Les 25 volumes de ses papiers scientifiques furent donc acquis par la Bibliothèque avec le lot de manuscrits. Ils forment actuellement le « fonds Anquetil-Duperron » des Nouvelles Acquisitions françaises (BnF, NAF 8857-8882). Ce fonds contient notamment sa traduction française des Upaniṣad (« Oupnek’hat, traduit littéralement du persan, mêlé de samskrétam [1786] », BnF NAF 8857) qu’il publiera finalement en latin (Oupnek’hat, id est, Secretum tegendum continens doctrinam e quatuor sacris Indorum libris excerptam, Strasbourg, 1801-1802). On y trouve aussi les brouillons de sa traduction de l’Avesta, des études sur différents textes mazdéens, des notes sur les Parsis, des lexiques du persan et du sanskrit d’après les textes originaux, ainsi qu’une riche correspondance avec les savants de son temps, notamment le père jésuite Gaston-Laurent Coeurdoux (1691-1779) qu’il avait rencontré en Inde et qui joua un rôle important dans sa collecte de manuscrits et son apprentissage de la langue et de littérature sanskrites.

Les manuscrits orientaux

Les manuscrits orientaux acquis par la Bibliothèque nationale ont été d’abord décrits par Anquetil-Duperron en annexe à son introduction au Zend Avesta (voir Voyage en Inde, 1997, p. 482-494). Ils se composent de 2 manuscrits en turc, 7 en arabe, 7 en ancien persan, 80 en persan moderne, 3 en hindoustani (ourdou), 1 en kanada, 2 en malayalam, 4 en tamoul et 6 en sanskrit. Ils furent ensuite décrits par Sacy comme 12 « manuscrits zends, pehlevis, persans et indiens relatifs à la religion ou à l’histoire des Parsis ou disciples de Zoroastre », 16 « manuscrits en sanscrit et autres langues indiennes », 9 « manuscrits arabes », 90 « manuscrits persans », 2 « manuscrits turks », 1 « manuscrit français » (« Description de la Haute Éthiopie, de Pétis de la Croix », BnF NAF 1822). Sacy ajoute à sa liste les dix-huit manuscrits déposés par Anquetil-Duperron à son retour de l’Inde ainsi qu’une liste des « brouillons d’Anquetil » (voir BnF NAF 5433, p. 21-36). Parmi ces manuscrits, on trouve un nombre important de manuscrits persans dont certains présentent des peintures, comme le Barzū-Nāma d’Atā’i Rāzī contenant des peintures exécutées à Surat en 1760 (BnF Supplément Persan 499 et 499 A) ou l’Anvār-i Suhaylī, traduction persane du recueil de contes arabes, le Kalila wa Dimna, comportant douze peintures réalisées en 1713 sous le règne de l’empereur moghol Farruḫ-siyyar (BnF Supplément Persan 920), ou encore un second exemplaire de l’Ardā Vīrāf Nāmag d’une exécution de moindre qualité (BnF Indien 721). On note aussi la présence du manuscrit du Sirr-i Akbar, traduction persane des Upaniṣad commanditée par le prince Dārā Šukūh, à partir duquel Anquetil-Duperron réalisa sa traduction (BnF Supplément Persan 14). Cette copie fut acquise par l’intermédiaire de Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Gentil (1726-1799), autre grand collectionneur de manuscrits indiens.

Article rédigé par Jérôme Petit

An Initial Deposit

The collection of Anquetil-Duperron manuscripts arrived at the Bibliothèque nationale in two instalments. On his return to Paris on March 15, 1762, Anquetil-Duperron himself deposited eighteen manuscripts, which he described in the second volume of his translation of the Zend Avesta (vol. II, p. I-XL Anquetil-Duperron, 1997, p. 461). These were essentially Mazdean manuscripts in Old Persian and Pehlvi, transferred to the "Persan" collection (BnF Supplément Persan 26, 27, 29, 32, 33, 34, 39, 40, 43), Persian manuscripts (BnF Supplément Persian 37, 41, 42, 46, 47, 48, 417, 983), and a Gujarati translation of the Ardā Vīrāf Nāmag (BnF Indien 722), a Middle Persian tale relating the journey of the soul of Ardā Vīrāf who traverses the paradises and the hells described by Zoroaster. This volume presents a hundred paintings, often full-page, in the most beautiful style of the Gujarati school.

The Will

A few days before his death, Anquetil-Duperron wrote his will and designated Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy (1758-1838) as legatee of his manuscripts, including his scientific papers and his Indian manuscripts: "I give and bequeath to M. de Sacy, my former colleague at the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, all the manuscripts written by my hand and by others containing my works on Oriental matters, forming more than seven to eight volumes in folio and in quarto and in other formats, together with the general and particular maps and large and small atlases, the manuscripts and printings or engravings which are included in or form part of them. I wish and intend that all the oriental manuscripts written in the different languages of the country that I possess be given to the same M. de Sacy to dispose of them by him as he will advise, on condition that he evaluate their worth and pay the amount to my brothers” (Institut, NS 375, no. 47; quoted by Dehérain H., 1919, p. 155).

The Acquisition of the Collection by the Bibliothèque nationale

Sacy drew up an inventory of the collections of oriental manuscripts (Institut, NS 375, no 46, included in BnF, NAF 5433, p. 21-36) and proposed their acquisition to the Bibliothèque impériale. The collection was evaluated by the curators during the meeting of the Conservatoire de la Bibliothèque impériale on March 28, 1805 (7 germinal year XIII): “The curators of the manuscripts announce to the conservatory that they have carefully examined the oriental manuscripts of the late M. Anquetil du Perron and that according to an evaluation made concurrently with M. Silvestre de Sacy, in charge of the interests of the Anquetil family, the price of this collection reaches the sum of 6,690 francs. The curators of the manuscripts propose to reduce this sum to 6,000 francs, and to make this offer to M. de Sacy. The conservatory approves their proposal and authorises them to take the necessary steps to complete this acquisition” (BNF, Archives modernes 55-56, p. 3). The delivery of the manuscripts was recorded during the session of May 2, 1805 (12 Floréal, Year XIII): "The curators of the manuscripts announce that the Oriental manuscripts of M. Anquetil du Perron, numbering one hundred and fifty-six, have been brought to them this morning” (BNF, Modern Archives 55-56, p. 5). These two minutes are signed by Pascal-François-Joseph Gossellin (1751-1830), geographer, president of the Conservatoire de la Bibliothèque, and Louis Langlès (1763-1824), curator responsible for Oriental Manuscripts.

Scientific Papers

His collection of printed books that was extensively annotated in his own hand and "mistreated by the worms", in the words of Sacy (Institut, NS 375, no 716; quoted by Dehérain H., 1919, p. 137), was put up for sale and scattered. The 25 volumes of his scientific papers were therefore acquired by the library with the batch of manuscripts. They currently form the "Anquetil-Duperron fund" of the Nouvelles Acquisitions françaises (BnF, NAF 8857-8882). This collection in particular contains his French translation of the Upanishads ("Oupnek'hat, literally translated from Persian, mixed with samskrétam [1786]", BnF NAF 8857) which he would finally publish in Latin (Oupnek'hat, id est, Secretum tegendum continens doctrinam e quartet sacris Indorum libris excerptam, Strasbourg, 1801-1802). There are also drafts of his translation of the Avesta, studies on various Mazdean texts, notes on the Parsis, lexicons of Persian and Sanskrit based on the original texts, as well as a rich correspondence with scholars of his time, notably the Jesuit Father Gaston-Laurent Coeurdoux (1691-1779) whom he had met in India and who played an important role in his collection of manuscripts and his learning of the Sanskrit language and literature.

Oriental Manuscripts

The Oriental manuscripts acquired by the Bibliothèque nationale were first described by Anquetil-Duperron in an appendix to his introduction to the Zend Avesta (see Voyage en Inde, 1997, p. 482-494). They consist of two manuscripts in Turkish, seven in Arabic, seven in Old Persian, 80 in Modern Persian, three in Hindustani (Urdu), one in Kanada, two in Malayalam, four in Tamil, and six in Sanskrit. They were further described by Sacy as twelve "Zend, Pehlevis, Persian, and Indian manuscripts relating to the religion or history of the Parsis or followers of Zoroaster", sixteen "manuscripts in Sanskrit and other Indian languages", nine "Arabic manuscripts", 90 “Persian manuscripts”, two “Turkish manuscripts”, and one “French manuscript” (“Description de la Haute Éthiopie, de Pétis de la Croix”, BnF NAF 1822).

Sacy added to his list the 18 manuscripts deposited by Anquetil-Duperron on his return from India as well as a list of "Anquetil's drafts" (see BnF NAF 5433, p. 21-36). Among these manuscripts, we find a large number of Persian manuscripts, some of which present paintings, such as the Barzū-Nāma of Atā'i Rāzī containing paintings made in Surat in 1760 (BnF Supplement Persan 499 and 499 A) or the Anvār -i Suhaylī, a Persian translation of the collection of Arabic tales, the Kalila wa Dimna, comprising twelve paintings produced in 1713 during the reign of the Mughal emperor Farruḫ-siyyar (BnF Supplément Persan 920), or a second copy of the Ardā Vīrāf Nāmag of lesser-quality execution (BnF Indien 721). We also note the presence of the manuscript of Sirr-i Akbar, a Persian translation of the Upanishads commissioned by Prince Dārā Šukūh, from which Anquetil-Duperron made his translation (BnF Supplement Persan 14). This copy was acquired through Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Gentil (1726-1799), another major collector of Indian manuscripts.

Article by Jérôme Petit (Translated by Jennifer Donnelly)